Between the world wars, the poet Wilhelm Lehmann wrote a diary of his escape from the world. She had led him into nature, where he found an unbreakable order.

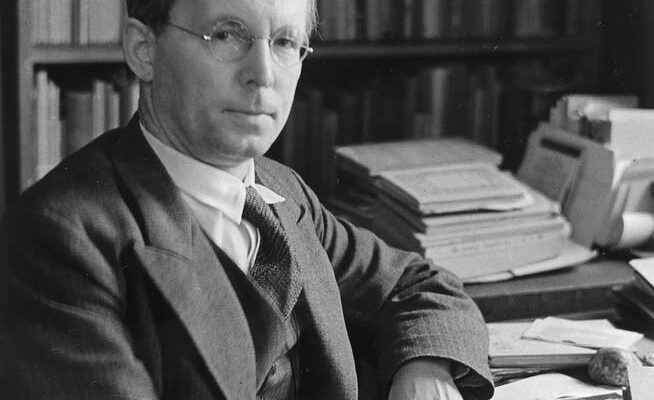

The writer Wilhelm Lehmann (1882–1968) at his favorite place to be after the great outdoors: at his desk, around 1934.

One would like to emigrate from today’s times, but where? Almost a hundred years ago, when the culture war between the right and the left was raging, the global economy was in crisis and war was in the air, Wilhelm Lehmann decided to emigrate. The German writer did not have to go far.

Out of his house and into nature. Everywhere the world collapsed, but in the coastal region of Schleswig-Holstein there was “an unfading time”. The people had nothing, but among Lehmann’s wood anemones, cranberries, broom and porst was “wealth and waste”.

Between 1927 and 1932 Wilhelm Lehmann wrote his “Bucolic Diary”, a new edition of which has just appeared and is today regarded by the growing circle of friends of nature writing as a kind of bible and not a few writers as a model. It wasn’t always like that. Lehmann was also meant when Gottfried Benn made fun of the poetic “whisperers of grasses and nuts” in the early 1950s.

Against the mess of the world

At least since then, the “Bucolic Diary” has been a kind of indicator of how much literary escape from the world is possible without feeling like you’ve ended up in kitsch. While the bombs could fall on Ukraine today and upset the ecological balance, Lehmann’s sprawling descriptions of blackbird feet scraping and reed bunting stammering seem provocative.

The serene wickerwork from the bushes of German poetry is a contrast to the chaos of the world. Everything still has its natural order here, and it is order that Wilhelm Lehmann is looking for. The First World War, in which he deserted twice, was a traumatic experience that he later overshadowed by the distance he chose to be away from civilization.

“Our world fell to pieces, we have to patch it up from the bottom up,” says Lehmann’s essay “Thanks to the Elements”. As a nature mythologist, the author writes in a kind of expressionist realism. Most of the time he is the opposite of an avant-garde, but sometimes he is. The poem «Mond im Januar» is almost concrete poetry: «I speak moon. There he levitates.»

Wilhelm Lehmann is a world flight travel guide that surrenders to the elementary events of nature in real time. It sounds like this: “The yellow, fluffy, delicate blossoms of the hedgehog’s ear have changed into hard-pronged morning stars.” “The lively, purring call of the partridges” comes from the empty fields.

Advice for birds

If you keep in mind the adjectives of the nature writer, his voluptuous willingness to use forced images, then you know where the enthusiastic Lehmann reader Peter Handke got the tone of his “different yellow noodle nests” from. Lehmann’s idyll is devoid of people or populated by generic specimens that have grown together with nature. It is said of the manager of a manor: “He moves no faster than the seed of the golden spleen herb browns, and therefore sees everything.”

Slowness is always fine with Wilhelm Lehmann, because he knows that human acceleration can lead to catastrophe. Lehmann died almost fatefully in 1968 – and was then immediately forgotten. The poet was spared the aporias of later times and a work from which illuminating passages can be sought out. With a touch of fury, the German writer wanted to warn mankind about the calamity of rationality, and there was also advice for birds: “The birds must be careful that the bitterness of the world does not tear their love apart.”

Wilhelm Lehmann. Bucolic diary. Verlag Matthes & Seitz, Berlin 2022. 280 pages, CHF 16.50.