The power of truth has long spoken in order to enforce its will. It’s different in the digitized world.

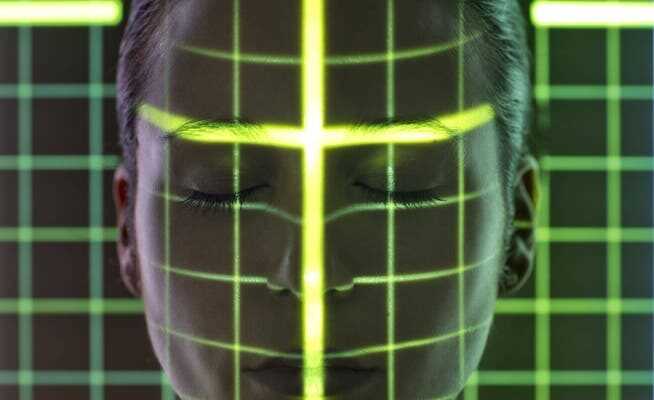

Today, in order to influence people, you don’t need convincing narratives, but correctly configured algorithms.

One of the most literary passages in the New Testament is the scene (John 18:37-38) in which the prisoner Jesus confesses that he came into the world to bear witness to the truth – and Pilate, already going away and without one waiting for an answer, asking him: “What is truth?”

At that moment the Roman seems to be the wise one and the Nazarene to behave like a naïve child who doesn’t know and doesn’t consider so much: Not that there are many and contradictory truths that philosophy was endlessly debating even at that time had. Not that the non-philosophical course of the world gets along quite well without truth (if only there is enough military and administrative correctness, economically negotiated coherence, belief in social values and personal and family honesty). And above all not that truth is at least as much a question of power as a question of knowledge.

Pilate could also have asked in which areas of life there was any talk of truth at all. That would have drawn Jesus’ attention to the fact that truth can only be found in politics, in religion and in court – i.e. in power domains in which truth always also secures power structures. Perhaps then Jesus would have understood that he had unknowingly gotten into a power struggle that would now cost him his life. However, the childlike naivety of Jesus seems to Pilate to be evidence of harmlessness – and so the governor steps before the people and says that he cannot see any guilt in the accused.

However, the text was written by an evangelist who would certainly not have signed this reading. John did not want Jesus to appear naïve. He wanted to say that Christ bears witness to the truth by virtue of his divine authority. But the world does not understand this truth: the scene in which Pilate asks for the truth is an expression of darkness.

At the beginning of the same gospel, Jesus’ light shines into them, and John writes: “The darkness did not understand.” The highlight of this sentence is that “understood” (Greek: “katelaben”) also means “seized”: On the one hand, the darkness did not understand the light of truth, on the other hand it could not get hold of it, could not kill it. Applied to Pilate, this would mean that although he is an agent of darkness, he nevertheless remains receptive to a truth beyond worldly power, a truth of light and enlightenment, for which he half-heartedly tries to save Jesus.

The basic conflict seems yesterday

If you bring both readings together – truth as an instrument of power and truth as divine light – a question of perspective arises. From the point of view of power, enlightenment appears naïve, from the point of view of the divine, truth appears corrupted when it degenerates into a question of power.

The ambivalence of these two perspectives persisted for a long time and rearranged itself from epoch to epoch. While the illuminating light gradually migrated from Christian truth to the truths of Renaissance humanism, the Enlightenment, and scientific advance, Pilate’s followers were never lacking: politicians and thinkers who, like Machiavelli or Nietzsche, believed truth as expression, Consequence and means of power understood. Michel Foucault went so far as to describe the form and substance of truth fundamentally as an effect of power. He argued convincingly that it is always the result of a control over who can speak, how and about what.

However, the present form of this conflict seems idiosyncratically stale. Anyone who still sees truth as a question of power easily feels in the vicinity of conspiracy theories and alternative facts. One rubs one’s eyes in amazement at the Russian propaganda painting tanks with the letter V and urging Russians to follow a “truth” unsupported by any facts.

But why does the truth seem so yesterday? If we also think in terms of power here, this circumstance can perhaps be understood a little better. Max Weber defined power as the “chance within a social relationship to assert one’s own will, even against resistance” – and of course one could use the truth (even if it was a lie) by virtue of persuasion to reduce resistance and thus increase the chance of asserting one’s will .

Predictions replace statements

Today you increase this chance differently. For example, if you think about how apps control our information, our routes, our appointments, how well-calculated incentives influence our behavior as “nudges”, how social networks direct our communication and bring us to our (sometimes supposed, sometimes actual) interests – then one realizes that truth is no longer very important to power. Instead of true statements, today it is about correctly calculated predictions, such as those provided by artificial intelligence. And then it’s a matter of carrying out control interventions that are as micro-invasive as possible.

Nerds and conspiracy theorists may still think of power and truth together. Overall, however, power now largely does without truth. It no longer needs persuasion, it needs hacked citizens whose behavior and decisions can be predicted. And it needs user interfaces behind which the ever-increasing complexity of society disappears.

Parallel to this, the development of the epistemic question of truth, aimed at knowledge and cognition, has taken place in recent decades. During this time, scientific facts have increasingly become a question of the correct application and development of empirical (mostly quantitative) methods, and the execution and control of these methods can be digitized more and more and better from decade to decade, and in some cases automated by artificial intelligence .

The human subject slowly but surely lost its central position in the knowledge business – and the knowledge business itself decoupled itself from the subjective and meaningful knowledge and instead shifted more and more to the objectified facts (for whose objectivity subjectivity and sensual perception are considered to be a hindrance). If truth once consisted of the coupling of facts and meaning and, qua meaning, also had a dimension of enlightenment and revelation, today this aspect in particular seems old-fashioned, ideological and obstructive.

Sense becomes something private

How successful this knowledge, reduced to facts, is, especially in political terms, was shown in the Corona period, when it became noticeably dominant for the first time and statistics and scientific findings dominated the news. Other planetary problems – such as the climate crisis – will hardly be able to be addressed without a similar shift towards objectified predictions and calculations. Opinions and interpretations that once formed political truths will henceforth be immediately dismissed as ideologies. Truth is no longer tied to meaning. It has melted down to the level of scientific facts.

But is that even a problem? Only if you want a meaningful world. Whether you want one or not could be a generational question. Fridays for Future and other youth movements mostly want a better world from a functional and mathematical-rational point of view; instead, the sense of truth seems to the younger generation to be something subjective and private, not political.

Perhaps the biblical scene can therefore be rewritten one day: in the dialogue between an elderly conspiracy theorist and the young system administrator of a functionally optimized smart city. Their question, which was only asked out of historical interest, would then be: “Why do you need truth again?”

Jan Söffner is Professor of Cultural Theory and Cultural Analysis at the Zeppelin University in Friedrichshafen.