For decades, Hans Modrow served as a functionary of the GDR. He also messes with Erich Honecker from time to time. During the period of reunification Modrow is one of the few SED hopefuls, but he cannot save the GDR either. In the last years of his life he works his way through his party.

In the past few years, Hans Modrow has been quiet. Old age took its toll. But the quarrels within his party Die Linke have also weighed heavily on him. At the beginning of 2022, at the age of 93, Modrow spoke up again. After the Left Party’s severe defeat in the 2021 federal election, he wrote a letter to the then top left-wing duo Janine Wissler and Susanne Hennig-Wellsow. A letter was a kind of reckoning with the party and its current leadership. Modrow had in mind the ultimate failure of the first serious party to the left of the SPD for decades in the Federal Republic of Germany. Accordingly, he went to court with the left leadership.

The left is no longer clear about “what its purpose is,” said Modrow. He wonders why voters should vote for a party “whose primary interest is to form a government with the SPD and the Greens.” It was the communist who reappeared in the longtime SED top functionary: uncompromising on issues, turned to the past on the coalition question. Better permanent opposition than swallowing political toads.

In March 2022, Modrow, in his capacity as chairman of the Left Council of Elders, caused a stir with statements about the Russian attack. In a letter to the party executive, he “raised the question” as to whether the war was an invasion of Russian troops or an “internal civil war between the forces in the new eastern states and fascist elements in western Ukraine.” . Modrow withdrew from the committee a little later.

Holidays in Crimea during the coup against Gorbachev

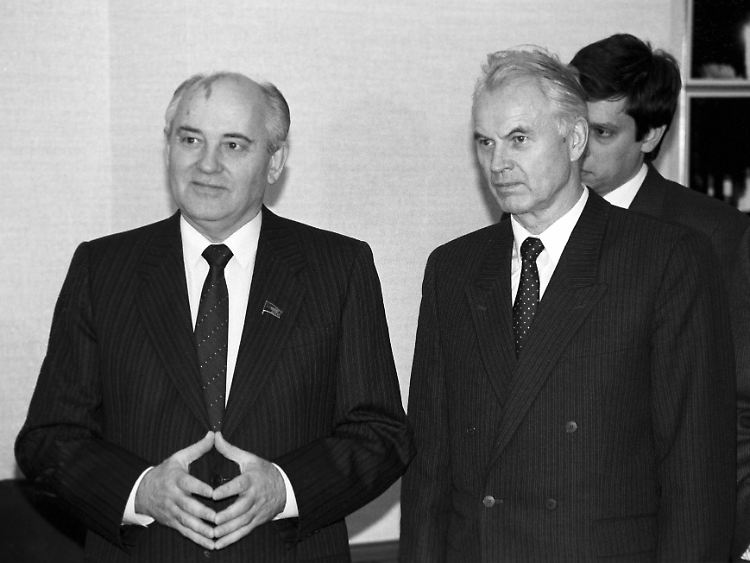

There were sometimes strange episodes in Modrow’s biography: During the coup of conservative forces of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in August 1991, he was on vacation with President Mikhail Gorbachev on the Crimean peninsula. In the early morning of August 19, while Gorbachev was residing in his dacha “Dawn,” Modrow was jogging in front of his estate on the Black Sea beach.

“I saw Interior Minister Boris Pugo at breakfast that morning. When he left around 10 a.m., I thought his vacation was over – but in the evening I found out that he was a participant in the coup,” Modrow said in a 2011 interview with of the “Junge Welt”: “I only found out much later that the President was under house arrest and his phone had been switched off.” What was still to come for Gorbachev after the failed coup attempt, namely his complete disempowerment and the collapse of the USSR, was already behind Modrow – the GDR had already died almost a year earlier and the SED had lost its position of omnipotence.

Modrow’s relationship with Gorbachev was already broken by this time. He didn’t just resent the Russians for having dropped the GDR. He later also condemned statements by Gorbachev in which he opposed communism and saw the destruction of the Soviet Union as the goal of his policies. “It annoys me that I believed in Gorbachev and trusted him for too long.”

Fight to get the SED

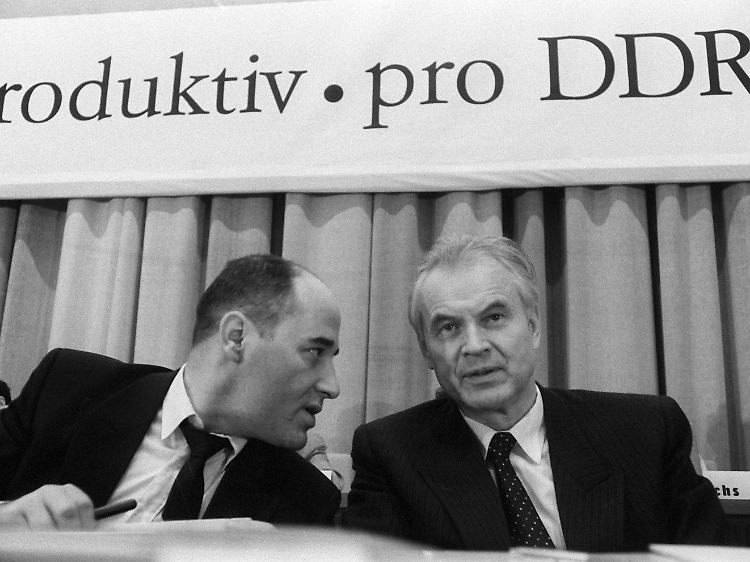

Modrow and Gregor Gysi at the 1st PDS party conference in February 1990 in East Berlin.

(Photo: picture alliance / dpa)

It was the former CPSU general secretary’s political tirade that irritated Modrow during his tenure as East German prime minister. Despite the historic defeat of state socialism in the Eastern bloc, Modrow, who was born on January 27, 1928 in Jasenitz, West Pomerania, never considered an abrupt departure from his decades-old political ideals – for decades he was too closely attached to the defunct system.

So closely that he did all he could to ensure that the run-down SED would not die. At the crisis party conference in December 1989, at which the dissolution of the formerly all-powerful party was up for debate, it was Modrow who made the decision in favor of the continued existence in a closed night session in East Berlin’s Dynamo sports hall. “I have to say here with all responsibility: If, given the intensity of the attack on our country, this country is no longer able to govern because I, the Prime Minister of the German Democratic Republic, have no party to my side, then we all bear the responsibility if this country is going under,” he said.

Well, history then gave its verdict on the GDR, almost 41 years after its founding, it disappeared from the map. Modrow retired from the office of head of government. The first and only free elections in the GDR on March 18, 1990 sent him and the SED, which shed its skin twice during this time and voted as the PDS, into the opposition.

First reformers, then yesterday’s politicians

After the fall of the Wall, there was no longer a chance for the GDR to continue to exist. Apart from the fact that Gorbachev was in dire need of foreign currency due to major economic problems in his huge empire, the East Germans no longer participated either. Within a few months, the reformer Modrow, who was praised in the West immediately before the reunification, mutated into yesterday’s politician. Those responsible in Bonn also let him feel it.

At the press conference during his visit to Bonn on February 13, 1990, he did not hide his annoyance with the federal government. Modrow rebuffed Chancellor Helmut Kohl with his request for an instant loan of 10 to 15 billion Deutschmarks. The prime minister had attempted a liberating act by including eight “ministers without portfolios” from the GDR opposition in his “Government of National Responsibility” a few days before his visit to the Federal Republic.

In vain, because Kohl’s national goals were already broader: currency union and German unity. The power man from the Palatinate didn’t want to help Modrow in the election campaign in order to prolong the GDR’s dying process. Bitterly, Modrow left Bonn again. He was no longer an important discussion partner for Kohl; the chancellor came to terms with Gorbachev, who no longer stood in the way of German reunification.

Modest SED functionary

From Bonn’s point of view, Kohl’s actions were understandable, since the election campaign in the GDR was in full swing. The “Alliance for Germany” made up of the CDU, DSU and Democratic Awakening prepared to heave the standard train onto the track. There was no longer any room for Modrow, who had led the GDR through difficult waters and who was credited with preserving internal peace in East Germany. However, he did not completely disappear into political oblivion, as he was still active as a member of the German Bundestag and the European Parliament.

No break with the past: Modrow at the funeral of former East German Defense Minister Heinz Kessler on June 7, 2017 in Berlin.

(Photo: picture alliance / Britta Peders)

Although Modrow made a typical GDR political career, he differed from the leading comrades. In contrast to other top SED officials, he was considered modest and of integrity. During his time as Dresden SED district chief (1973-1989), Modrow lived with his family in a three-room apartment. Under Honecker he was denied entry into the highest circle of power in the SED, the Politburo.

The stubborn Pomeranian crosshead – that’s how he called himself – was not comfortable with the guard of the old gentlemen who had holed up far away from the people in the forest settlement in Wandlitz. Unlike Honecker, Modrow saw a need for reform in the GDR. So it is not surprising that those responsible in Moscow saw him as Honecker’s successor in 1987. However, Gorbachev did not take action and the plan remained the same.

Court verdicts for inciting voter fraud

Reformers or not: During the SED rule, Modrow kept a low profile when it came to assessing glasnost and perestroika in the USSR. His actions as Dresden’s SED district leader at the beginning of the period of reunification were also ambivalent. On the one hand, in the city on the Elbe, he focused early on the dialogue with the opposition “Group of 20”. On the other hand, the security forces under his leadership cracked down on demonstrators. In connection with the passage of a train with GDR refugees from Prague in the direction of the Federal Republic, there were riots in Dresden with hundreds of arrests.

With statements about the Wall dead, Modrow even reaped opposition in his own party. Those responsible on both sides are responsible for the victims, he told Cicero magazine in 2006. For him, the GDR was a state in which there was also “democracy with restrictions”. In the 1990s, several court judgments were issued against Modrow for inciting electoral fraud. But only a suspended sentence of nine months became final.

Hans Modrow never described himself as an opponent of the GDR system. “I wasn’t a hero,” he said. Accordingly, he saw the collapse of actually existing socialism as a personal defeat. Hans Modrow died on Saturday night at the age of 95.