With the collapse of the Soviet bloc and then Russia’s monetary problems in the 1990s, original ideas flourished. And if it is possible to transform missiles into satellite launchers, why not launch them directly from a submarine?

However, the concept has since been shelved.

Russia has incredible talent

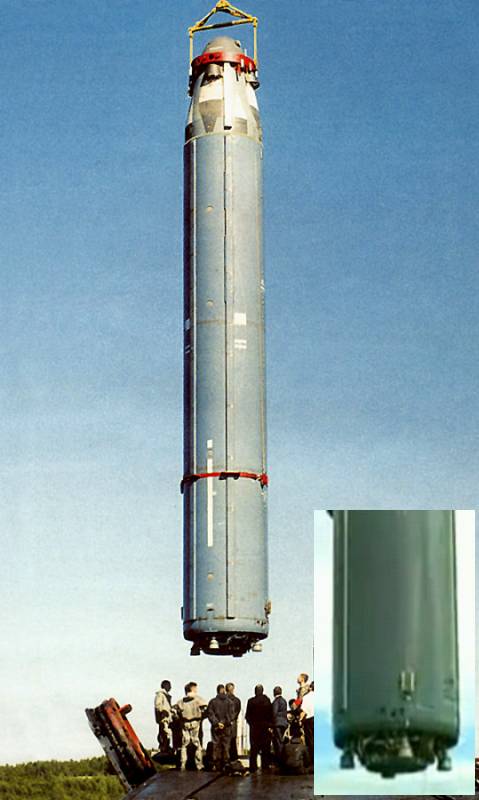

The R-29R missile is not a toy. About 35 tons, capable of sending multiple nuclear warheads at a distance of 6500 km, the one that was nicknamed the SS-N-18 by the NATO powers was precisely designed to annihilate them. A weapon at the heart of the Cold War, taking off from Soviet Delta submarines, which carried 16 each. Rising from the ice floe, the Barents Sea or the North Atlantic, these ballistic missile submarines (SNLE) participated in nuclear deterrence. The Soviet fleet had an imposing number of these submarines at the end of the 80s, and during the collapse of the Soviet Union, it was almost 40 Delta-class submarines (of different generations) and their crews which have been docked.

Of course, part of it continued to sail, and even during the most difficult years for the current Russian budget (around 1996), part of the SSBNs did not stop patrolling. But during this period, everything is good to try to make the investments profitable, while keeping as many talents as possible in Russia. Do ballistic missiles make good orbital launchers?

conversion therapy

On paper, this is indeed an attractive option. Ballistic missiles are reliable materials that can by definition remain stored for a long time with their propellants loaded, and precisely transport payloads which for the R-29R exceed 1.6 tons. From there, why not add a small upper stage to send one (or more) small satellite into low orbit? Of course, foreign powers must be warned that the submarine is planning to launch a satellite and not a thermonuclear warhead, because the military tends to get nervous, but if everything is done properly, it should work. Of course, the first launches are suborbital: in the 90s, there are few private possibilities for these payloads, and the missiles do not even need to be modified to send small payloads for a few tens of minutes in weightlessness.

Touched flowed

Immediately said, immediately proposed. The advantage of a submarine on an orbital base is that it can move and therefore aim for energy-saving trajectories… But then authorizations are needed, and Delta submarines, even for a “demilitarized” shot remain warships. As a result, the first shots will only take place from the Barents Sea, north of the Arctic Circle. It is a barely modified R-29R missile which begins the campaign in 1995, which will take the name of “Volna”. The shooting takes place on June 7, and it is a success. But Volna does not carry an upper stage, and is therefore limited to suborbital flights. This launcher is very little known, for a good reason… His three other flights were failures. During the 2nd launch in 2001, payloads, including a first US Planetary Society solar sail experiment, failed to eject from the missile. The last two shots are equally contrasting, dedicated to a prototype inflatable heat shield that just won’t work.

It’s all in the tube

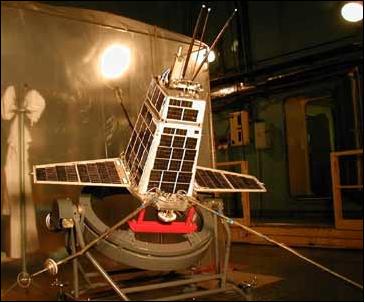

Another R-29 rocket/ex-missile will take off from a submarine on October 4, 1997, 40 years to the day after Sputnik. But this was again a suborbital shot (the version uses an older SS-N-8 missile and therefore only two propellant stages). It will be necessary to wait until 1998 to see the first satellite in orbit which could take off from a submarine! The first two, even, TUBSAT-N and TUBSAT-N1, with a mass of 8.5 kg each and minimalist dimensions (32 x 32 x 10cm). Funded by Germany, these are antenna technology demonstrator satellites and small transponders. They take off from the K-407 Novomoskovsk submarine, still from the Barents Sea, on a modified version of the R-29RM (SS-N-23) missile named Shtil’. The latter is more powerful than its cousins used so far and therefore capable of reaching a low orbit of 400 x 772 km altitude.

Some hail the feat with clenched jaws, because a commercial market centered on the impressive stocks of Russian ballistic missiles could lead the launcher sector into a crisis… And bring large capital to the Russian Navy, which remains despite the “commercial” service recipient of a large part of the funds. Others see the same success looming for the Navy as for their colleagues in the land forces, whose ex-missiles are regularly used as orbital launchers: Dnepr, Rockot, Strela are already in operation.

Shtil’ loving you

However, whether due to competition from these other demilitarized missiles, or to other economic parameters (or even to the reputation of Russian submarines after the Kursk disaster in 2000), orbital take-offs from launcher submarines many machines did not find the success that had fallen to them just before the 2000s. Despite the success of the first take-off from Shtil’ in 1998, there will be no other orbital attempt in 7 years! And here again, the reliability is not really there: a shot from Volna-O, modified to be able to send a hundred kilograms into low orbit, fails in turn with a new attempt by the Planetary Society to send a solar sail. In May 2006, however, Shtil’ succeeded in its second take-off with an 80 kg satellite, Kompas-2.

Here again, we believe the market has revived. South Africa signs for an additional flight, other versions of Shtil’ with a modified fairing and even with launches from modified silos on land are planned. It just… They’ll never happen. These “microlaunchers” before their time do not take, the restrictions linked to the military nature of the shots, but also the logistical difficulties complicate the task for launchers which are already not very powerful. Light satellite operators end up turning to other solutions (departures from the ISS, take-offs grouped with other microsatellites, and nowadays microlaunchers like Electron from Rocket Lab).

History will remember that this original idea did not take hold… yet. Before his return, like ship-launched rockets?

5