This is 25,000 years earlier than the oldest known amputation. The archaeologists are also in this case sure that it was not an accident.

In a cave on Borneo, archaeologists have found the skeleton of a Paleolithic man whose foot was amputated and who survived.

Ideally, of course, the leg stays attached and the patient lives on. But if it has to be, doctors have a clear motto: “Life before limb”, rather saving life than limbs. However, the amputation required for this was life-threatening for most of human history. That the patient survived was rather the exception. A tomb now discovered on the Sangkulirang-Mangkalihat peninsula on Borneo in Indonesia shows that these exceptions existed.

It is the same area where arguably the world’s earliest known figurative art was found, in the form of cave paintings dating back 40,000 years. Naturally, there are hardly any human remains from this epoch, the Palaeolithic Age, let alone complete burials. The discovery of a prehistoric grave alone is spectacular. But what archaeologists from Australia and Indonesia have found in a cave and have now published in the journal “Nature” takes your breath away: the person who was buried here had the lower third of her leg amputated several years before her death – 31,000 years ago and thus around 25,000 years before the oldest known amputation.

The grave of the amputee was marked with stones

Archaeologists can tell from the layers of earth that this is an actual burial: they clearly show that the soil was worked here. In addition, several boulders are positioned over the head and arms of the deceased above the top layer of earth, apparently as a kind of grave marker.

Archaeologists determined when this tomb was created with the help of radiocarbon dating, in which the decay of the radioactive carbon isotope contained in all organisms 14C is measured. However, they did not analyze the bones themselves, but charcoal from the surrounding layers, a procedure that is quite common in archaeology. C14 dating revealed an age of 31,000 years, making it the oldest known intentional burial of a modern human in Southeast Asia.

As the individual, an anatomically modern human (Homo sapiens), died it was 19 or 20 years old, showing the development of the skeleton. However, the gender cannot be determined on the basis of the skull and pelvic bones, as is usually the case. Perhaps this will still be possible in the future, especially since all the teeth are present and intact: they contain much more information about the dead individual. The dead person lay on their back and with their knees drawn up in the grave. The right foot is complete. The one on the left is missing.

This is initially not unusual for skeletons in archaeology: it can happen that a grave is subsequently disturbed, for example if a pit is dug at this point centuries later. And of course the foot could have been severed in an accident while you were still alive. However, the archaeologists can rule out both: The clean interfaces prove that it is a matter of a targeted amputation, the scientists write. In addition, there are no examples in current clinical experience of both the fibula and the tibia being unintentionally severed.

The amputation was successful, the person lived for years

Whatever the operation necessitated, it was successful: the interfaces on the bones have healed. There is no evidence of bone inflammation, which the authors say is the most common complication of open wounds not treated with antibiotics or animal attacks such as a crocodile bite.

The person lived on for six to nine years after the operation, the scientists estimate. So at the time of the amputation she was between 10 and 14 years old. The surgeon must have had “detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the limbs and the muscle and vascular systems” in order to avoid fatal blood loss and infections. And they must have understood that the amputation was necessary for survival. People would probably have acquired this knowledge through trial and error over a long period of time. Learned through trial and error – that’s something you probably wouldn’t like to hear about a doctor’s education today.

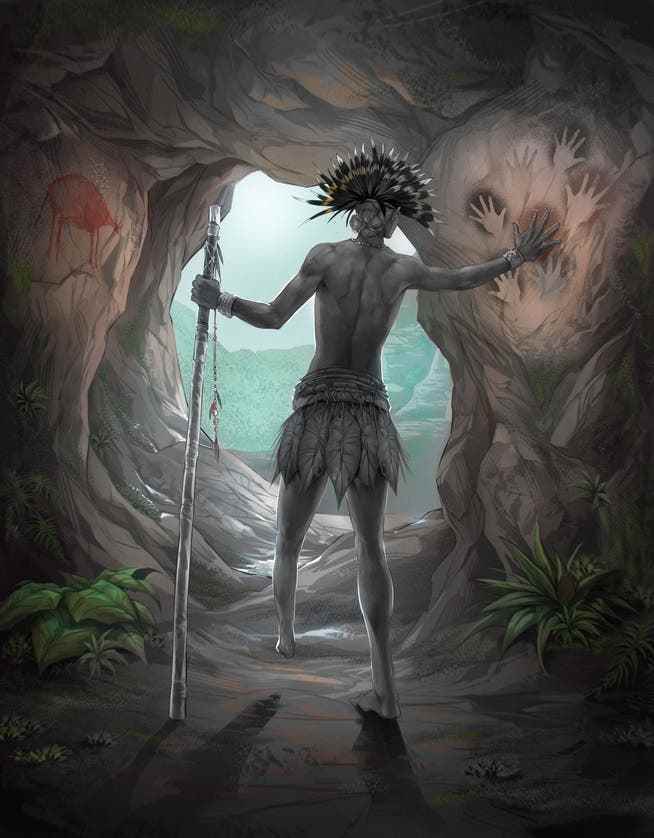

This is how an artist imagines the person with the amputated foot who lived on Borneo 31,000 years ago. The caves in the area also have numerous wall paintings from the Paleolithic period.

The amputation may have been life-saving, but life afterward was probably limited, the scientists suspect: the left leg became very thin, the muscles had probably disappeared, and the person was probably barely able to walk – one might add: at least not without a crutch .

The archaeologists also considered amputation as a punishment for their interpretation, which is still practiced today in Saudi Arabia and by Muslim extremists. However, they consider this unlikely: A person with a criminal record would probably not have been buried so carefully, they write. However, these are assumptions about the social structure at that time that cannot be proven. Likewise, one could speculate that such a punishment actually always meant death – and a person who survived it against all odds was therefore considered innocent.

Trepanations also testify to medical knowledge

The Borneo amputation is not the only example of amazing medical interventions thousands of years ago. Even on one Archaeologists want forearm amputation of Neanderthal skeleton from Iraq have observed. However, according to the authors of the Borneo study, this finding cannot be regarded as reliable. As the oldest indubitable amputation so far the case of a man who lived almost 7000 years ago, in the Neolithic period, in the area of present-day Paris in France, has been considered. Also since at least the Neolithic Age, people around the world have also practiced what is known as trepanation: they cut or drilled a hole in the skull. In at least some cases, those treated survived. The Greek physician Hippocrates, who lived from about 460 to 370 BC. Chr. lived, claimed to be able to reduce the pressure in the patient’s head and thus prevent blindness.

It is possible that sophisticated surgeries were much more common in prehistory than we now think, but the skeletons that support this simply have not survived.

The authors point out that the amputation in Borneo also meant a commitment to the patient’s environment, made even more difficult by the mobile lifestyle of the hunter-gatherers: it entailed a great deal of care, from bandaging the wound to providing food and repositioning, to avoid bed sores. Possibly, the authors write, people would have known about a herbal painkiller. A heartfelt wish goes to the 11 or 14-year-old child who underwent this operation 31,000 years ago.