“The more false one seems, the further one goes. The false is the beyond. » These words are those uttered by Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud), an idle dandy, old century and Baudelairean, palabrant in the café facing the young woman, Veronika (Françoise Lebrun), with whom he has just started an affair. We are about halfway through The Mom and the Whore, a 220-minute film-river, and its author Jean Eustache seems, in this place, to have parried the main criticism that we will not fail to address to his film, among the cries of outrage that greeted him in May 1973 during its presentation at the Cannes Film Festival. Namely that it sounded fake, that people didn’t talk about it like in “real life”, but with this slight dissonance in the incarnation that transpired the rejection of professionalism.

This was to forget, as Eustache thus reminded us through the voice of his hero, that the “real” in the cinema is never more than one convention among others, and often more fabricated than the others. Through his dissonance, the Eustachian actor opens a breach into which his whole being is engulfed, and even more.

The Mom and the Whore, this black diamond of French cinema, which alone transformed the cumulative essays of the New Wave, is making a comeback on the big screen in a restored version, after thirty years of invisibility (with a few rare exceptions). A deleted scene was even reintegrated into the editing for the occasion – to tell the truth a rather anecdotal passage where the characters go to the cinema to see The Idols (1968), by Marc’O. Thus attains the status of official masterpiece for a film which for so long fueled dissensus for its extraordinary proportions, its free inspiration, its resolutely anti-modern spirit and its way of filming on the bone.

Naked and sophisticated language

The Mom and the Whore This great torrential film has remained, uprooting the fact of love from its romantic gangue, to resituate it in a magnetic field of discourse, attitudes, circulations and reversals. His characters, children of May 68 haunting Saint-Germain-des-Prés and the places of a bygone (and reviled) existentialism, think they are enjoying the fruits of sexual liberation, while coming up against archaic patterns which do not have as their ceased to govern relations between the sexes.

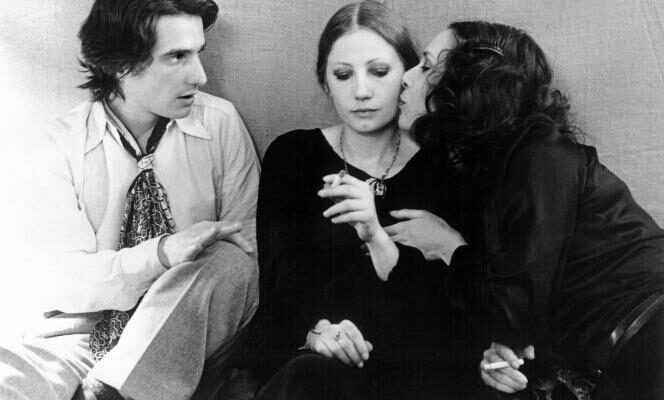

Alexandre, a penniless talker, fluttering all day long at cafe tables, between Le Flore and Les Deux Magots, shares the bed with Marie (Bernadette Lafont), who maintains it bourgeoisly, also running a clothing store. One morning, he slips away and reunites with Gilberte (a Proustian reminiscence interpreted by Isabelle Weingarten), an old girlfriend who sends him away for good.

You have 44.12% of this article left to read. The following is for subscribers only.