Living in isolated communities in Brazil, the Quilombolas fight for recognition and inheritance from their ancestors.

A census is currently taking place in Brazil. For the first time, members of so-called Quilombo communities, which were founded by escaped slaves, are also counted. Their descendants hope that, thanks to inclusion in the census, they will finally be recognized as full citizens of Brazil.

View of Ilha Mare.

Ilha Mare is located in northeastern Brazil, not far from Salvador. Several quilombos are there, Marizelha Carlos Lopes lives in one of them. Since dawn, the 52-year-old has been collecting seafood, opening clams and cracking crabs to put food on the table for her family. She says: “Participating in the census is one way to fight back. One of our goals is to escape intentional invisibility.”

The sea determines the life of Marizelha Carlos Lopes on Ilha Grande.

Marizelha Carlos Lopes prepares crab meat.

There is no bridge to the mainland on Ilha Mare, and cars are prohibited. The inhabitants move from place to place like their ancestors: on foot, on horses or in boats. They also live like their ancestors. Fishing, weaving baskets, in the evening we dance or talk together. Fishermen say their livelihoods are threatened by pollution. In 2013, a boat loaded with propane exploded at a nearby port. Marizelha Lopes recalls that an entire fishing and tourism season was lost to pollution as a result. “There are still no specific studies or public measures that guarantee our safety,” says her nephew Uine Lopes, who proudly wears a picture of his grandfather on his forearm. “We have no escape route.”

Uine Lopes presents his tattooed arm showing his grandfather fishing.

A woman weaves baskets at Quilombo Praia Grande on Ilha Mare.

The Quilombos – the word comes from the Bantu languages and means settlement – were founded at the time of Portuguese colonization by escaped slaves. The isolated residential communities emerged in remote forests, on mountain ranges or islands like Ilha Mare. They were not marked on official maps for a long time. Even today, 134 years after Brazil became the last country in the western hemisphere to abolish slavery, many of the residents are still treated as second-class citizens.

A teller interviews residents in Quilombo Praia Grande on Ilha Mare for the Brazilian census.

Two men ride their horses in the sea in front of the Quilombo Banairas on Ilha de Mare.

The National Quilombo Association Conaq has identified nearly 6000 Quilombo areas nationwide. Under the presidency of Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva between 2003 and 2011, they received more formal land rights and support for cultural programs, says Antonio Juao Mendes, Conaq chairman. Incumbent President Jair Bolsonaro, on the other hand, has dismantled many of these programs and delayed the recognition of further quilombos.

Bolsonaro was even fined 50,000 reais ($10,000) in 2017 for insulting Quilombo residents by saying that “they do nothing” and “are not even fit to reproduce”. An appeals court overturned the case because Bolsonaro was a federal lawmaker at the time.

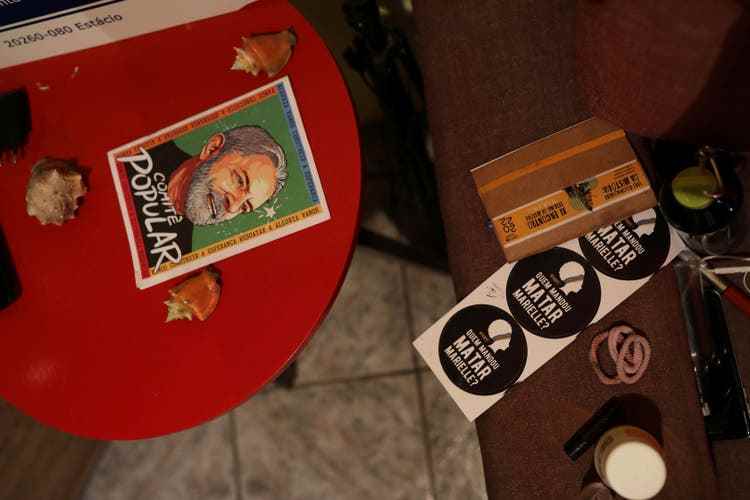

One sticker shows former Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva. The Quilombolas hope that Lula da Silva will now replace Bolsonaro.

Young Uine Lopes is out at sea at 3 a.m. to catch fish. Then he goes to the mainland to study at the university. He says the younger generation of islanders is increasingly aware of the common cause they share with other minorities and marginalized communities in Brazil. “We need to be aware of this and elect as many black people as possible who are committed to the struggle, who have concrete visions for the indigenous communities, the quilombolas, the fishermen, the riverside dwellers and so many other communities that need it government support is lacking.”

Uine Lopes (right) is out with a colleague to catch fish.

One who wants to be chosen is a friend of Uline’s grandmother. Eliete Paraguassu is the first woman from Ilha Mare to run for a seat in the Bahia State Parliament. She wants to fight against the environmental racism that her community faces, she says. In the run-up to the October 2 election, she traveled to nearby cities to rally supporters. Their slogans: “My voice will be anti-racist”; and «Justice for Marielle».

Eliete Paraguassu fights for votes.

The latter is a reference to Marielle Franco, a black councilwoman in Rio de Janeiro who fought for racial justice and was shot dead in 2018. Her legacy is an encouragement to black women like Paraguassu. Of the 513 lawmakers elected to the lower house of Congress in 2018, just under a quarter identified themselves as black – and only 12 of those were women. This compares to 50.7 percent of people who identified themselves as black in the 2010 census.

Eliete Paraguassu wants to go to the Bahia Parliament.

Marizelha has no political ambitions and is less educated than her nephew Uine Lopes. She only went to school up to fifth grade. But her nephew’s combination of academic pursuits and community service inspired her. “I’m increasingly convinced that universities are important,” she says. To add: “But our resistance and struggle is what arms and prepares us for confrontation.”

Marizelha Carlos Lopes laughs while talking to a friend (not pictured).

A fisherman off Ilha Mare is hoping for a big catch.

Images: Amanda Perobelli/Reuters