In 2017, advocates of detachment from Spain still fought at the ballot box. Now the support for the split is dwindling in the population. The consequences of the pandemic and war, but also the strife in the separatist camp itself, make the project a long way off.

On October 1, 2017, thousands of Catalans flocked to the polls to vote on secession from Spain. A referendum that the central government in Madrid declared illegal. Accordingly, there were sometimes wild scenes on the streets of the region.

It’s been five years since beating police officers in Catalonia tried to prevent people from voting. The Catalans were to decide in a controversial referendum on October 1 whether their region should secede from the rest of Spain. The pictures of the voting day went around the world.

The regional president at the time, Carles Puigdemont, then proclaimed the founding of a republic and announced that he wanted to negotiate with the central government about the exact implementation. But it didn’t get that far. Because the Spanish government deposed the Catalan government, Puigdemont fled to exile in Belgium where he still lives in the face of the threat of arrest by the police. Several members of his government at the time were imprisoned; However, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez pardoned nine leading figures last year.

Since then, the independence movement has lost a lot of momentum. One reason for this is that the politicians within the independence camp are now fighting bitter small wars and are now shaking the governing coalition. Although the two larger separatist parties, the left-wing Republicans from the ERC and the conservative Junts per Catalunya (JxCat), continue to govern in the regional parliament in Barcelona, their coalition is now only based on 64 of the 135 MPs and cannot set a strategy agree on how to break away from Madrid.

Should Catalonia follow Canada or Puigdemont?

The Catalan Prime Minister Pere Aragonès from the ERC, who has been in office for a year and a half, is primarily counting on dialogue with the central government in order to one day be able to hold a new referendum, this time approved by the central government. He dubbed this approach the “Canadian way” in a general debate in Barcelona on Tuesday. Canada facilitated two secessionist referendums in Quebec, in 1980 and 1995, both of which the pro-independence French-speaking province lost.

Catalan Prime Minister Pere Aragonès, who has been in office for a year and a half, is committed to dialogue with the central government in Madrid.

JxCat, on the other hand, is too tame. Puigdemont still pulls the strings in the party, now from Brussels, where he works as an MEP and enjoys immunity. He and his party friends are sticking to a unilateral course of secession and never miss an opportunity to criticize the dialogue with Madrid as a “waste of time”.

Last week, the directional dispute triggered a new government crisis in Barcelona. Aragonès fired his deputy Jordi Puigneró from JxCat because he had hidden from him that his party colleagues wanted to table a motion of no confidence in the government in Parliament. This project was finally postponed after several hours of negotiations in the coalition. However, the threat of a coalition break-up remains.

If there were a break, Aragonès would have to call early elections or he would have to seek a new majority, for example with the left-wing party platform En Comú Podem and the Catalan sister party the Socialists (PSC), which, like the PSOE, rejects his independence plans. In Madrid, meanwhile, they are trying to keep the Catalans happy with concessions regarding more self-government and investment plans for infrastructure projects. Because: Pedro Sánchez’s minority government is dependent on the support of the twelve ERC parliamentarians in the Spanish House of Representatives for important votes.

The region is no longer an island of prosperity

The party strife is also depressing the mood of those who followed the independence movement five years ago. This was also recently shown on the Catalan national holiday. In 2017 and 2018, more than a million Catalans roamed the streets to demand their own state, but this year there were only around 150,000 people, according to the city police. Meanwhile, the organizers spoke of 700,000 demonstrators. “If we didn’t have politicians, we would have been independent long ago,” said one of the banners. The regional president of Aragonès did not take part in the march for the first time this year after being whistled at last year by impatient activists.

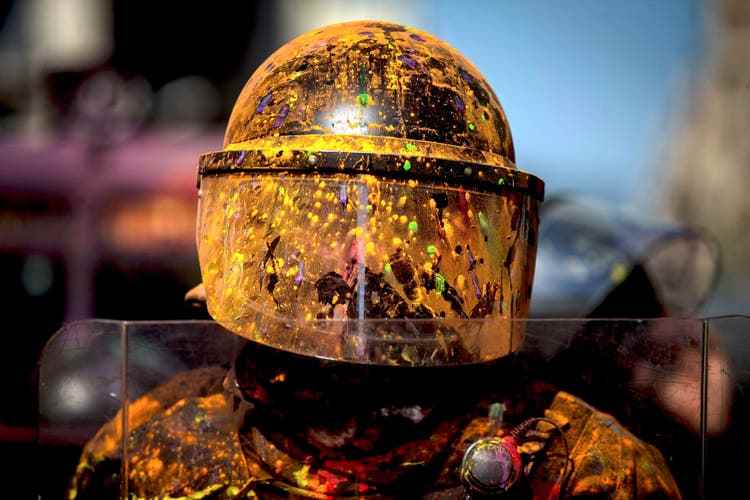

A riot policeman who was sprayed with paint by supporters of the Catalan independence movement. The protesters tried to enter the local headquarters of the National Police in Barcelona on September 29, 2018.

According to a recent survey by the Catalan opinion research institute CEO, only 41 percent of the Catalans surveyed want an independent state. For the past decade, nationalists have always had the upper hand in Catalonia. At the time, they also benefited from the good economic situation and the argument that the wealthy region had to give too much tax money to the central government. In addition, the language, history and culture of Catalonia should be defended.

But in recent years, the economy in Catalonia, like the rest of the country, has been suffering from the consequences of the pandemic. Now the energy crisis and high inflation are getting on our nerves and our wallets. People’s priorities have shifted. Catalonia is no longer an island of prosperity.