The mullahs’ regime hardly gives the opposition and the press in Iran any room to breathe. Even in Germany, unpopular people are not safe from attempts at intimidation: a Berlin journalist is threatened because he fears for his niece.

They were supposed to meet again in mid-August; the flight was already booked. But Ghazaleh Zarea was arrested in Khorramabad, western Iran, almost a month before she planned to travel to Berlin to visit her uncle. She was held in solitary confinement for 23 days and was only released after her parents put up their house as deposit. Zarea’s uncle tells all this in an interview with ntv.de.

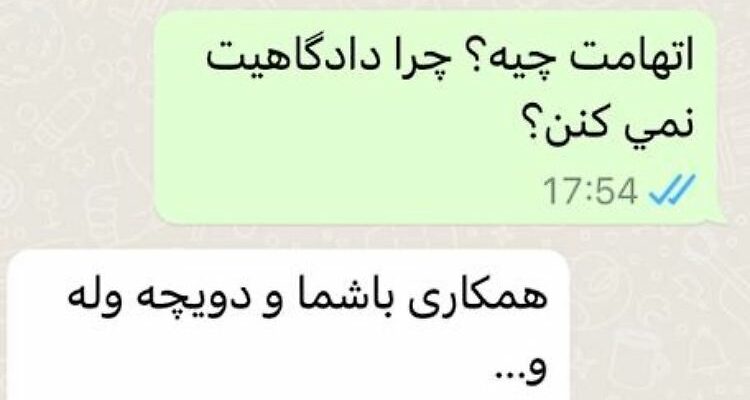

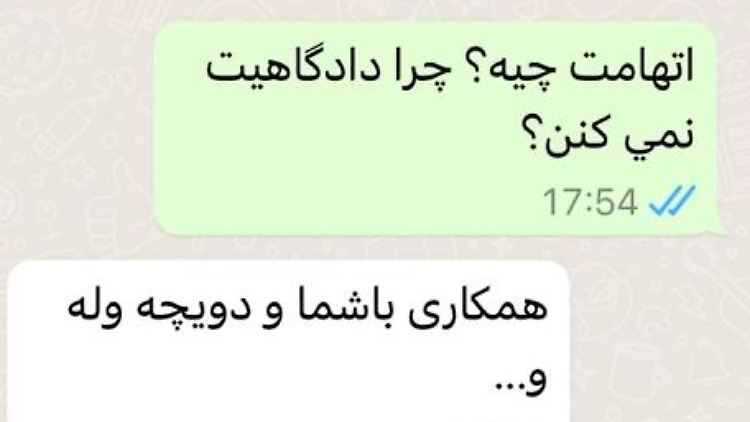

Farhad Payar speaks firmly and without much hesitation. If he is unsettled, he doesn’t show it. While his 47-year-old niece is in prison, Payar receives strange messages from her: Zarea suddenly asks for money via WhatsApp. “It was then clear to me that these were their interrogators,” says the journalist. At that moment it also became clear to him that the Iranian authorities were looking for reliable material to pin on his niece – financing from abroad, for example.

Payar continues to write to Zarea’s interrogators. They don’t identify themselves, every message begins the same: “Uncle, they know about all your activities.” “I am accused of working with you,” writes the alleged niece. “Uncle, take care of yourself,” she warns Payar. The uncle is in Germany and understands. In a dictatorship there are codes for indirect threats, says the exiled journalist.

Power grows across national borders

Payar is a handsome bald man. He has lived in Berlin since 1989, first studying political science there, then becoming a journalist and working for Deutsche Welle. In 2019 his niece visited him in Berlin. He shows her the editorial office of Deutsche Welle and they take a photo as a souvenir. She is later blamed for this: Zarea allegedly wrote from prison that her cooperation with Deutsche Welle would be her downfall. But she never wrote for Deutsche Welle and never passed on any information, says Payar. Nevertheless, Ghazaleh Zarea was sentenced to three years in prison on January 13, 2024. Among other things, because of “collaboration with anti-revolutionary networks abroad”.

Zarea can appeal the verdict. Outcome uncertain. The only thing that is certain is that his niece can now be picked up and locked up every night, says Payar. He knows that he is not to blame for his niece’s arrest and has no responsibility for her. After all, she is no longer a child, says Payar. But when he talks about her, Payar speaks more quietly, weighing his words longer. Zarea was born when he was 19, he says. He held her in his hands on the day she was born.

The Iranian regime wants people like Payar to feel responsible for the fate of their loved ones who are being vicariously harassed at home. This is how those in power exercise their influence, even across national borders. They offer incentives to remain silent and to hold back.

Again the protest is brutally repelled

When he calls Iran, Payar cannot speak openly with Zarea’s mother. The phone is probably being tapped, he says. Payar trusts that his sister understands him, that she knows he can’t do anything else. That he must observe and write about what he sees. “And you can’t see much good in Iran,” says Payar – apart from the wonderful landscape and the lovely people. It is really sad what is happening in Iran.

Payar is currently experiencing a kind of déjà vu. A wave of protests has swept through Iran again, people have risen up against the regime. And Tehran is tightening the screws, harassing and punishing people who advocate for change. This was the case in 2009, when the opposition “green movement” questioned the outcome of the presidential elections. Dozens of people died in riots and thousands were arrested.

Then again in 2022: After Jina Mahsa Amini died in police custody, there were nationwide protests. Many people in Iran smelled dawn, and the regime retaliated even more brutally. Hundreds were executed, tens of thousands were arrested and some were sentenced to years in prison.

Fear leads to isolation

Even outside the country’s borders, opponents of the regime are not safe: at the beginning of 2023, the German-Iranian exiled opposition member Jamshid Sharmahd was sentenced to death. He was apparently kidnapped from Dubai and taken to Tehran. According to the Federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution, the Iranian intelligence services are trying to spy on opposition structures in Germany, infiltrate them and intimidate their protagonists.

In this context, according to the federal government, investigations have been initiated against 24 suspected Iranian agents since 2018. But: The fear of the apartment door being cracked, people reading on Whatsapp or even physical assault leads to isolation, those affected report. The protest thus loses its effectiveness. People like Farhad Payar lose contact with their loved ones in Iran.

Already after the first major wave of protests in 2009, he felt Tehran’s anger in Berlin. An Iranian actress with whom Payar had worked ended up in prison for this. From her, Payar learned that the Iranian intelligence services also had a file on him. That’s why he hasn’t been to Iran since then, he says.

“As long as there is no good news from Iran…”

More than a decade later, Payar is once again witnessing the offshoots of a wave of Iranian protests: the regime has never targeted just one person with its punitive actions, he says. It wants to force his niece, a busy social worker, to be passive, of course. But she lives in a small town and her conviction is a warning to others. “The regime would like to see women at the stove,” says Payar. Last but not least, it is about intimidating journalists like him. However, Tehran is having the opposite effect on him personally.

Payar had remained silent about the matter until Zarea’s conviction, partly because her parents had hoped for an acquittal until the end. “Of course that doesn’t leave me indifferent,” says Payar. The arrest of his niece motivated him to take his journalistic task even more seriously and to report more. He won’t bow to the pressure.

Payar says he also made this clear to his niece’s interrogators when they communicated with him via Zarea’s cell phone. As a journalist, he is obliged to report on the events in Iran and not to invent anything or sugarcoat anything. “And as long as there is no good news from Iran, I can’t spread good news,” says Payar.

This good news cannot be expected from his niece at first. After the 2009 protests, Spiegel published “a picture of life in the Islamic Republic.” Four Iranians wrote down their worries and hopes for a week. One of them was Ghazaleh Zarea. She wrote at the time: “You can live well here as long as you don’t think.”