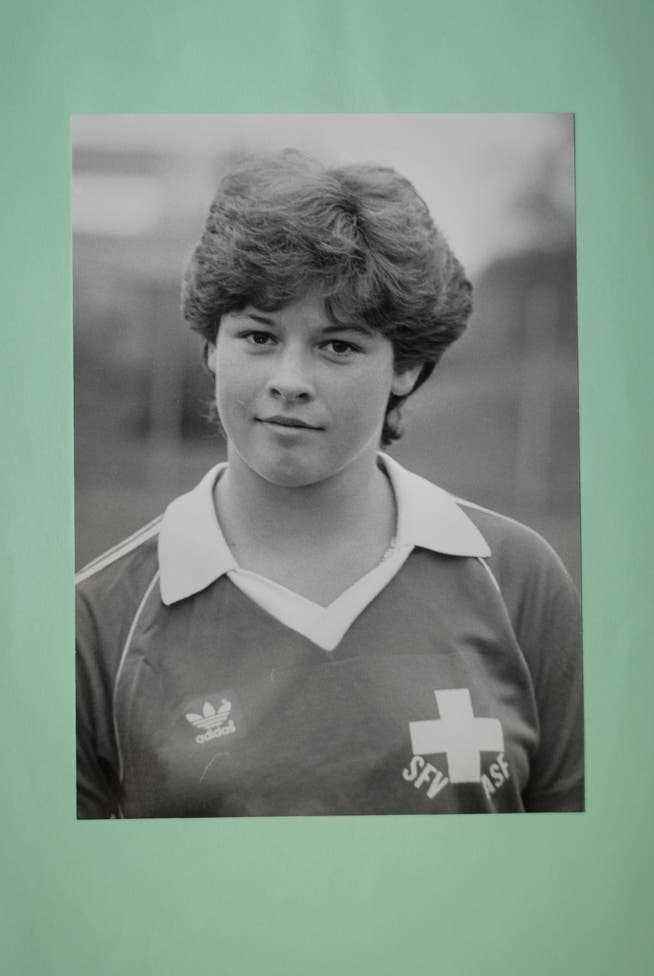

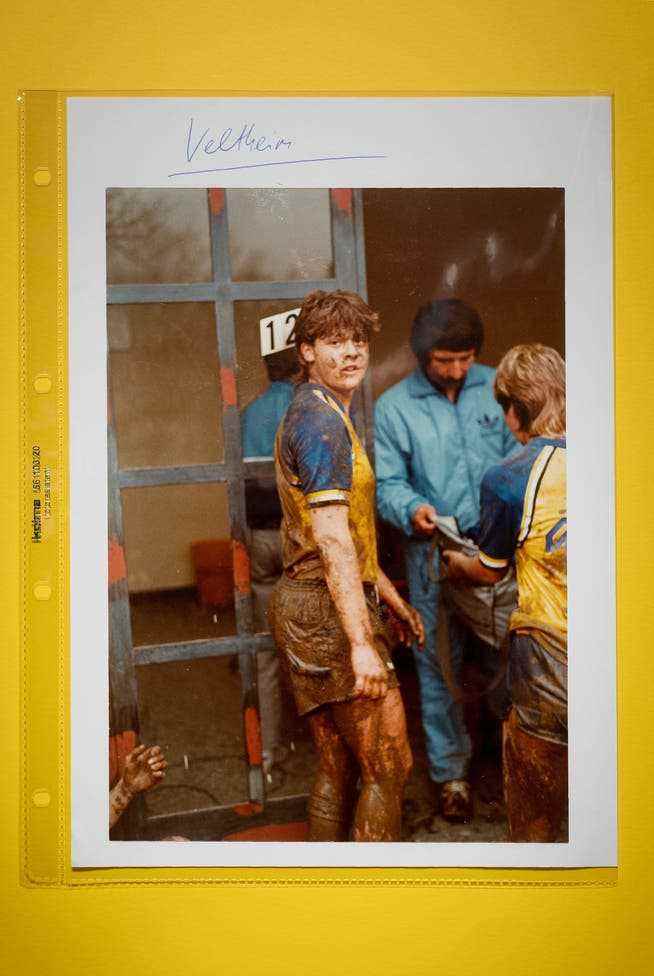

A child among women: Sonja Stettler, née Spinner, below left around 1980 at the age of 11 in the SC Veltheim team. Reproduction: Christoph Ruckstuhl / NZZ

She was in the national team at 14 and made international matches that didn’t count: how Sonja Stettler paved her way through football when attention didn’t mean respect.

Her old life is wrapped in a yellow folder. Her old life in which she scored 13 goals for the Swiss national soccer team. In officially 51 international matches. Although there are more.

It is the life of Sonja Stettler, née Spinner, born in 1969. When she was asked to say what her dream job was as a girl, she said: “Football professional.” It was a dream, a dream doesn’t have to be realizable, “it wasn’t back then,” says Sonja Stettler today. “Others said: I want to go to the moon – which was probably just as utopian back then.”

The yellow folder is bulging. The family seems to have collected everything about Sonja Stettler’s football career, from the first word to the last, from the first step to the last.

Only six players have scored more goals for Switzerland, Ana Maria Crnogorcevic, Lara Dickenmann, Ramona Bachmann, Fabienne Humm, Martina Moser and Rahel Kiwic. Players who are taking part in the European Championships these days or – like Dickenmann and Moser – have shaped this generation.

But Sonja Stettler comes from a different generation, from a time when she made these official 51 international matches; in which participation in the finals was as utopian for Swiss women as a flight to the moon. Sonja Stettler played in the national team from 1984 to 1998, but a number of appearances have disappeared somewhere because only those games are included in the statistics in which a player was on the field for at least half time.

“At some point this changed,” says Sonja Stettler, “it was adapted to the men. But before that: you played there and you were still in zero international matches.” She says it with a certain amusement. Because her old life took place in a different time. When it was how it was.

Before the first international match: Sonja Stettler, at the age of 14 in the national team for the first time.

As a child, she had teammates who were in the middle of life

Stettler was 14 years old when she played for the Swiss national team for the first time in spring 1984, the youngest debutante at the time. And she was 11 years old when she first played in the top division. She had taken part in a grumbling tournament, and a man approached her father and said: “He’s a talent, where does he play?” The father replied: “He doesn’t play anywhere because it’s a girl.”

Football was in the blood and in the family, her brother, eight years her senior, took Sonja to football when he should have been looking after her. That’s what it says in some texts from the past, and that’s how she still tells it today. The history of life does not change, only the perception.

Immortalized in the yellow folder: Sonja Stettler after a match with the SC Veltheim women at an Easter tournament in Ticino.

In the summer of 1980 she joined SC Veltheim, she played in the first team with women. Sonja, the child, the others in the midst of life. It was easy, every step, she took it and had fun with it. Only before being called up for the first time in a B national team were there conscious discussions about pros and cons with parents and coaches. “But they realized: we can’t take that away from her. One wondered: does it make sense now? Or would she be overwhelmed, not athletic, but human? But when you’re passionate about something, can you get overwhelmed? I don’t know it.”

That’s often the case in this long conversation with Sonja Stettler at the end of June. Sometimes she says “I”, sometimes “man”, sometimes “she”, because it’s about something from the past that is perhaps not so easy to grasp. She’s brimming with episodes; she tells what is in this folder, what she experienced – and how it felt for her. She knows how it was for her. But she doesn’t think she knows how the others experienced it.

She never saw her career as a struggle for women and equality

Sonja went to the training sessions with the women’s team from Veltheim with a small gym bag, she giggles when she talks about it. Then she chauffeured a teammate home, Stettler calls her “football mom”. She has since passed away, Sonja Stettler’s gratitude is still noticeable today, 40 years later, the “soccer mom” was caring and taught her a lot. What it means to be submissive or to show respect, but: “She never made me understand how young I was. She took me for granted.”

An attitude that women footballers in general did not necessarily feel. A newspaper article from the second half of the 1990s is stored in the yellow folder. In it, Stettler says that in the first ten years of her career, women’s football developed “very slowly”, “then there was a boom”. The reputation of the Olympic Summer Games in Atlanta in 1996 had increased, but, as Stettler was quoted in 1997: “I don’t think it can go much further.”

Anyone who talks to Stettler today gets the sense that such words conceal neither frustration nor criticism. She lived her life, and I’m sure she sometimes thought “a little more would be good too”, a little more money, which was nothing but expenses, a little more acceptance – but whether she also saw her career as a struggle for the woman to equality looked? “No.”

Different times, different countries: a poster in front of a women’s international match with Sonja Stettler, Switzerland – Yugoslavia.

She thinks very well politically, she has now completed four training courses, in retail, with the police, in KV, then in accounting and trusteeship, she has been working as a VAT auditor for many years. But in the old life she accepted the conditions as they were. Zero international matches despite international experience. An international opponent named Yugoslavia. Newspaper titles like: «Girls and women in trend». Afterwards: “Incredible, but true: since 1971 there have been girls and women from our region, from our city, who have dedicated their free time to football.”

The girl Sonja dedicated herself completely to football because she preferred a team sport to an individual sport. “You can also be weak in a team,” she says, “you don’t have to be complete, others will compensate for your weaknesses.” She was one of the outstanding Swiss players of her generation and moved to Germany to TuS Niederkirchen in the mid-1990s. And the thick folder with a remarkably large number of match reports actually shows that Stettler did not spend his career in total anonymity. There was some publicity. But publicity doesn’t have to mean respect.

On a par with Stefan Rehn, the World Cup and European Championship participant on Wikipedia and Youtube

At the beginning of 1998, during her last season, she received the award for the “best Swiss footballer of the season”, which was presented for the first time. It is “good and right that a woman has also been awarded. That’s how women’s football got a media presence.” But Stettler fundamentally questions such individual awards in a team sport.

In the yellow folder about her old life there is a picture of this award: Stettler with Stefan Rehn, the best player in the men’s league at the time, director of Lausanne. The “Tages-Anzeiger” wrote that Stettler was “the most complete, technically and athletically best Swiss footballer”. But Rehn, 45 international matches for Sweden, World Cup and European Championship participant, has Wikipedia entries in more than ten languages and many YouTube videos – nothing like Stettler.

The best in the country: Sonja Stettler, then still a weirdo, and Stefan Rehn in early 1998.

Stettler doesn’t know where the trophy for this award is, “but I don’t want to be misunderstood: I really enjoyed the time. Of course, when I meet people from the old days, you talk about the old days, and it’s funny to roll over such anecdotes. But if you only talk about football with other people who don’t know anything about football because you have the feeling: Ah, that was my time – then you’ve missed something in life.

And it went forward – to Barcelona, Chelsea, Paris Saint-Germain

Sonja Stettler was the most complete in a sport in which she participated because “you don’t have to be complete”. She was the Swiss record goalscorer for years, but at some point she was replaced and didn’t even notice. She missed it; but that she missed it means to her that she hasn’t missed anything in life. Sonja Stettler never thinks that she would have preferred to have been born 20 or 30 years later so that she would be a professional footballer today.

When she said goodbye to her previous life in 1998, she did it with full conviction. At almost 29, as nominally the best player, with a double broken jaw that she suffered in the cup final. She left the football environment, continued her education, and when asked whether it would have seemed too hopeless for her to get involved in football, Sonja Stettler says: “Maybe I just had enough of football. You say to yourself: Now you’ve always, always, always given – and now I just want to do something different. You always have to fight against hurdles, and you can’t do that with half a boost.”

But when she says that she has always given, always, always, always – she doesn’t want to say that not enough has come back. With such thoughts, Stettler thinks, she would have wasted resources unnecessarily.

At first, Sonja Stettler wanted something that didn’t even exist: to become a professional soccer player. And after that she lived football as much as a woman could at that time. As she once said: “I don’t think it can go much further forward.” But it worked. Ana Maria Crnogorcevic played with FC Barcelona at the end of March in a match that was watched by more than 90,000 spectators. Ramona Bachmann played at Chelsea and now plays at Paris Saint-Germain and has 209,000 followers on Instagram – which is no comparison to Alisha Lehmann, who is absent from the EURO but has 7.7 million followers.

91,553 spectators at Camp Nou: Barcelona – Real Madrid in the Champions League quarterfinals on March 30, 2022.

And today there are more women professional footballers than people who have walked on the moon. It’s a strange comparison because there were only twelve people on the moon. But it probably says a lot.