ReportingDivorce with Europe consummated, the Jersey authorities have decided to restrict access to their territorial waters. In the Channel ports, fishing professionals protest against these Anglo-Norman neighbors “less and less Norman, more and more English”.

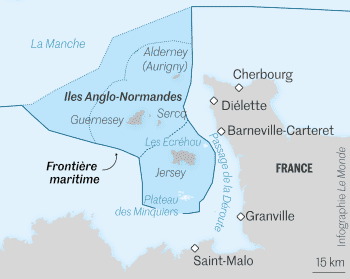

The merry-go-round is perfectly well established. Every day, at a rising tide, the boats line up in single file at the mouth of the channel. The boaters slip away to take shelter in the basin, at the end of the port of Barneville-Carteret (Manche). The fishing professionals, for their part, dock in the channel, to unload their catch of the day without delay: whelks, spiders and lobsters for the caseyers, scallops for the trawlers. Behind them, about twenty kilometers away (or 12 nautical miles), appear the Jersey coasts, towards the setting sun. A permanent sentinel, barely visible on foggy or heavy weather days, so present on any other occasion.

On the quayside, in calm weather, French and Jersey fishermen mingle, sometimes appreciate each other, often frequent the same establishments. “We all know each other”, they say. There are about fifteen fishing boats for about forty fishermen in Carteret, hardly more on the other side. We are there between neighbors, between “Norman cousins”, according to the expression politely used by the Prime Minister of Jersey, John Le Fondré, Friday, September 24, at the end of the seventh edition of the annual Summit of the Channel Islands-Manche-Normandy, largely devoted to the conflict which opposes since for months the fishermen of both sides. Because, between cousins-neighbors, the time would rather be of disagreement. Helping Brexit, a solid family quarrel has permanently settled on both sides of the passage of the Déroute.

The 160,000 inhabitants of the Channel Islands did not vote in the referendum in June 2016, but the divorce pronounced by the British prompted them to review the conditions of access to their waters, which are known to be full of fish. Also, in May, when the Jersey government decided to make the renewal of fishing licenses conditional on the provision of recent “proof of activity” in their territorial waters, French sailors saw red. How to provide these certificates after the fact, worried the owners of the smallest boats, not always equipped with the latest tracking technologies? How can the recent purchase of a boat be financed if the rules set by the Granville agreements in 2000 change suddenly, other fishermen wondered? How, finally, to exercise its activity if the authorized fishing zone had to stop so close to the French coasts, less than 4 nautical miles from Carteret, where the territorial waters of the Ecréhou begin, a string of islands and pebbles under the authority of the Bailiwick of Jersey?

You have 77.14% of this article left to read. The rest is for subscribers only.