Italy’s parties are abandoning the consensus that was a condition of Mario Draghi’s reform policies. His departure is only logical, but plunges the country into a lasting crisis at the wrong time.

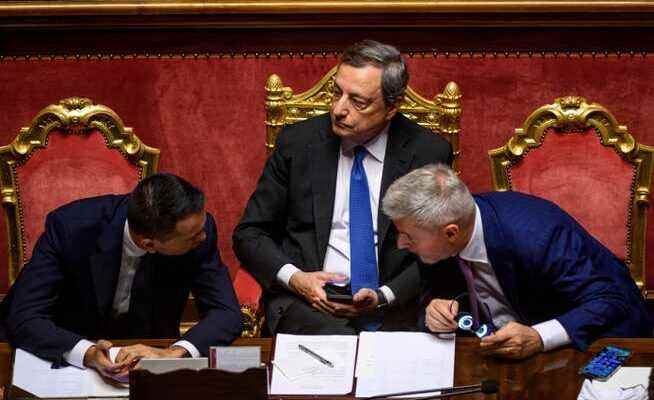

Foreign Minister Luigi Di Maio, Prime Minister Mario Draghi and Defense Minister Lorenzo Guerini take part in the debate following the communications to the Italian Senate.

Italy has formally kneeled down its prime minister. The President flatly rejected his resignation last week and asked him to remain in office. In the past few days, civil society in the country has supported this wish with unprecedented vehemence: Important party exponents, business representatives, university rectors, almost 2,000 mayors from all political camps and, last but not least, demonstrators in the big cities have been urging Mario Draghi to continue to lead the fortunes of the country.

The newspaper “La Repubblica” summed up the mood in a caricature: “Only God knows how Draghi will decide,” says one character. “And he’ll sign an appeal right away,” replies the other.

— Ezio Mauro (@eziomauro) July 19, 2022

This almost imploringly expressed appreciation touched Draghi, as he said himself. For all his sobriety, the former head of the central bank is not entirely unpretentious and is well aware of his immense importance for Italy’s stability. It is therefore all the more understandable that the head of government no longer wanted to put up with the undignified bickering of the parties in recent weeks and presented them with a clear choice: he could only continue his work with the support of the broad alliance of national unity that had set him up one and a half years as crisis manager.

The populists have only one choice in mind

Neither public pressure nor Draghi’s reminders of the parties’ sense of responsibility were of any use. Above all, the populists of the Cinque Stelle and the Lega have only had the elections in their sights in the last few days, not the fate of Italy. However, “Super Mario” cannot continue without the backing of the strongest political forces, despite the renewed confidence in him in Parliament.

He was brought in in early 2021 with a mandate to tackle the daunting challenges Italy was facing at the time: the pandemic, the economic hardships it brought and the structural reforms that Brussels is demanding for the money from the Covid recovery fund to be paid out. With the Ukraine war, an impending energy emergency and the devastating drought in large parts of the country, further trouble spots have emerged. They require a show of strength from everyone, something Draghi has always stressed. That consensus was broken on Wednesday. His departure is therefore only logical.

Draghi leaves the political stage with his head held high, leaving only losers behind. First and foremost Italy, which is now being paralyzed by an election campaign at the wrong time. Sure, the government would have had only six months anyway. But you will feel their absence. But there are also concerns in Brussels, Washington and Kyiv. Draghi was not only a guarantor for reforms and economic reliability, but also for the unconditional support of the transatlantic alliance in the Ukraine war. In the Kremlin, his untimely demise will be greeted with joy.

The Cinque Stelle have been overwhelmed for years

Italy’s political class also paints a pitiful picture. The Cinque Stelle, beaming winners of the last election, have been overwhelmed at the controls of power for years. In the last few days, they dismantled themselves in public. Her boss Giuseppe Conte, who was once celebrated as head of government for his handling of the pandemic, pushed for the overthrow of his successor Draghi. According to polls, however, he will pay for his success with his party falling into insignificance.

The Lega is not in much better shape, whose chairman Matteo Salvini could never really decide whether he wanted to be part of the unity government or run the opposition. The right-wing camp is likely to win the election, but Salvini is likely to have to hand over its leadership to the post-fascist Fratelli d’Italia. What a stable coalition should look like under these circumstances is a complete mystery.

In the past year and a half, Draghi has shown that a different policy would also be possible in Italy. He was never elected, yet he enjoyed widespread support – not for his charisma or flamboyant promises, but for his seriousness and drive. A little earlier than expected, party politicians are now taking the helm again. The pleading appeals to Draghi show how little the Italians think of it.