The German North Sea island of Helgoland is to become a center for the European hydrogen supply. The idea is controversial on the island.

Tourists on a circular hiking trail on Heligoland. The wind turbines determine the horizon.

“A hydrogen pipeline could end up here,” says Helgoland’s mayor Jörg Singer, pointing to a barrack made of white corrugated iron. He walks past a freight hall and says: “It’s already half full, but there is still room for our hydrogen business.” Finally Singer arrives at the southern harbor; Herring gulls screeching round the sky. “Yes, the federal government will renovate the jetties at the outer harbor for a three-digit million sum, so you could build up land for an LOHC terminal.” LOHC is the carrier liquid with which hydrogen is transported.

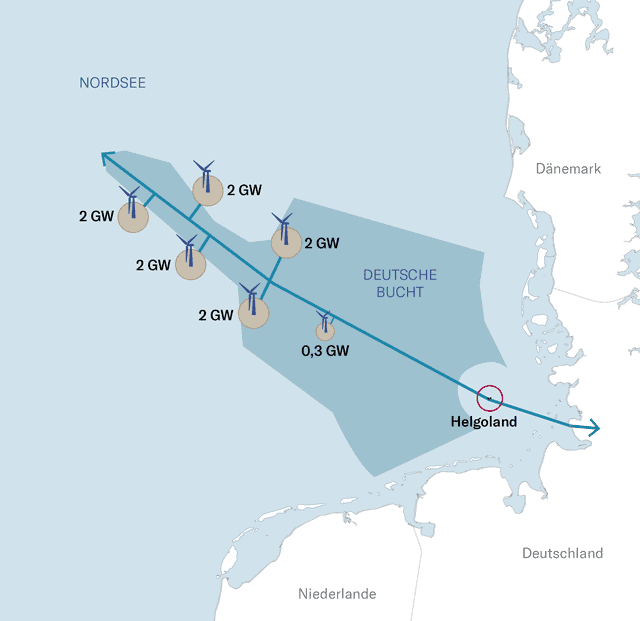

Because Helgoland – that tiny red rock in the North Sea that towers in front of the German Bight – is to become a European center of hydrogen supply. Aquaventus is the name of the project, initiated by Mayor Singer, who has already lured the wind power industry to Heligoland. With the industrial settlements he wants to rehabilitate the ailing island finances. Because they can no longer live from tourism here.

Jörg Singer is Mayor of Heligoland and sees hydrogen production as a great opportunity for the island.

The Hotel Atoll was leased by WindMW for ten years – to accommodate staff.

Jörg Singer (left) is Mayor of Heligoland and sees hydrogen production as a great opportunity for the island. The Hotel Atoll (right) was leased by WindWM for years. The company accommodates its staff there.

Green energy serves as a new business model

In the seventies, tourists still flushed plenty of money into Heligoland’s coffers. They came in droves, 800,000 a year. But Helgoland has long ceased to be the tourist magnet it was in the seventies: the number of visitors has long been halved. The island needed a new business model.

That is why Helgoland is currently changing from a holiday island to an energy island: since RWE and WindMW began to maintain and control three offshore wind farms in the North Sea from Helgoland in 2015, they have brought the island ten million euros in business tax annually. Mayor Singer used the offshore money to renovate the inland port and build apartments; the Heligoland aquarium is currently being renovated. In three years the island should be free of debt.

But if Jörg Singer has it, then that was just the beginning: Because the Aquaventus hydrogen project is much larger – it is one of the largest hydrogen projects currently planned in the world.

Over 70 European industrial companies such as RWE, Vattenfall, Ørsted, Siemens and some research companies have teamed up to turn the approximately one square kilometer island into a hydrogen giant: Hundreds of new wind turbines are to generate electricity in the sea off the island, and the electricity will generate hydrogen on site , which in turn is brought to Heligoland by pipeline. From there it goes on to the mainland by ship.

Singer – angular chin, square glasses – knows the energy industry well: He studied industrial engineering and during his first internship he helped set up wind turbines in California.

After completing his studies, he started a career in the private sector: he worked as a manager and consultant, founded or restructured companies: IT companies, pharmaceuticals and banks. Munich, Frankfurt, Hong Kong. Singer came back when the Heligoland elected him mayor. As soon as he was in office, he began to restructure the indebted island.

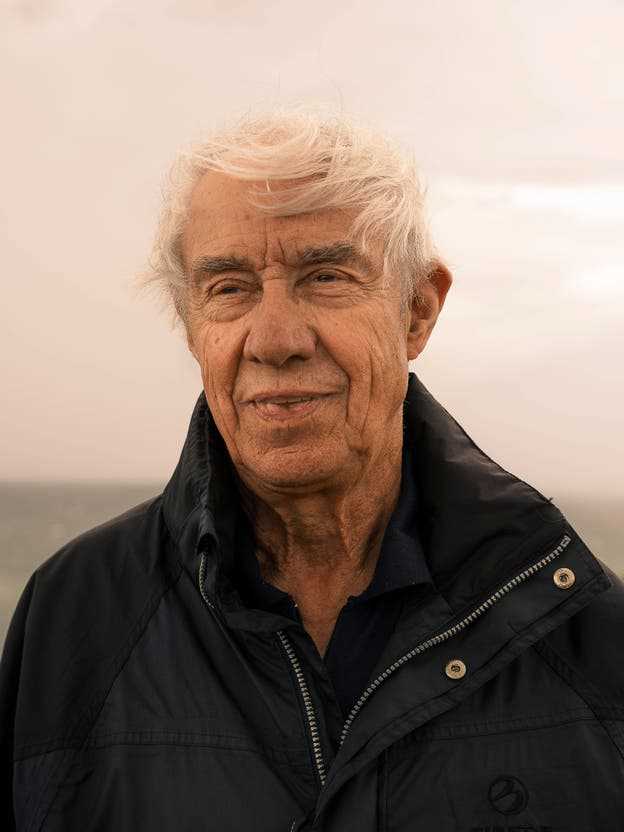

Olaf Ohlsen, born in 1935, is one of the oldest residents of Heligoland.

The nearby dune is reflected in the window of a house on Heligoland.

Olaf Ohlsen (left), born in 1935, is one of the oldest residents of Heligoland. On the right, the nearby dune is reflected in a window on Heligoland.

The operators of the wind farms have settled in the southern harbor of Heligoland. From here, the maintenance and operation of the wind farms are controlled and coordinated.

Thorsten Falke, local politician, is against the settlement of offshore and hydrogen. Heligoland is too small.

The operators of the wind farms have settled in the southern harbor of Heligoland (left). Maintenance and operation of the wind farms are coordinated from here. Local politician Thorsten Falke (right) is against the settlement of offshore and hydrogen. Heligoland is too small, he says.

There are hardly any offshore critics on Heligoland

In his office, Singer has a model of a wind turbine, through the window he looks at the Hotel Atoll, which the offshore operator WindMW has leased to accommodate the migrant workers who repair wind turbines outside Heligoland. Tourists are no longer allowed to live here. “Sure, at the beginning there were many offshore critics, but today 95 percent of the Heligoland are behind the new offshore pillar,” says Singer.

But there are many on Heligoland who are afraid that the Aquaventus hydrogen project is now a few sizes too big. One fear is that industry on the island is already disrupting tourism: a jeweler says that since the Hotel Atoll was leased to WindMW, customers have stopped coming into his shops. The owner of a clothing store says she will soon have to move to the mainland because hardly any people come to her shop to buy tax-free Adidas clothing.

Very few critics want to be quoted by name. Thorsten Falke, on the other hand, who is the third deputy mayor of Heligoland for the regional party South Schleswig Voters’ Association, also criticizes Aquaventus publicly.

The island is too small for such a project, says Falke. The chemicals that are needed to make hydrogen transportable are dangerous. And anyway: all of this could disturb the tourists because they wanted to come to a natural island and not an industrial island. “And I don’t find the migrant workers so exciting either,” he says. They already make up about a tenth of the Heligoland population.

Falke, who describes himself as an environmental politician, says: “In principle, I think hydrogen is a good idea, but not on Heligoland.”

As an environmental politician, Falke knows that hydrogen is needed to achieve the energy transition. As a local politician, he knows how much money Heligoland is already making with the energy industry. But as a Heligoland he wants to keep his island as it is.

A colony of northern gannets breed on a ledge on Heligoland.

Jochen Dierschke is the technical director of the ornithological station on Heligoland. He’s for wind power at sea – as long as animal welfare is observed.

A colony of northern gannets breed on a ledge on Heligoland. Jochen Dierschke (right) is the technical director of the ornithological station on Heligoland and advocates wind power at sea – as long as animal welfare is not neglected.

Energy transition, yes, but. . .

And then there are the birds. “Do you actually know how many birds die in wind turbines?” Asks Falke. You have to know that there are hardly any other places in Germany where there are so many birds as on Heligoland.

Nobody knows the Heligoland birds as well as Jochen Dierschke – a friendly, chain-smoking man with a messy hairstyle – who is the technical director of the ornithological station on Heligoland. He sits in the inner courtyard of the ornithological station and lists the risks: Northern gannets, which flew to Norway in search of food, would have to avoid the wind farms extensively. That costs her strength. Loons cannot fish in areas where offshore wind farms are located. That’s why they would avoid them. And thrushes, which often fly at night, can often only see the wind turbines when it is too late. Then they would be chopped up by the rotor blades. On some nights, thousands of birds could die in wind farms on the North Sea, he says.

“But please don’t get me wrong now,” says Dierschke. He is in favor of offshore wind power, and he also thinks Aquaventus is a good idea in principle. “In the long term, global warming is probably the greatest danger to people and animals,” he says, “also on Heligoland.”

The same rifts run through Heligoland as through the rest of the country: How should one decide between animal welfare and climate protection, nostalgia and progress, wind energy and homeland security? It is unclear whether the Heligoland want Aquaventus.

Would you allow a referendum to come down to it, Mr Singer?

“No, that’s cheese.”

How so?

«Because neither compromise nor consensus is possible. Nowadays it is like this: if you dare to do something, then everyone is against it. If we had held a referendum on offshore at the time, it would most likely have been rejected. We live in times when many are doing too well and the others are always supposed to change. We have to overcome that. “