Factory halls on the Maag site, several large housing estates and even three high-rise buildings near Triemli are to be demolished. Now the resistance against this Zurich demolition fever is growing.

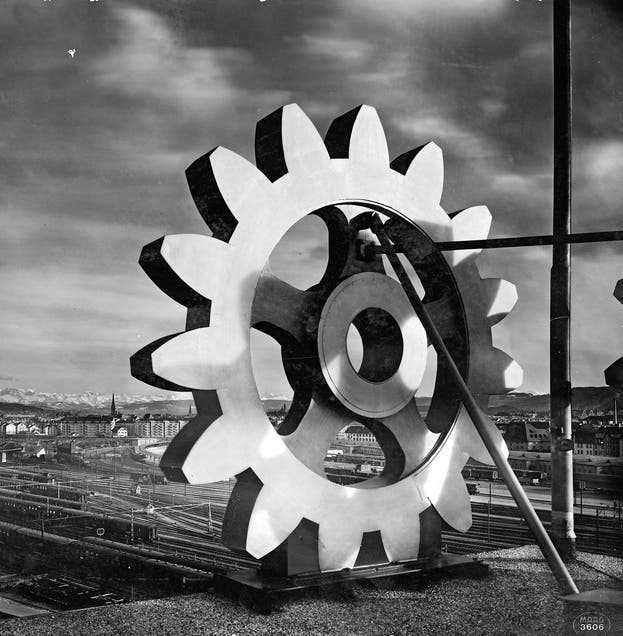

A look back at the time when the Maag gear factory was still producing on a large scale.

At its annual media conference at the beginning of the year, the real estate company Swiss Prime Site (SP) announced rather casually that it wanted to demolish the Maag factory buildings that had been used for cultural purposes in recent years and replace them with a new building by the Berlin architects Sauerbruch Hutton. As SPS itself said, this is intended to set the “keystone” in the conversion of the huge factory area on which gears of all kinds were once produced.

Immediately after the announcement, a wave of protest against the planned demolition arose, which has not stopped to this day: Thousands signed a petition to preserve the factory halls, including many renowned Swiss artists who had been in the halls of Maag Music in recent years & Arts AG. The Federation of Swiss Architects (BSA) protested in a communiqué, and the Swiss Homeland Security put the factory buildings on the red list of threatened buildings.

Now the Zurich homeland security is laying with a broad publication after, in which the history of the buildings, the course of the architecture competition and legal aspects of the planned conversion are examined in detail. The little book appears as a New Year’s sheet of the Heimatschutz, which, however, because of the still rampant epidemic, cannot be purchased on site on Berchtold’s Day, but can only be ordered afterwards (see info box).

At the beginning of June, the public learned that the demolition of the halls was not planned from the start. Although Swiss Prime Site was not obliged to do so, it had organized an architecture competition aimed at examining both: demolition and new construction or further construction with parts of the existing halls. Two offices were shortlisted; Lacaton & Vassal from France, who wanted to keep all the halls, and Sauerbruch Hutton from Berlin, where only a protected house of the former factory ensemble survives.

The factory buildings in the early days of the Maag cogwheels.

Distinguishing feature of the factory.

The building K.

Building K, the hardening shop, must be preserved in any case. The characteristic cog on the roof of the former factory disappeared years ago.

In the end, SPS decided on the complete demolition option. As Axel Simon explains in the homeland security publication, there are various reasons for this: The variant is flexible, both in terms of later use and in the planning and construction process. The big plus point of the project is the open, tree-lined space that is to be set up where the factory halls still stand today.

A very central reason that spoke against the preservation, however, were legal reasons. Some of the halls are located outside the construction areas as stipulated by the special building regulations. You could adjust this, but a revision of the basics would be necessary. “SPS did not want to bear the associated project risks and delays.” Richard Heim, who was previously responsible for land use planning in the Office for Urban Development, addresses this question in his contribution. He writes that only two building boundary lines need to be removed. “This would be possible within a short time,” said Heim.

View of the factory site in the sixties.

The well-known economic historian Hans-Peter Bärtschi goes into the eventful history of the Maag area in his contribution. Among other things, one learns that before the Maag company, one of three car factories located in Zurich-West was producing on the site. It was the Safir brand, which began building cars in 1906, but had to file for bankruptcy a few years later. Max Maag began building cogwheels in 1913. But personally, he was not granted a long career on the area named after him; just ten years later he was pushed out of his own company by banks and large corporations.

The Maag area is just one example of the resistance against planned total demolitions. For example, a group of young architects wrote on the online platform Tsüri against demolition as a supposed matter of course. For example, they have their sights set on the three former staff skyscrapers of the Triemli Hospital, which have been on the drop-off list for years, although they could still be of good service. The group is called ZAS, by the way, and thus ties in with the great tradition of the Zurich working group for urban development that helped shape the discussion about Zurich’s urban development from 1959 onwards. Among other things, she tried to prevent the demolition of the meat hall on the Limmat or the construction of the expressway Ypsilon.

City replaces entire settlements

The city of Zurich with its housing estates has also come into the focus of critics. For some years now, entire settlements have been increasingly demolished and replaced. At the end of November, the electorate approved this procedure for the Hardau 1 settlement, and the competition for the replacement of new buildings at the Salzweg settlement was recently concluded. 130 apartments are to be demolished and over 200 new ones are to be built. The architect of the estate in Altstetten, which opened in 1969, was by the way Manuel Pauli, one of the most renowned planners in Switzerland at the time – and also a member of the ZAS.

Instead of demolishing entire settlements, the existing buildings could be expanded, superstructures condensed. This may be more complicated in individual cases, but it certainly saves on the gray energy that is in the existing buildings. Incidentally, the discussion has already reached the local parliament in this form; In the debate about the 2040 climate target, attention was drawn to the problem of total demolitions on various occasions.

It is no coincidence that the discussion was sparked this year. The statistics show that an above-average number of apartments have been demolished in the current year. In the first three quarters there were 1,496 apartments. That is significantly more than in any of the previous ten years.

New year sheets by mail

ak. The production of New Year’s leaves and their sale on January 2nd, Berchtold’s Day, is one of the oldest customs in the city of Zurich and has its roots in the Middle Ages. Production was also busy this year, but due to the ongoing epidemic, sales are only planned for individual companies. The range of topics extends from the Constaffel’s toboggan (Antiquarian Society) to the Neumünster holiday home near Mollis (learned society) to the book of honor for women (Society of Fraumünster). An overview with the reference locations was published in the daily newspaper of the city of Zurich on December 22nd. The corresponding e-paper is also available online: www.tagblattzuerich.ch.