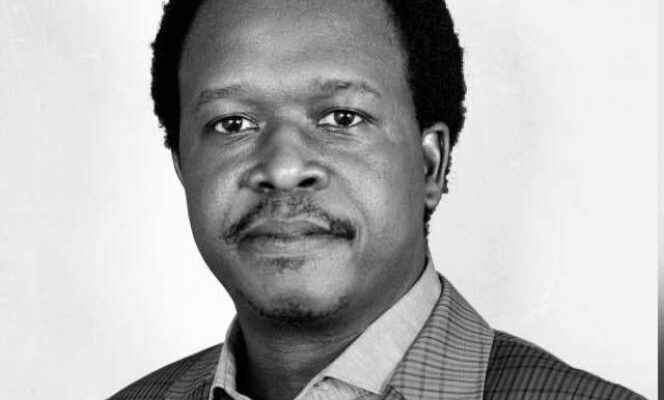

Remadji Hoinathy was born in 1978 in Sarh, in southern Chad. Anthropologist and former professor at the University of N’Djamena, he is now a researcher at the Dakar office of the Institute for Security Studies (ISS).

What is your first memory of contact with France?

My most vivid memory is that of a friendship with two young teachers sent as volunteers to the college where I was in the fourth year, in 1993-1994. Charles-Lwanga College was a Jesuit establishment in Sarh. One taught history-geography and French; the other, mathematics. We had a friendship that went beyond teaching. They spoke to me and my cousin about France as it really is. They came to see us as a family. This was the first direct contact with people from France and living in our conditions.

And your first trip to France?

I hadn’t come directly to France, but to Germany, to enroll in an anthropology thesis. I stayed there for a month and, on my way back, I insisted on changing my ticket to go through Paris. It was no accident. I wanted to see the capital in order to visit all these monuments that I had heard about. But also because, like any young person who grew up in a French-speaking country, I had this romantic image of France. Our history and literature classes bring us back to France, and even when we talk about African literature, it is in Paris that the proponents of Negritude studied and prospered. It was also an opportunity to see an aunt who lives in Argenteuil, in the Paris suburbs, and friends.

In Chad, perhaps a little more than elsewhere, France remains a major political player. How have you seen it evolve over time?

The more we advance in life, the more we understand certain things, and the more we change our perception. Early in my graduate studies, I began to see more clearly the long-standing relationship between France and Chad. These are very winding relationships, with changes of course on the personalities to be supported, but with continuity, that of the defense of French interests and of the men who can guarantee it. It doesn’t matter that it leads to alliance changes. For example, she supported the regime of François Tombalbaye [président de 1960 à 1975] in his fight against various rebellions, before abandoning him. This is also what she did later with Hissène Habré, gradually releasing him in favor of Idriss Déby.

“France here supports a regime that dramatizes democratic life, without ever realizing it”

From Idriss Déby, France’s political agenda has not changed and has focused on stability. Deaf and blind, France doesn’t seem to hear anything else here than maintaining that stability, whatever the cost. One has the impression that the speech of La Baule [prononcé en 1990 par François Mitterrand] on the need for African partners to democratize, was not addressed to Chad. France here supports a regime that dramatizes democratic life, without ever realizing it. However, this does not exclude other forms of relations through cultural, university and academic cooperation, which is not negligible. There are also the projects of the French Development Agency (AFD), which are important for the country. This is the paradox of such an important partner, which invests locally but without a clear agenda in terms of democracy and human rights.

When Emmanuel Macron goes to the funeral of Idriss Déby, in April 2021, do you see this as a mark of loyalty necessary for an ally or as the dubbing of a formula of dynastic succession?

At the symbolic level, this trip was unfortunately catastrophic for the image of France, especially among Chadian youth and part of African public opinion. In the name of good cooperation between the two countries in military operations, it was important for Emmanuel Macron to come to the funeral of such a close partner. It was also important to come and take the pulse of the situation on the spot and to make sure to support the transition so that it goes in the direction of what the Chadians are hoping for.

But this exit was missed because once again Emmanuel Macron came to repeat that stability will be the main agenda and that this requires the maintenance of those who immediately installed themselves in power. [après la mort d’Idriss Déby au combat]. Paris still has the feeling that our country is on the razor’s edge, that it could tip over at any time and that we therefore need regimes and strong men, to the detriment of strong institutions. It would be necessary to go beyond this mechanical conception.

Do you think that after the repression of October 20, which according to an official report left about fifty dead, Paris had the right answer?

The condemnation was not strong enough. I’m not saying that France supports what happened, but, in terms of communication, it has once again been overlooked. When I say “condemnation”, it is not necessarily pointing the finger at anyone, because there have been major slippages by the police and, to a certain extent, by the demonstrators. But the words were not up to what happened and did not emphasize enough the need for the parties to calm the situation, establish responsibilities and return to the negotiating table.

Does France’s policy in Chad, and more broadly on the continent, seem to you today prisoner of its fear of losing its areas of influence?

In Chad, Paris does not defend economic interests, but geostrategic ones. This logic is reinforced as the Russian specter wanders all over Africa. In Chad, it is at the southern gate, in the Central African Republic. The consequence is that this reinforces the more or less blind support for regimes which have understood that it is useful to have jokers in their game. Today, the joker is to threaten to turn to the Russians. This brings us back to some Cold War practices: support me or I rock. Unfortunately, I have the impression that France is too sensitive to this threat.

How would you like to see French policy evolve towards Chad in 2023?

I would say an effort to refocus on questions of democracy and human rights. Supporting stability from a purely military and security point of view, carrying out development projects in the fields of agriculture and health, supporting higher education is not enough to get a country out of the rut or to radiate the image of France as a country of human rights if, among its partners, it is unable to see how democracy works. What is expected is really a movement allowing France not only to be the friend of the regimes which follow one another in Chad, but also the friend of the Chadians as a nation.

Summary of our series “From Dakar to Djibouti, radioscopy of the Africa-France relationship”