The shortage of workers in Switzerland is currently unusually large. The call for wage increases is obvious. But a broad wage hike could create more new problems than solve old ones.

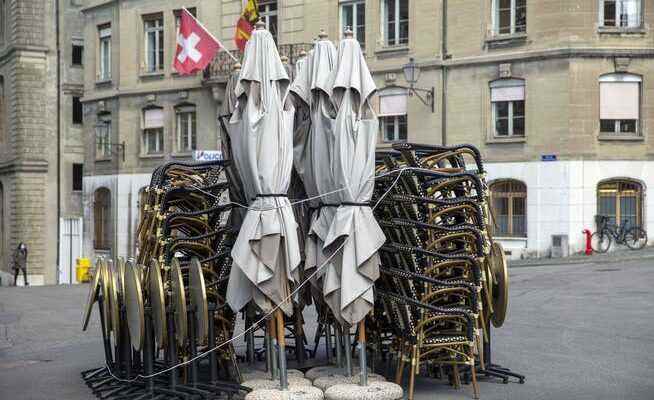

After the pandemic, many workers are again being sought in Switzerland.

The Swiss labor market digested the Corona crisis surprisingly quickly. Unemployment is now below the level of the pre-crisis year 2019. The same applies to the more broadly defined number of job seekers. And the number of people in employment exceeds the level of 2019.

But almost nothing in life is free. The strong recovery in the local labor market has also boosted immigration significantly. According to the current trend, net immigration outside of the asylum system could be over 70,000 in the current year. This means that the extent of immigration is again close to that sensitive area that led to the success of the SVP immigration initiative at the ballot box in 2014.

After all, the fear for the job is currently less virulent among many citizens than it used to be. Rather, the catchphrase of the moment is “labor shortage”. Recruitment challenges extend well beyond the usual suspects such as IT and healthcare. Carpenters and gardeners, salespeople and cooks, painters and bricklayers, teachers and logisticians are also in high demand these days. Complaints from employers about staff shortages are currently more widespread than at any time in the last twenty years.

The main factor behind this phenomenon will pass: the pent-up demand after the end of the acute phase of the corona pandemic. However, it remains to be seen whether the exceptional shortage of workers will continue for another three months or much longer. This depends not least on how severely the current energy crisis will slow down the global economy. The field is wide open here for wild speculation.

Various short-term answers are conceivable for companies with personnel concerns: increased search for personnel abroad, higher wages, acceptance of poorly qualified candidates, forgoing business opportunities, rationalization, relocation of activities abroad. Each farm will have to find its own combination.

The potential abroad is currently limited, since many companies in the EU have similar personnel concerns. However, the relatively high purchasing power of the Swiss wage level continues to make local employers attractive to EU candidates. The trend towards increased immigration is therefore likely to continue in the coming months.

The idea of a further wage increase in order to attract more domestic candidates also sounds obvious. However, the more companies act in the same spirit, the more likely it is that this will additionally fuel inflation. Economists surveyed also doubt whether a further increase in wage levels would greatly expand the supply of domestic workers. Theoretically, opposite reactions are conceivable: a higher wage tempts people to work more because the work “pays off” more, or it tempts them to reduce their hours worked because they earn enough with less work. It is unclear which effect predominates.

It is clear that many employees today are already working part-time instead of full-time without being forced to, or are taking early retirement because they can afford this luxury. However, companies can also make work more attractive in other ways: for example through more flexible working hours, more acceptance of home offices, additional creative freedom and a better working atmosphere. In some cases, this may bring more than a wage increase.

The labor market, which is currently overheating, is above all a through ball for the National Bank to get away from the distorting negative interest rates and to combat the growing risk of inflation as quickly as possible without excessive pain. When, one might ask, if not now?