Earth’s orbit is littered with debris dating from the beginnings of the conquest of space. So that it can still be accessible, efforts are being made to deorbit satellites at the end of their life. But there is also the task of treating all the objects whose design has not planned for the future.

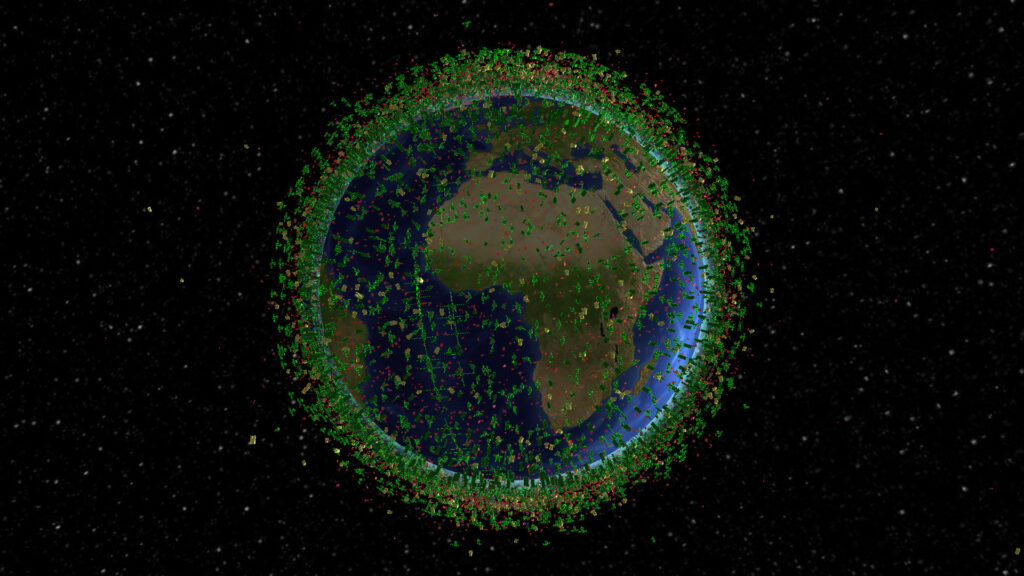

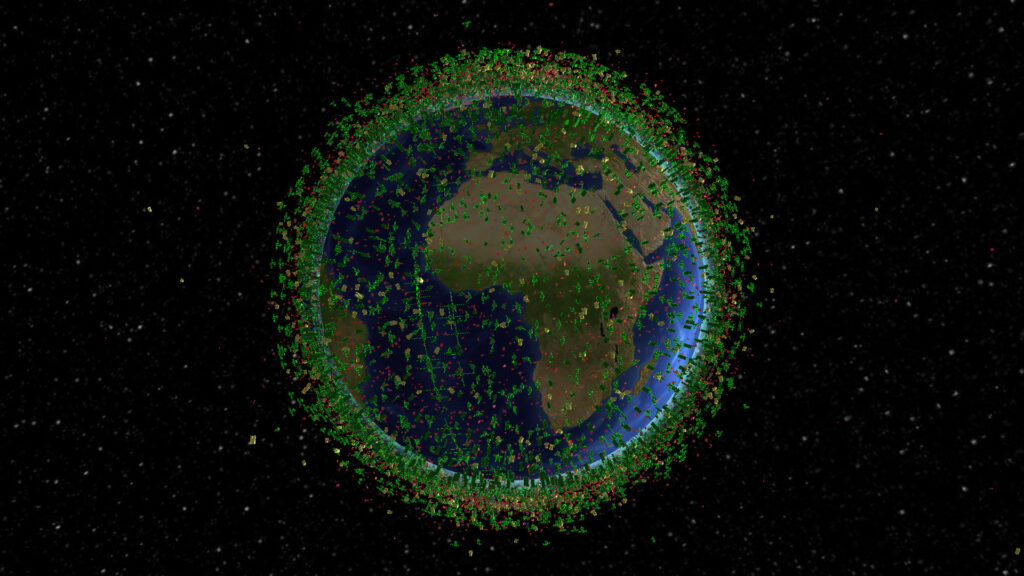

The increase in space traffic, particularly due to the arrival of new private players and the democratization of space technologies, results in an exponential increase in the number of objects in orbit. This situation will pose serious security problems if it is not quickly taken into account.

The main danger lies in collisions between satellites and space debris. They occur at very high speeds (between 7 and 16 km/s) and the collision of a single object can generate a multitude of additional debris, creating a domino effect and worsening the problem. This process is called Kessler syndrome, after the American NASA scientist who first alerted to this problem in 1978.

Currently, we can only observe objects in orbit larger than 10 cm from the ground. There are approximately 35,000 objects larger than this size in orbit, of which 9,000 are active satellites with 5,200 Starlink satellites and 600 OneWeb satellites. The number of space debris larger than 1 mm is estimated at around 128 million. The risk of collision is particularly high in certain areas, such as low Earth orbit, where most satellites are concentrated.

Deorbiting satellites, key preventative measure

France has established itself as one of the pioneers in the fight against the proliferation of space debris. Indeed, from 2008, the law relating to space operations laid the foundations for a proactive approach, requiring French operators to respect a certain number of rules to limit their environmental impact.

To prevent the creation of new debris, it is, for example, essential to deorbit satellites at the end of their life. This operation, complex and expensive, requires reserving part of the satellite’s energy to propel it into the Earth’s atmosphere so that it disintegrates thanks to air friction.

Many satellites launched in the early years of the space age have unfortunately not been de-orbited and today constitute “swords of Damocles” in orbit, increasing the risk of collisions and constituting a reserve of small, untraceable debris in the event of of fragmentation.

How to capture and remove debris in space?

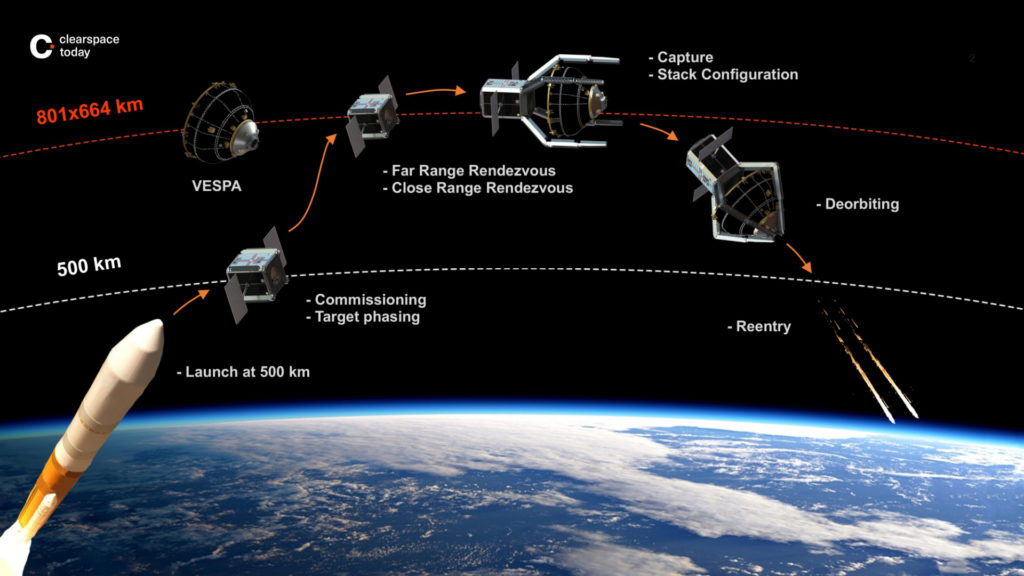

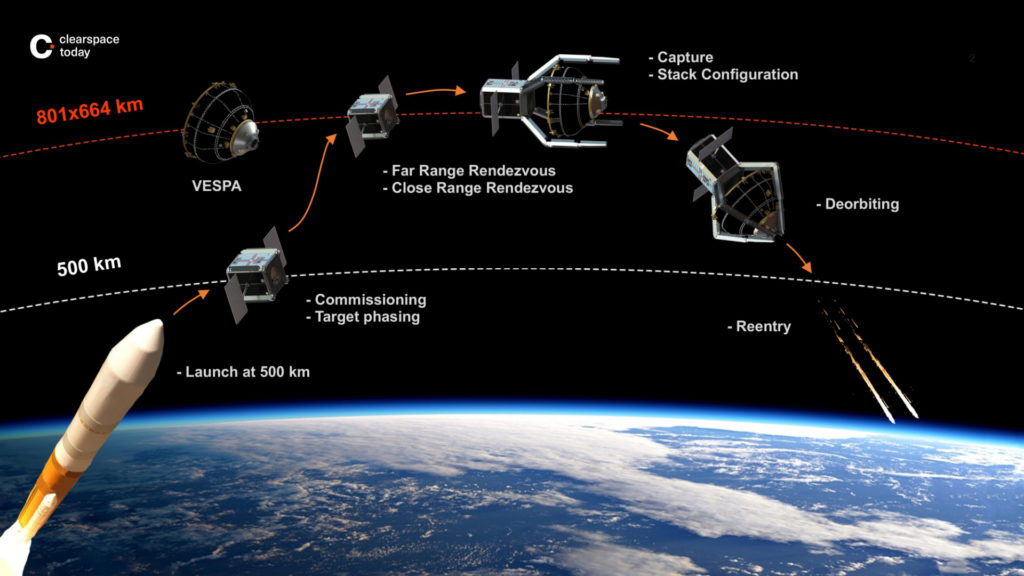

Start-ups and companies, particularly in France, are working on technological building blocks to get closer to this debris, to synchronize their trajectory with that of the vehicle picking them up, to catch them and finally to deorbit them. The operation is complex and expensive.

Today there are some projects toactive debris removal (ADR) in progress. We can cite the ClearSpace-1 project of the European Space Agency (ESA) which aims to deorbit in 2026 a piece of the 112 kg stage of the Vega launcher. The Japanese company Astroscale has also been developing ADR activities since 2013, with a number of in-orbit demonstrations already carried out. Its ADRAS-J mission, launched on February 18, aims to get closer to a third stage of Japanese H-2A launchers put into orbit in 2009, and to synchronize with this stage to validate the final rapprochement phase. Astroscale has recently set up an office in France to develop part of its activities also in France. The Bordeaux start-up Dark is also positioning itself on debris interception with innovative solutions.

The activity is booming, but needs a commercial anchor in order to really “take off”. Today, only States finance this theme. It is therefore not yet profitable from an economic point of view to collect debris. To resolve this dilemma, we should be able to give value to debris by promoting their recycling and reuse. We could also try to estimate the economic cost of a collision and the large quantity of debris generated which will disrupt space operations. This loss of income triggered by inaction must be weighed against the cost of the cleaning intervention. But it is very difficult today to estimate and construct these economic models.

To remedy this problem, the idea of a troubleshooting, towing and repair service for satellites in orbit, and capable of capturing space debris, is being considered. This system would be based around multifunctional spacecraft. In addition to repairing broken satellites, these craft would capture debris at the end of their repair missions, returning it to Earth’s atmosphere to disintegrate. This economic model has the advantage of generating income, thanks to the repair service and the potential recovery of materials recovered from debris.

An economic model to be created based on regulations

Regulation can help this economic model. The strict rule requiring that all objects placed in orbit must be de-orbited at the end of their life with a probability of 100% effectively requires “systems” to be available to pick up broken down vehicles. The analogy with roadside assistance packages is not far off.

It would then become cheaper to pay a breakdown service to come and recover a broken down vehicle rather than having the recovery capacity yourself. This can promote a virtuous economy which cleans objects recently put into orbit, but also recovers objects from historic missions which bother us today.

An effort that needs international cooperation

However, challenges remain. Technological development for capturing and deorbiting space debris is still ongoing. In addition, an international legal framework is necessary to define the responsibilities and obligations of the actors involved. France calls for concerted international action to face this global challenge. Collaboration between nations is essential to develop effective technological and legal solutions and ensure the security of space for future generations.

In conclusion, the establishment of an economic model for space depollution is a crucial issue to guarantee the security and sustainability of space exploration. Although there are challenges ahead, international collaboration and technological innovation can help overcome them and ensure a sustainable future for space.

Pierre Omaly, Space debris expert and head of the Tech 4 Space Care initiative, National Center for Space Studies (CNES)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Subscribe to Numerama on Google News so you don’t miss any news!