Honored at the Center Pompidou, in Paris, as part of a retrospective, Todd Haynes is also presenting his tenth film at Cannes alongside Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman. AlloCiné met him to dive into his unique universe.

1978. At only 17 years old, Todd Haynes, armed with a Super 8 camera, made his very first film, The Suicide. Lasting 20 minutes, this short film, with an unequivocal title, features a teenager who tries to open his stomach in his bathroom.

Forty-five years later, the filmmaker has become a figure in American independent cinema. Acclaimed by the greatest, from Kate Winslet to Christian Bale, the author has never stopped filming the most vulnerable, the oppressed and those who live on the margins of society.

This May 20, on the occasion of the 76th Cannes Film Festival, Todd Haynes presents, in competition, his tenth feature film, May December, worn by Julianne Moore and Natalie Portman. At the same time, in Paris, the Center Pompidou is honoring his work until May 29. The opportunity for AlloCiné to meet him to dive into his universe.

AlloCiné: Your very first short film, The Suicide, is a very striking work, which lays the first foundations of what your cinema will be. How do you make a film like that at 17?

Todd Haynes: I wrote it when I was 15. It was for a dissertation, as part of an exam. We had to write a myth about a hero and I set it in the town of Oakwood. I took a red pen, a blue pen, a black pen and a pencil. I started writing this story using the different colors, where each color corresponded to a different voice in the character’s head.

It all turned into a sort of montage that took shape. The first line of this story was in red: “And so I began to cut myself into several pieces, with care and thoroughness.” It is the fantasy of the suicide of a child, of a young boy, who is trying to cope with pain and difficulties in school. But it’s also, of course, a real metaphor for filmmaking and editing.

Screenshot “The Suicide”, Todd Haynes’ first short film in 1978.

I wanted to show that the creative process is not all rosy. You work with all kinds of feelings and you have to dig into the darkest part of yourself. And I think that’s, in part, what inspired The Suicide.

It took us two years to make it, from writing to when we finished the sound. The story is much longer, but it got pretty crazy. We ended up mixing the film in 35mm, even though we shot it in Super 8. It was an amazing experience. And that kind of sparked my ambition to do other films.

Do you remember your parents’ reaction to your film?

My dad is in the movie! He’s the one spanking my little brother. My parents have always been an integral part of my process. When I was younger, at the age of nine, I made a film on Romeo and Juliet and my father took care of the camera when I played all the roles. When I was Romeo in one shot, fighting with a sword, he was the other sword. My father has always been there, and my mother too. They supported me a lot.

You’re talking about the spanking scene. This image comes up in many of your works. Where does this obsession for this corporal punishment come from?

It was a trip down memory lane and childhood fantasies, like that dream sequence at the end of Dottie Gets Spanked [court métrage sorti en 1993, ndlr] which culminates in a sort of crazy montage. This represents a kind of orgasm. I dreamed of a spanking when I was 4 and there was an erotic component to it, I know.

Screenshot

Excerpt from “Dottie Gets Spanked” by Todd Haynes.

When I remembered this dream, my grandmother, who was into art, had all these anatomy books in her studio and I literally saw a montage of all these anatomy pictures you see in Dottie Gets Spanked. So it comes from childhood memories, but they combine with a lot of interesting ideas and thoughts that made me look into the subject of spanking.

In 1991, you made your first feature film, Poison, which follows three independent stories. Even before its release, the film is singled out by the American Family Association, a very conservative organization. They accuse you of “promoting” homosexual sexual practices. Did you see this controversy as an obstacle or rather an opportunity for your film to be more visible?

That didn’t worry me, but I wasn’t particularly interested in it bringing more attention to the film either. I wanted people to talk, ideally, about the film itself and not about the controversy. But the controversy demonstrated what the film was pointing at.

It reproduced a divided society made to isolate different people and turn them into outcasts, outsiders, problems. And you had to overcome those prejudices to get through the AIDS epidemic, because it became an opportunity to penalize and victimize people who were already marginalized by society.

We are all somehow poisoned by society.

What do you think of this new wave of puritanism that can be observed in the United States as in Europe?

There is, more than ever, a much freer hate speech and in particular expressed by the extreme right, in the United States in any case. This is a small part of our country that is getting worse. It’s just that they get a lot of attention. And of course the Trump era has contributed to this, but there are also a lot of people who are fighting back.

Voices are raised against this hatred, and I can only be optimistic. The Trump moment, even though he remains the only possible Republican candidate for president, didn’t work out. It is therefore an endangered minority that is aging within the population.

One of the major themes of your cinema deals with illness. Many of your characters are in poor health. You approach anorexia (Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story), the abuses of the chemical industries (Dark Waters), the allergies (Safe)…

There’s this idea of toxicity, poison, environmental issues, social poisoning, and that we’re all somehow poisoned by society. But what was useful and so remarkable about Jean Genet, who was the inspiration for my first film Poison, was that he was talking about the fact that we all have poison in our hearts. inside of ourselves. So the poison is not simply imposed on us.

Participant & Killer Films

In “Dark Waters”, Todd Haynes highlights the toxic drifts of the chemical company DuPont.

We also have feelings infested with poisons. We poison ourselves. There is poison when we expel all our excrement, our sputum, our urine, our pus and all the things that the body produces and we immediately say to ourselves: “Oh, that’s not part of me! It’s disgusting.“It’s a remarkable contradiction, because it’s part of us.

Of Safe To far from paradisePassing by carol, you highlight complex female characters who do not hesitate to go against the norms of society, even if it means being isolated from the rest of the world. This is also the case with your film May-December. What excites you about her heroines?

It’s hard to put them in the same category, because I see all the differences from story to story. And not all of them are necessarily powerful women. They are also vulnerable and passive or made smaller by the conditions they face. They don’t really solve the problems they face. At least that’s the case for movies like Safe And far from paradise.

These two films are worn by Julianne Moore. She’s your favorite actress. How would you describe his approach to the game?

Julianne Moore is a woman who has worked with extraordinary actors from all walks of life, but she understands the lens of the camera like no one else. She knows how to step aside to allow the viewer to enter and do her job by filling in the gaps.

May December Productions 2022 LLC

Natalie Portman and Julianne Moore in “May December”.

This is where the real emotional experience comes from and what the viewer does. And you have to give the viewer the space to do it, give them tools and sometimes take the tool away from them so they can lean more. And that’s something Julianne Moore knew intellectually and intuitively as an actress early on.

Music is very present in your work. You have made movies (Velvet Goldmine, I’m Not There…), a documentary (The Velvet Underground) on musicians and even music videos for the group Sonic Youth. What fascinates you so much in the figure of the rock star?

What I love about them, Bob Dylan and David Bowie in particular, is how they allow music, their stardom and their creativity to continue to open up questions about self and identity and to continue to trouble us in the most exciting way.

In fact, especially with the era of glam rock, which allowed young audiences and young people to feel comfortable in not knowing who they were and finding out who they were, changing, to dress a certain way and another way. This instability, this feeling of radical instability which is in fact the norm, and not the exception or the bad choice, is what these artists have continued to do.

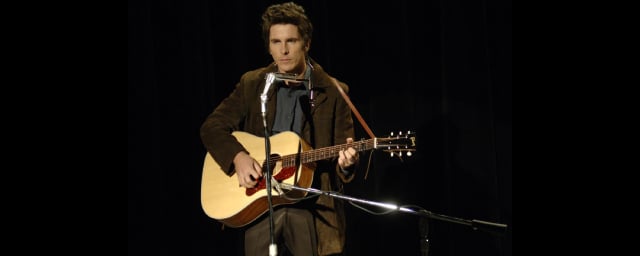

DR

Christian Bale as one of Bob Dylan’s variations on “I’m Not There.”

As for Bon Dylan, he did it out of a kind of personal necessity to keep making art. And his fans were very frustrated when he took up the electric guitar and he was no longer the folk singer, nor the protest singer. And then he tipped even further when he became a Christian again. You are completely confused by who he is and what he believes.

And in a way, that means he’s alive. Old cells die and new cells replace them. It is a constant process of mutation. He made it the guideline of his creative life.

Interview by Thomas Desroches, in Paris, May 10, 2023.

The Todd Haynes retrospective takes place at the Center Pompidou, in Paris, from May 10 to 29, 2023.