Only the flames brought everything to light. On August 4, 2002, a fire broke out above Niederwangen near Bern. There was a fire in the boys’ home “auf der Grube”, which had housed “difficult” boys since 1825. Until then, the public had regarded it as a model home.

An arsonist accuses

But that changed quickly. Shortly after the fire, the arsonist got in touch, called himself “Bubenfreund” and sent a letter of confession to several media. In it he called for the home to be closed and made serious allegations of physical, psychological and sexual violence.

Legend:

Their laughter is deceptive: the pants of the “Gruebe-Buebe”, also known as “sacks”, had to be mended again and again by volunteers. The management didn’t begrudge the children anything else either.

From Luc Spori’s photo album, ca. 1966

As a result, several alumni – the “Gruebe-Buebe” – spoke up. They confirmed that they had experienced violence in the boys’ home for decades, from beatings and psychological pressure to forced labor and abuse.

In focus: the home manager at the time, who led the “pit” from 1966 until his retirement in 2000 with an iron hand, characterized by a military spirit. The presumption of innocence applies to him.

Everyday humiliations

“Everyone hit: the manager, the teacher, the farmer, the carpenter,” remembers Heinz Kräuchi. He was one of the “Gruebe-Buebe”. The now 59-year-old was taken away from his single mother at the age of nine in 1972 as a victim of forced welfare measures. The reason: the mother was overwhelmed with the upbringing.

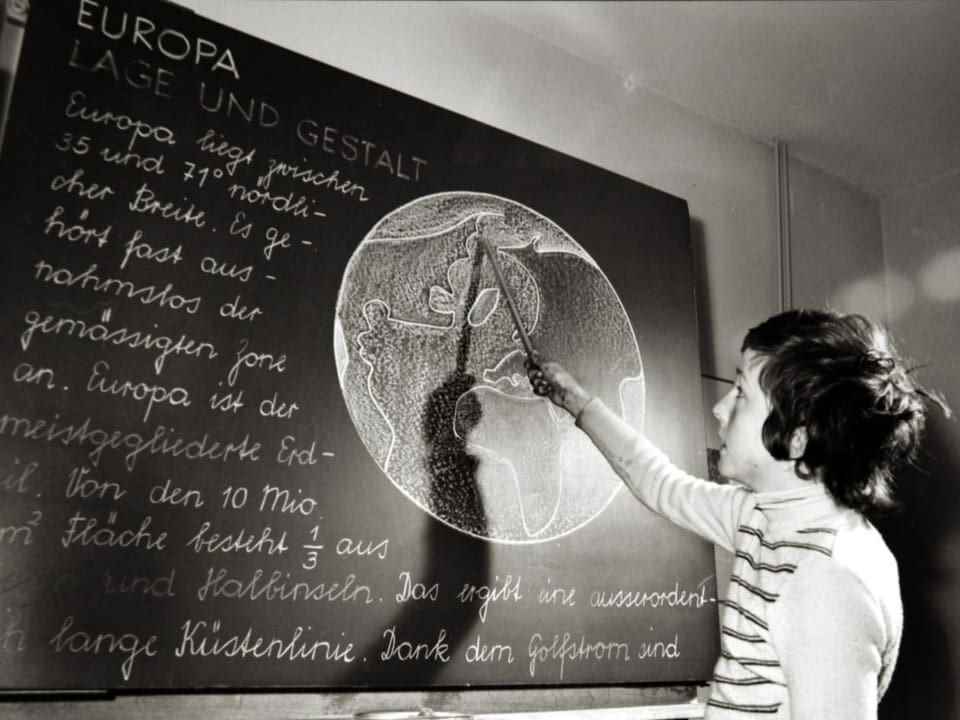

Legend:

Heinz Kräuchi as a boy in the boys’ home: Even if this picture from the 1970s seems harmless, what he experienced back then still haunts him in his sleep.

Heinz Kräuchi

The Bern guardianship authorities took Kräuchi with his older brother to the boys’ home, where he spent seven years from 1972 to 1979. The authorities left his little sister with her mother. So the family was torn apart.

forced to starve

Heinz Kräuchi still dreams of the «pit». Most of all from the dining room, where the director of the home often left him standing in front of the cupboard. If the boy was late for dinner, he had to watch the others eat. Such humiliations were the order of the day.

When I was in a bad mood, he would spank me on the bottom with a stick.

He doesn’t have good memories of school either. Heinz Kräuchi remembers that the teachers tended to suddenly break out in violence against the students. The teacher checked the students around the clock, even at night in the dormitories.

The director of the home became violent several times: “When he was in a bad mood, he took my head between his legs and spanked my butt with a stick.”

child labor in the fields

The children’s everyday life was strict: getting up at half past six, then school and field work for the farmer on the farm that belonged to the “pit”. The boys had to work for hours: harvesting beets, collecting potatoes, haymaking and chopping wood. There were seldom breaks.

Legend:

The children were forced to work in the fields.

Heinz Kräuchi

Escape from this system was not possible. “Where could we have gone?” asks Heinz Kräuchi. He was allowed to visit his mother once a month over the weekend. He didn’t tell her how things were going for him in the home. He didn’t want to burden her any further.

Resistance was futile

The case of the Kräuchi family is typical of this time, explains the historian Tanja Rietmann. She conducts research at the interdisciplinary center for gender research at the University of Bern, including on compulsory welfare measures and out-of-home placements. She says: “It was often people who belonged to a lower social class who were targeted by welfare.”

These decisions were not questioned. There was supervision, but: “It was not implemented. There weren’t even minimal regulations. And once a decision had been made, there was no escaping it.”

On the contrary: Anyone who tried to defend themselves against a decision by the authorities was considered suspicious, Tanja Rietmann continues.

Mostly unprocessed

The events in the “pit” relate to the 1960s up to the year 2000. The historian assumes that 1,000 boys were affected during this period.

However, the children’s home was founded in 1825. However, almost nothing is known about the fate of the children housed there before the 1960s.

Legend:

Once a year, the homes from the canton of Bern met for a sporting competition.

From Antonio Ragusa’s photo album, ca. 1975

There were several hundred such homes in Switzerland in the 19th and 20th centuries. Tanja Rietmann therefore assumes that thousands of affected children have experienced something similar to Heinz Kräuchi. Very little is known about the fate of these children in care. The “Grube” is one of the few homes whose history is now being worked up.

Affected people suffer for a lifetime

In 2013, Federal Councilor Simonetta Sommaruga apologized on behalf of the state government for the suffering caused by the compulsory welfare measures. Those affected would be entitled to the federal solidarity contribution: that is 25,000 francs. But many suffer for life after their time in the home.

Legend:

Is it all just for show? On the 150th anniversary, the Federal Council is shown that boys are being educated here to become future recruits. Former “Gruebeler” remember that they felt like monkeys on display.

State Archives of the Canton of Bern, 1975, Hugo Frutig

“Many have failed, slipped, committed suicide,” says Rietmann, who also works with her students on the files of those affected. “Only the strongest have succeeded in building a life of their own.”

For the historian, this shows the paradox of these protective coercive measures, which were in force until 1981: “The effect was the opposite of what one had actually hoped for.”

“The basic trust is missing”

Heinz Kräuchi managed to build up an independent life despite the home experience. But he also had crises: he broke off two apprenticeships and struggled with depression.

Legend:

Escaped: Heinz Kräuchi managed to build a life for himself despite the traumatic experiences.

Sabine Gorge

Many of his acquaintances lived on IV or social security, he says. Most would live alone and would have trouble maintaining relationships because: “The basic trust in fellow human beings is missing.”