Stadtwerke Osnabrück are promoting their app Yaniq with the offer “bus travel at the best price”. Users can check in with one swipe and then enjoy a contactless all-round carefree ticket. An IT expert with the pseudonym “Kantorkel” warned at the virtual hacker meeting remote Chaos Communication Congress (rC3) that the gain in convenience goes hand in hand with the extensive loss of privacy. “Data retention for local public transport” takes place in the background.

Several transport associations are currently testing so-called check-in / be-out systems (CiBo) to allow users to navigate through the existing tariff jungle more easily. Relevant apps such as Yaniq enable automatic payment via smartphone. Due to a weak point, Kantorkel was able to log into the backend system of the Osnabrück application and to look around undisturbed after the creation of a test user. It was a production environment before official operation. Nevertheless, deep insights into the main features of the procedure were possible.

Mountains of data

What the hackers found surprising was “how much data this system wants”. For example, the location of the users will be tracked via distributed Bluetooth beacons in the buses, via which users are automatically checked out when they leave the vehicles. At the same time, however, GPS coordinates are also collected and “tracked for ten to 15 minutes after getting out”. This second category of geospatial data will be “telephoned home later”.

The app knows, for example, “where you live” when your home can be reached in around fifteen minutes, explained Kantorkel. This becomes clear when someone moves relatively quickly into a building in which there would otherwise not be too many other people. Even movements within the alleged apartment would still be registered. With different levels of reliability, assessed with a special “confidence”, it can be seen in the backend area, for example, whether a user is likely to go for a walk or ride a bicycle.

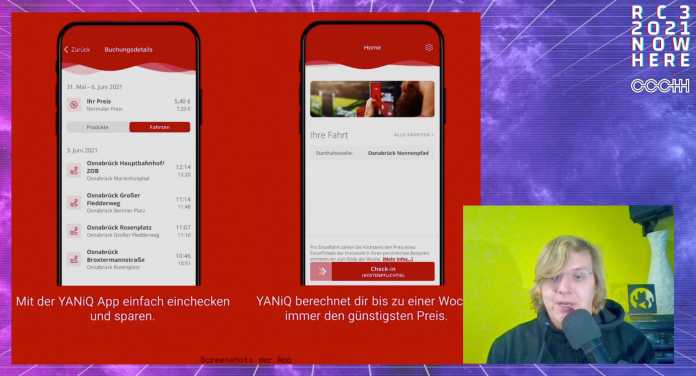

The Yaniq app in the presentation by Kantorkel

(Image: rC3 media.ccc.de, license CC by 4.0)

The activist could not say whether and for how long this sensitive and meaningful information will be stored in the current version. In a question-and-answer list of the Yaniq municipal utilities, it says: “Your personal data will be stored for as long as is necessary for the fulfillment of these purposes” and there are no other statutory retention requirements or statutory justifications. As a rule, personal information would be retained for up to ten years after the end of the contract. When the contractual relationship is terminated, usage data is deleted after two years at the latest.

Visualizations

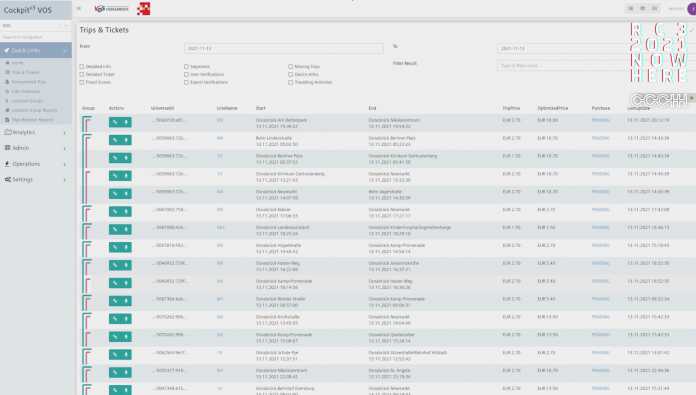

According to the hacker, the public utilities were able to see a pseudonymized “Universal ID”, the time of activities, the final stop and intermediate stops as well as the fare due via an overview of “Trips & Tickets”, according to the hacker. A fraud score is also displayed. In general, information about the cell phones used, the connection quality and various check-in / out events would be collected, which could also be exported anonymously. A backend user can also have data on the beacons output up to their remaining battery capacity.

Using a view on “suspicious movements”, a row is created in a table for each user, in which the app usage is displayed for every hour of the day, explained Kantorkel. For example, it can be seen that a person checked in again early in the morning after a relatively short night and where they had moved to. This is visualized on a map. But Kantorkel also pointed out that fewer messages could be collected in the productive system.

“Suspicious Movements”

(Image: rC3 media.ccc.de, license CC by 4.0)

According to the municipal utilities, in addition to identification data, contract-specific information is processed, with “trip data” being pseudonymised. In addition, there would be “validity features” such as boarding stop, data of the journey, “date and time of the be-out”, lines and transfers as well as “IT usage and log data. You also collect” other personal data such as the IP address, opt-ins and the creditworthiness at the time of the query with the credit reporting agency Creditreform.

Simpler solutions

Kantorkel pointed out that tickets would have to be paid for at some point and that pseudonymization could therefore not be maintained at all times. A “direct connection” to the person concerned is necessary for billing. The provider also uses GPS to make abuse more difficult. It is possible to switch off the app “when you have got out”. What influence this has on the billing process is unclear.

The expert appealed to Yaniq users to query their data history from the municipal utilities in order to shed light on the actual storage. It would certainly be possible to create the whole thing more sparingly. In general, for simpler tariffs, he said, he said, a day ticket for two euros or a pay-as-you-go public transport, as the “Just get in” group is calling for, using the example of Bremen. It was also not the first loophole that he investigated in mobile ticketing apps. At least in the case of Osnabrück, the reporting process at the municipal utilities, Siemens and the Hamburg ticketing solution provider eos.uptrade was “pleasantly calm”. He also informed the responsible data protection authority.

(jk)