Contents

Crazy! A non-fiction book worth seeing shows how the car influenced the architecture of the 20th century – and continues to do so today.

There is this photo from 1964. It shows an older gentleman pulling up in his Mercedes at the drive-in counter of a bank in Zurich’s “Zur Palme” high-rise building. Spicy detail: The man gets out of his car to walk to the counter.

Legend:

He didn’t have to get out at all: an older gentleman with old reflexes in front of a Zurich bank with a “drive-in counter” that was still new at the time.

Walter Binder / gta archive / ETH Zurich, Haefeli Moser Steiger

So someone didn’t understand, smiles Eric Wegerhoff, author of the book “Automobile and Architecture,” “that he could do his business from his car.” At that time, the drive-in counter was a new type of building, created for cars, similar to motels and car washes, parking garages or motorway service stations.

A “creative conflict”

The most important influence of the car on architecture is that cars move, but buildings do not. That triggered a creative conflict, says Erik Wegerhoff, who teaches at ETH Zurich. And first: panic among architects in the early 20th century.

“People thought that this thing was on its way,” says Wegerhoff, “and not just from A to B, but into a promising future.” Architecture first had to fulfill the promise of this automotive movement. At least that’s how we saw it in the first decades of the 20th century.

New design language

Back then, the cities were narrow and not designed for the speed and space required by the new vehicle. Streets had to be created and new architectural forms emerged, such as the Mossehaus in Berlin, which Erich Mendelssohn rebuilt in a streamlined manner from 1921 onwards.

Legend:

After a renovation by Erich Mendelsohn, the Mossehaus in Berlin-Mitte is one of the model representatives of the so-called “streamline modernism”.

Jörg Zägel / Wikipedia

Or Le Corbusier’s studio house in Paris for the painter Amédée Ozenfant with a car garage that takes up almost the entire ground floor and a direct staircase up to the studio.

“This movement-oriented architecture probably had its heyday in the 1950s and early 1960s,” says Wegerhoff. During this time, a kind of modernist formal vocabulary developed. However, it was not always as theoretically sound as that of Erich Mendelsohn or Le Corbusier.

Legend:

Located in the 14th arrondissement in Paris: the home and studio designed by Le Corbusier in 1922 for the painter Amédée Ozenfant, which also includes a large garage.

Wikimedia

Architecture’s interest in automobiles noticeably diminished afterwards. Also because, in Wegerhoff’s opinion, many offices have hardly designed anything remarkable. According to Wegerhoff, the possibility of accessing cities by car has also led to “so much spatial fragmentation.” At least we are now aware of that.

This book changes your perspective

In his book, Erik Wegerhoff surveys the entire 20th century, divided into three chapters: “Acceleration,” “Switching,” and “Deceleration” – in keeping with the tenor of the respective debates.

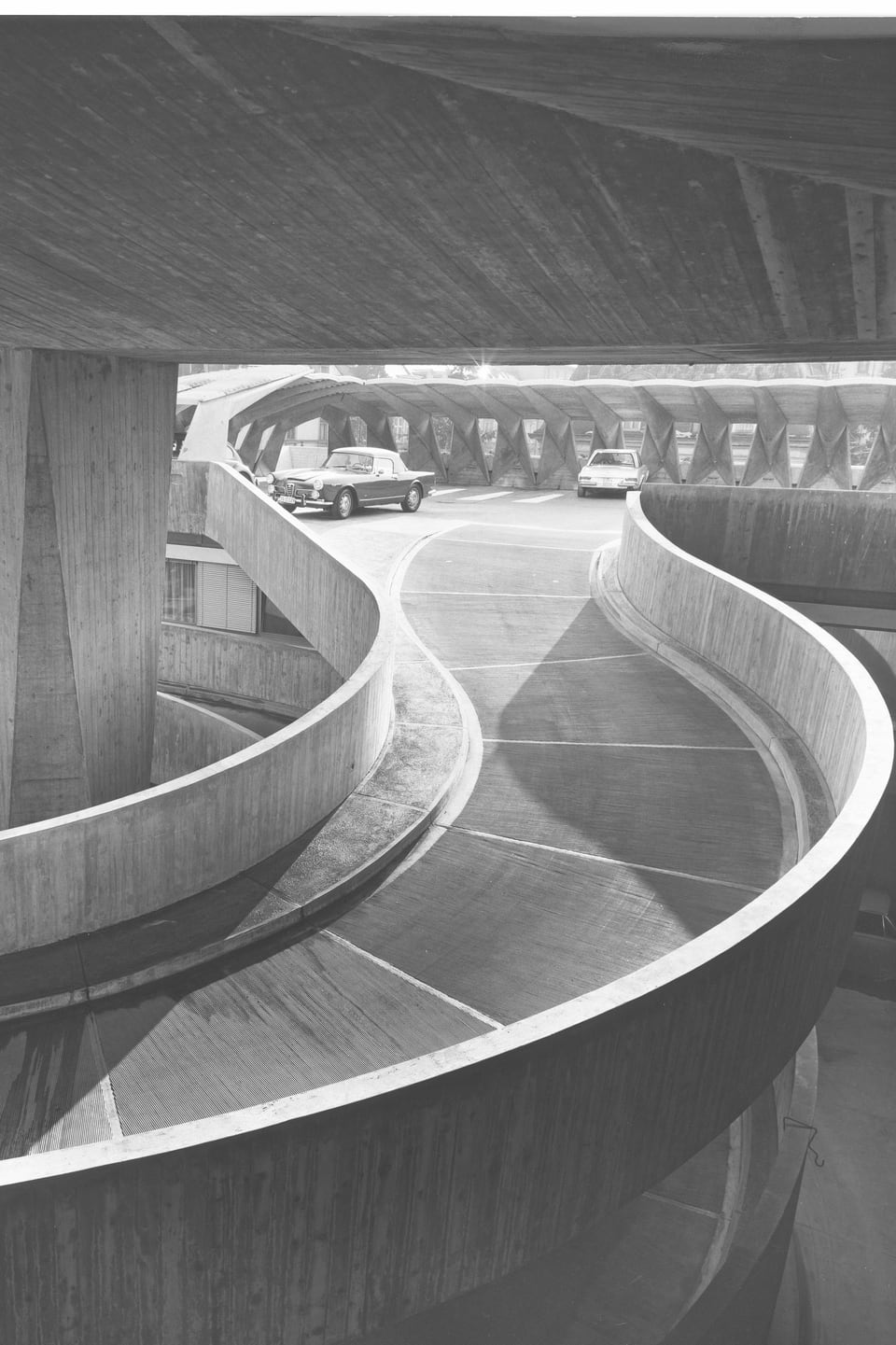

Legend:

It can look so beautiful when architecture takes a turn: the driveway to the parking deck of the Palme high-rise in Zurich-Enge, built by Haefeli Moser Steiger (1956 – 1964).

gta archive / ETH Zurich, Haefeli Moser Steiger

It all started with the speed euphoria of the 1920s and 1930s. This was followed by the invention of regulated parking spaces in the 1950s. From the 1990s onwards, criticism of automobile-centric architectural concepts became louder.

The book “Automobile and Architecture” changes the way we look out the window. Out there we see cars and streets and houses. Everyone has a lot to do with each other.