contents

Caroline Buchs is one of the few milliners who can make a living from her job. Thanks to the theater where the rare craft is still needed.

Caroline Buchs discovered her love of hat making by accident. “I took part in a hat workshop during my training as a theater tailor,” says the 52-year-old from Bern.

“I came up with a complicated model, a kind of asymmetrical toque – a brimless women’s hat – made of orange felt with a green croissant on it.” A lofty goal, which she implemented after a week.

The Keeper of Hats

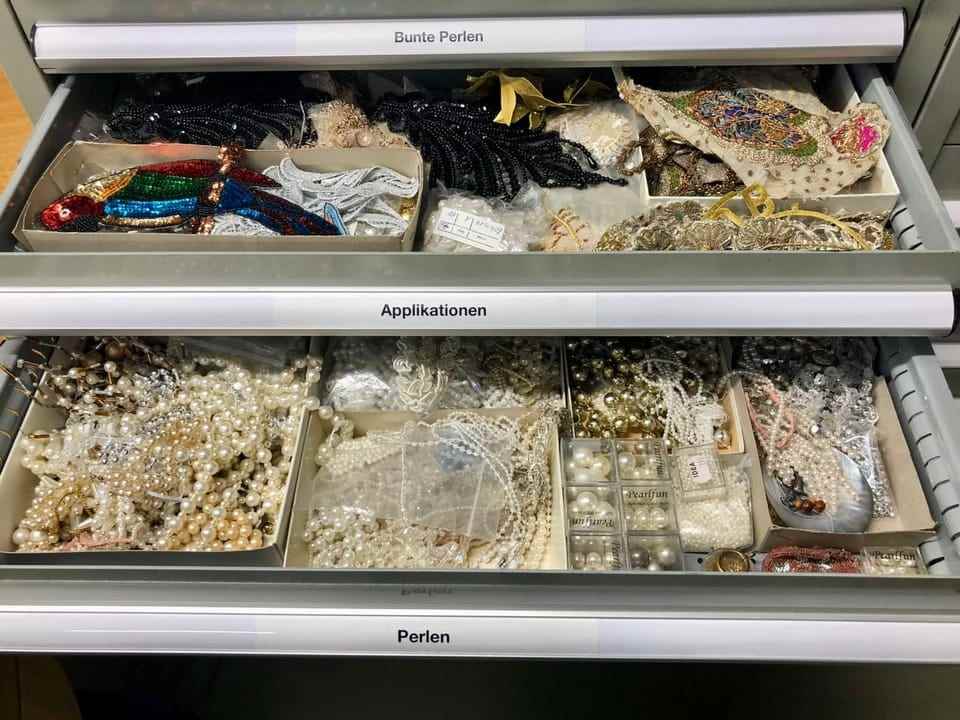

After that it was clear to her: she wanted to take up this handicraft as a profession. Today she works in the hat studio of the Bern Theater. Its premises are located next to the theater tailoring shop. They are full of cupboards filled with beads, sequins, straw flowers and felts. There are wooden molds on the shelves and work in progress for the various productions on the tables.

Studio visit to Caroline Buchs

There is also an industrial sewing machine here, with which the hat maker can sew heavy layers of fabric together as light as a feather. The core is a steam device, a machine that produces hot steam.

Buchs fills the large container with water and turns on the machine. Within a very short time, this emits steam as if a small dragon were snorting. “I moisten the felt with it. If it’s evenly moistened, it’s easier to pull into shape.”

Legend:

With the help of this steam engine, the hatter moistens the felt.

Noëmi Gradwohl

The hat maker works 60 percent at the Bern Theater, her colleague 30 percent. The two are lucky, because positions are few and far between. Because of the changed fashion, hats and caps are hardly in demand anymore. In addition, the materials required are scarce. They often demand craftsmanship in production that is hardly practiced anymore.

High fashion as an alternative

In addition, there is huge competition from Asian low-cost manufacturing countries: “People are used to cheap things these days and prefer to buy a baseball cap for 15 francs. However, the actual effort is many times more expensive.»

If Caroline Buchs weren’t working in the theater, the high fashion sector would be an obvious field of work. She could become self-employed as a hat maker. However, there are only few customers for high-priced hats.

Hats are now worn on exclusive occasions, such as horse racing at Ascot in England. Fashion designers also work with milliners.

Legend:

Daring to wear a hat: Catherine, the Princess of Wales, and her husband Prince William, the British Crown Prince, will be showing their elaborate hats at the Ascot horse race in summer 2022.

Getty Images/Chris Jackson

The Brit Philipp Treacy is probably the best known: he made hats for the legendary collections of the British fashion designer Alexander McQueen. He still supplies the British Royals.

culture on the head

When Caroline Buchs learned the profession of milliner at the renowned Fashion Institute of Technology in New York in the mid-1990s, she was hardly aware of the difficulties. “People wore a lot of hats in New York back then. For example in Harlem at gospel concerts,” she says. “In the winters it was also freezing cold and many wore hats or extravagant headgear.”

After completing her training, her mother drew her attention to a position at what was then the Stadttheater Bern. Since then, the milliner has been felting daring headdresses, sewing entire underwater worlds onto caps or inventing collar caps for plays, opera and ballet.

Her work as a hatter makes it clear: the theater not only serves to preserve culture on stage, but also in its workshops.

Radio SRF 2 Kultur, context, December 9th, 2022, 09:03.