Tardigrades have extraordinary survival skills. They are called extremophiles, because of their ability to survive in unbearable environments. A lunar mission carried them. It crashed in 2019. Could they have survived?

On February 22, 2019, a space probe, that is to say without a crew, was placed in orbit around the Moon with the objective of landing on the moon. It was a first, because never before had a private spacecraft landed on lunar soil. Additionally, the probe carried tardigrades in a dehydrated and inactive, but viable, form.

Everything was going as planned when suddenly, on April 11, the probe experienced a problem with its propulsion as it began its descent. The speed was too great to slow down sufficiently, so it crashed into our satellite at over 3,000 km/h.

The shock was terrible and the probe dispersed over a hundred meters. We know this because the impact was photographed by NASA’s LRO (Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter) satellite.

What happened to the tardigrades? Did they survive and if so, can they colonize the Moon? Is the Moon contaminated?

Tardigrades are almost indestructible

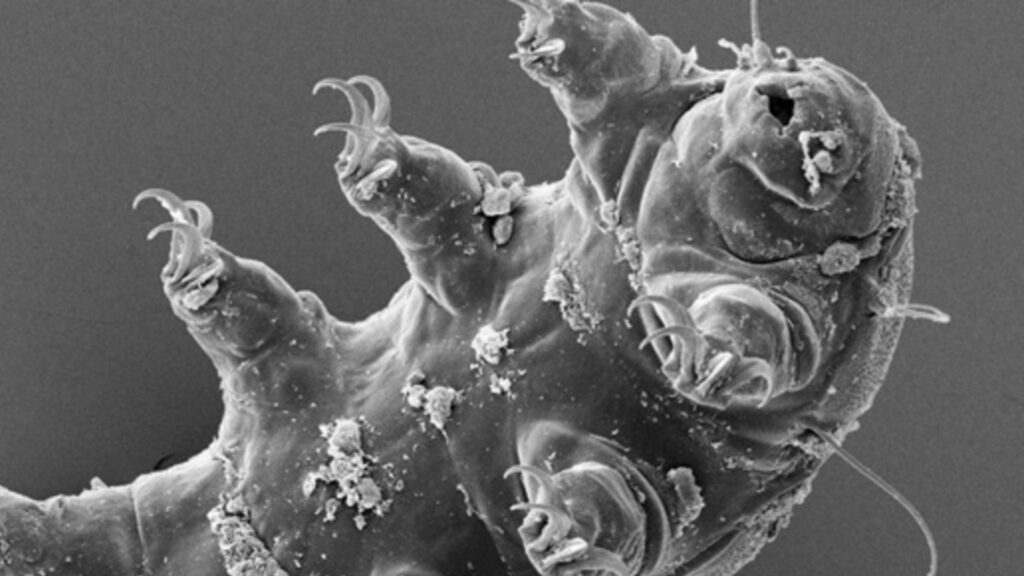

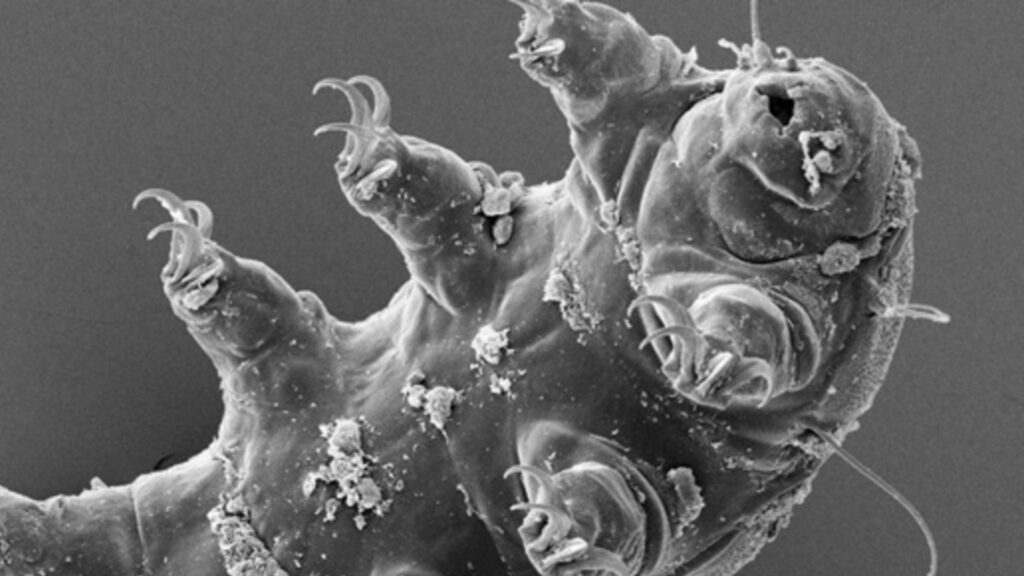

Tardigrades are microscopic animals. They are less than a millimeter long. Most have two eyes, but all have neurons, a mouth opening at the end of a retractable proboscis, an intestine containing a microbiota and four pairs of non-articulated legs ending in claws. These animals share a common ancestor with arthropods such as insects or arachnids.

The majority are found in aquatic environments, but they occupy all environments, even urban ones. Emmanuelle Delagoutte, research fellow at the CNRS, collects them from mosses and lichens in the Jardin des Plantes at the Museum in Paris. Tardigrades need to be surrounded by a film of water to remain active, feed on microalgae such as chlorella, grow, move and reproduce. They reproduce sexually or asexually via parthenogenesis, that is to say from an unfertilized egg, or hermaphroditism when an individual, which has both male and female gametes, becomes self-fertilizing. After hatching from the egg, the life of a tardigrade in active form lasts from 3 to 30 months. In total, 1,265 species have been described, including two fossils.

Tardigrades are famous for their resistance to conditions that do not exist on Earth or the Moon. They can, in fact, shut down their metabolism, in particular by losing up to 95% of their body water. Some species synthesize a sugar, trehalose, which acts as an antifreeze, others synthesize proteins which are thought to incorporate cellular constituents into an amorphous “glassy” network, thus providing resistance and protection to each cell.

Dehydration deforms the body, which can shrink in size by half. The paws disappear, only the claws are still visible. This state called cryptobiosis persists until conditions become favorable again.

However, depending on the species, individuals need more or less time to dehydrate and not all specimens of the same species manage to return to active life.

Dehydrated adults survive for a few minutes at temperatures of –272°C or 150°C, and in the long term at high doses of gamma rays of 1,000 or 4,400 Gray (Gy) depending on the species. For comparison, a dose of 10 Gy is fatal for a human and 40 to 50,000 Gy sterilizes all types of equipment. However, regardless of the dose, irradiation kills the eggs. Furthermore, the protection conferred by cryptobiosis is not always clear, as in the species Milnesium tardigradum where irradiation curiously affects both active and dehydrated animals in the same way.

Survival of tardigrades on the Moon faces several obstacles

What happened to the tardigrades after the crash? Are some still viable, buried under regolith, lunar dust whose depth varies from a few meters to a few tens of meters?

First of all, they must have survived the impact. Laboratory tests have shown that frozen specimens of the species Hypsibius dujardini were intact after an impact at 2,600 km/h under vacuum on sand, but were mutilated beyond 3,000 km/h.

They must then resist the absence of water and withstand a cold of –170 to -190°C during the lunar night and a heat of 100 to 120°C during the day. A lunar day or night lasts a long time, a little less than 15 Earth days. Even the probe was not designed to withstand such amplitudes and had to cease all activity after only a few Earth days.

Finally, the surface of the Moon is not protected from solar particles and cosmic rays, particularly gamma rays. But there, the tardigrades would be able to resist. Indeed, Robert Wimmer-Schweingruber, professor at the University of Kiel in Germany, and his team showed that the doses of gamma rays striking the lunar surface were permanent, but low compared to the doses cited previously. According to him, 10 years of exposure to gamma rays would correspond to a total dose of around 1 Gy.

Regardless, without water, oxygen or microalgae, the tardigrades will never be able to reactivate. Thus, colonization of the Moon by these animals is impossible. But specimens are on lunar soil and their presence raises ethical questions, as Matthew Silk, an ecologist at the University of Edinburgh, points out. Among these questions, there is one on the scientific level. At a time when space exploration is taking off again in all directions, will contaminating other planets make us lose the possibility of looking for extraterrestrial life?

The author warmly thanks Emmanuelle Delagoutte and Cédric Hubas of the Muséum de Paris, as well as Robert Wimmer-Schweingruber of the University of Kiel, for their critical reading of the text and their advice.

Laurent Palka, Lecturer, National Museum of Natural History (MNHN)

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Do you want to know everything about the mobility of tomorrow, from electric cars to e-bikes? Subscribe now to our Watt Else newsletter!