Paralyzed people can only tweet about their thoughts or move robotic arms, researchers guess the PINs of strangers through their brain activities, monkeys play a kind of “mind pong”. Brain-computer interfaces make it possible for users to control computers with their brain waves in the form of electrical fields. Such brain-computer interfaces (BCI) are moving from the research area into practical applications, for example in the areas of medicine, virtual reality and gaming. However, lawyers warn of the massive dangers associated with this for fundamental rights and regulatory loopholes.

There are some useful BCI fields of application beyond medicine, explained Carolin Kemper, speaker at the German Research Institute for Public Administration in Speyer, at the online hacker conference rC3 (remote Chaos Communication Congress). Headsets are now available for consumers to measure the electrical activity of the brain. In principle, electroencephalography (EEG) is used, which works with electrodes on the scalp. In gaming, for example, according to Kemper, you can tell whether someone is bored, concentrated or overwhelmed. In the workplace, technology can help avoid stressful states and optimize concentration.

Elon Musk, who is working on BCI implants with his startup Neuralink, even considers it necessary to merge with artificial intelligence (AI), reported the lawyer. Otherwise, humans could no longer outdo the learning machine. This is strongly reminiscent of the utopias and dystopias of the early cyberpunk movement, where a lot revolved around uploading consciousness and exporting the soul to USB sticks and the like.

Manipulation and identity change

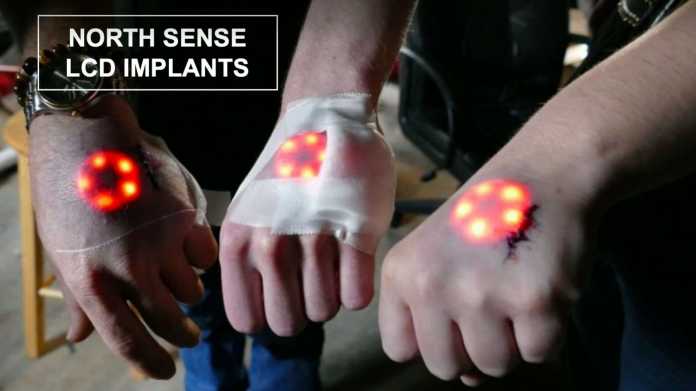

On the other hand, the technology is extremely dangerous, Kemper pointed out. Researchers had shown as early as 2019 that a blinking GIF alone could cause damage to epilepsy patients. In principle, BCIs are suitable for manipulating people, changing their identity and possibly driving them insane. Malicious apps could tap measured values and thus particularly sensitive personal data from headsets via programming interfaces. It is only a matter of time before ransomware hits medical devices such as implants. The Federal Office for Information Security (BSI) and researchers have already “found one or two knockers” with such devices.

The human brain has grown over thousands of years, so interventions are extremely dangerous, added Kemper’s colleague Michael Kolain. The consequences would not be foreseeable if there were massive use of brain implants. Researchers like Markus Gabriel also emphasized, contrary to the vision of transhumanists, that humans cannot be represented as personality with brain waves.

The legal scholar opposed the Basic Law and principles of neuroethics to BCI. The state therefore has a duty to protect the inviolable dignity of human beings and must guarantee autonomy and the free development of personality. It is incompatible with this, for example, to withdraw assistance systems from patients, exert sublime influence, launch denial-of-service attacks on relevant devices or drain their batteries. Ownership could also be affected if implants became part of one’s own body.

Basic ethics problems

In order to protect privacy, the Federal Constitutional Court of Kolain has also drawn up a series of requirements that ranged from informational self-determination to basic IT rights relating to the confidentiality and integrity of computers. A “certain basic trust” must be ensured that IT devices are not influenced from outside. The spying of data, identity theft, surveillance and extortion stand in the way of this.

But brain-computer interfaces raise new legal questions and ethical discussions, the researcher clarified. Corresponding devices often fell through the previous regulatory framework. For example, IT security law is too specific to take effect. The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in turn only affects processors of personal information and not the manufacturers of relevant products.

The EEG headset manufacturer Emotiv, for example, only has to adhere to the GDPR if it processes brain data with an app, Kemper gave an example. Only then, for example, would it be absolutely necessary to secure the state-of-the-art technology with encryption and the like. Furthermore, Emotiv emphasizes that it will not sell the devices for medical applications. The company remains outside the EU Medical Device Regulation (MVPO). BCIs also did not fall under the BSI Act.

The lawyer explained that the new law on the sale of goods in the German Civil Code (BGB), which will come into force at the beginning of 2022, will apply. So there is an update obligation, privacy-by-design must be taken into account. However, many of the terms associated with the reform are vague, so that they first have to be interpreted by the courts. Should the EU committees agree on the planned AI rules, brain implants and EEG headsets with a “stimulating” effect would be classified as high-risk systems and would have to take special precautions in terms of cybersecurity. So there are some regulatory approaches, but none of them cover everything properly.

(jk)