contents

In the distant past, the Central Plateau was flooded by the sea. Researchers have now discovered previously unknown dolphin families.

Meadows, forests and idyllic detached houses as far as the eye can see: for those who live in the Mittelland today, the sea is a distant place of longing. However, around 20 million years ago, Switzerland was part of an island landscape and the central plateau was completely flooded.

The climate was warmer then than it is today. The result: the sea level rose, the seas flooded the low-lying areas of Europe. The arm of the sea in today’s Switzerland was settled by a good 70 species of sharks and rays, but also by numerous species of bony fish and dolphins. Mussels, sea urchins and crabs lived on the seabed.

Researchers at the Paleontological Institute of the University of Zurich have now been able to use fossils to identify two families of dolphins whose occurrence in Switzerland was previously unknown. They are related to the dolphins and sperm whales that still live today.

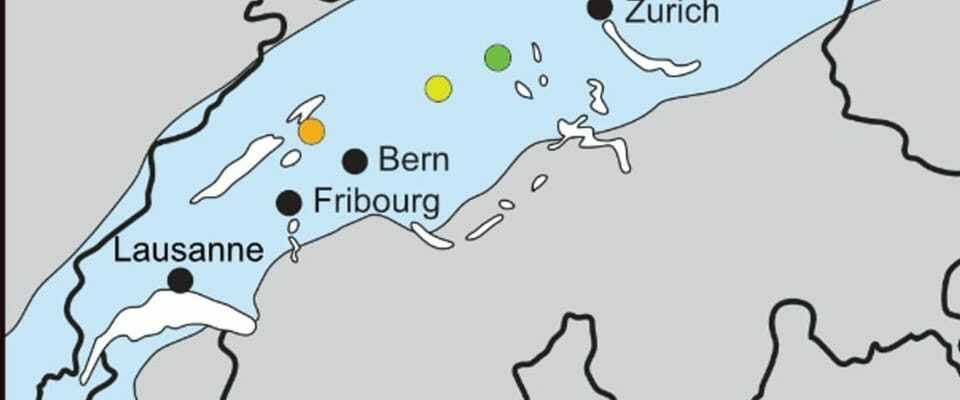

Legend:

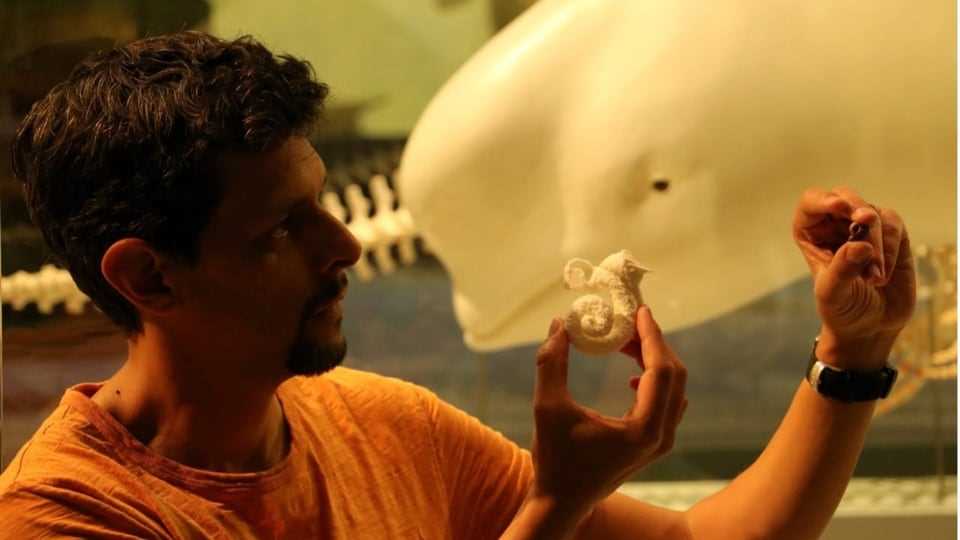

UZH paleontologist Gabriel Aguirre holds up a fossil of a dolphin ear bone (right) and an enlarged 3D print of the inner ear (middle). The spiral corresponds to the cochlea, an organ involved in hearing.

Aldo Benites/ZVG

One of the researchers is Gabriel Aguirre. In contrast to prehistoric sea creatures such as the megalodon basking shark, the dolphins from back then would hardly stand out today: “The dolphins from back then actually looked exactly like the dolphins we know today,” says Aguirre. “The Kentriodon family resembled our oceanic dolphins.”

No fully preserved skeletons

Related to today’s sperm whales, the dolphin family was smaller than today’s sea giants, which can grow to be almost 18 meters tall. The second family of squalodelphinids is related to today’s river dolphins in India, the researcher explains.

Legend:

A depiction of the dolphins described in the study: Kentriodon in the foreground, in the background a squalodelphinid (left) and a physeterid chasing a group of eurhinodelphinids.

Jaime Chirinos/ZVG

The researchers did not find any completely preserved fossils. The then strong currents in the Mediterranean estuary pulled the animal skeletons across the seabed and scattered the bones. “That’s why no complete skeletons can be found today,” explains the paleontologist.

What remained were the hardest parts of the dolphin skeleton, almost exclusively teeth, vertebrae and ear bones. “These ear bones of dolphins are of great interest to science, however, because they differ greatly from one another. You can therefore clearly assign them to a species group.”

Understand the evolution of marine mammals

Thanks to micro-computed tomography, the researchers were able to reconstruct the softer organs around the hard ear bones and create 3D models. “This helped us analyze, discriminate and interpret the dolphins’ hearing abilities, allowing us to draw inferences about their ecosystems.”

In the most important collections in Switzerland there are around 300 fossils of whales and dolphins, which were brought together by scientists and amateur paleontologists. “We owe them the information we can rely on,” says Aguirre.

By discovering the two families of dolphins, he hopes to gain a better understanding of how marine mammals in Europe and around the world have evolved to the present day.