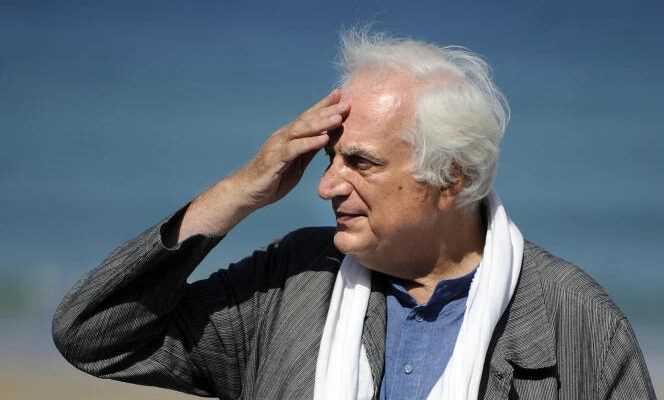

You cannot be from Lyon and not love good food, the one that devours itself with an ogre appetite and the conviviality of a troop. The multicésarized filmmaker Bertrand Tavernier, who was born there on April 25, 1941, did not betray, doing justice to this food that he swallowed, as he ate life and films. Faithful to his city – where he shot his first feature film The Watchmaker of Saint-Paul (1974) and where he chaired the Lumière Institute -, to the origins, to the culture inherited from the ancients, to friends, he had perhaps reached satiety, as we like to believe. Breathless.

This breath of which tuberculosis dispossessed him from an early age, sending the boy to the sanatorium, and on which he never ceased to take his revenge. Not very inclined to lukewarmness, Bertrand Tavernier was not a man of infatuation and nervousness but of passions and anger. Which made its voice heard when it came to denouncing torture during the Algerian war, to defend the legalization of undocumented migrants, to fight the National Front and the bad fate reserved for the suburbs. Also militant for the French cultural exception, the fight for the respect of the rights of the authors.

The big mouth – and signature – of French cinema died Thursday March 25 at the age of 79, announced the Institut Lumière in Lyon, of which he was the president.

Commitment, a family affair. More precisely a heritage from the father, René Tavernier, writer and literary critic who resisted by founding the review Confluences in which he published, under the Occupation, Paul Eluard and Louis Aragon. The latter found, with Elsa Triolet, shelter in the Tavernier villa in Lyon.

It was for Geneviève, Bertrand’s mother, that he would have written his poem there is no happy love. Bertrand, the couple’s first child, born in bourgeois comfort and the noise of the bombings, in the shadow of a Gaullist father with whom we will have to break up, one day or another. What he will do. “My father squandered his talent. I did a lot of things to differentiate myself from him: I work a lot, I don’t like dinners in town ”, he confided in March 1999 to Release.

Crazy about literature, jazz, blues and cinema

Bertrand Tavernier will therefore choose cinema – ” an unconscious way of separating myself from my father and having my own domain ”- and will be all his life viscerally left. Quick to disobey and get angry. Even if it means directing it against the Socialists, whose policy he considers too cautious.

Poor management by the father, in fact, is causing the magazine to collapse Confluences and forced the family to abandon Lyon for Paris where the little Tavernier was sent to boarding school at the Saint-Martin-de-France school in Pontoise, which was run by the Oratorians congregation. From these years, Tavernier will keep the memory of “Sadism of gym teachers” and humiliation. Not very athletic, the child finds refuge in books of which he makes excessive use. His temperament is so made that he is never an amateur but mad about … literature, and later, jazz, blues and cinema.

Tavernier refutes the chapels and claims his admiration for classicism, French quality, heir to the Renoir, Duvivier, Autant-Lara

The seventh art, the other great affair of his life, occupied him very young. A student in Paris, at the Lycée Henri IV then at the Sorbonne, he attended the film library where he founded, with the future programmer and curator Bernard Martinand and the poet Yves Martin, the Nickelodéon film club.. Place where the three friends intend to rehabilitate the American cinema of the 1940s and 1950s which no longer appeared in theaters.

From the cinema, Bertrand Tavernier loves everything. Polar, science fiction, western, musical, big and small movies. He refutes the chapels and claims his admiration for classicism, French quality, heir to the Renoir, Duvivier, Autant-Lara. It is not the struggle of the New Wave filmmakers (Truffaut, Godard, Rivette, Rohmer…) who have to settle their scores with those of the previous generation. He is one of those who take cinema as a whole. He notes, beyond the flaws, the merits that each film has, whatever the genre to which it belongs and the form it takes.

Unlimited curiosity

This enthusiasm which carries him to boundless curiosity, he transmits by writing in many specialized journals (the student newspaper L’Etrave, French Letters, the Cinema notebooks, Positive) then as press attaché for the French producer Georges de Beauregard thanks to whom Bertrand Tavernier produced two sketches for The kisses in 1963 and Luck and love in 1964.

Ten years pass during which he tirelessly promotes films forgotten or shunned by critics and writes screenplays for filmmakers Riccardo Freda and Jean Leduc, before managing to shoot his first feature film in 1974, The Watchmaker of Saint-Paul. To co-write with him the screenplay for the adaptation of Georges Simenon’s novel, The Everton Watchmaker, he calls on Jean Aurenche and Pierre Bost, the very people that François Truffaut had violently pointed out in his January 1954 article, “Une certain tendency du cinéma français”.

The novel situates the intrigue in the United States, the film transports it to Lyon, a city with a bourgeois and closed reputation from which Tavernier wishes to render another image, just as true. That of the corks where pig’s trotters, charcuterie and Beaujolais are celebrated, that of “Apartments with very high ceilings, courtyards where you can hear children playing scales “. This atmosphere, in short, so dear to Simenon as it was to Claude Chabrol, himself a good eater and a great admirer of the writer.

The theme of the filial relationship

The Watchmaker of Saint-Paul, it is also the incomprehension then the meeting between a father (Philippe Noiret who will long be the “autobiographical actor” of Tavernier) and his son (Sylvain Rougerie) accused of the murder of a man. Less than the investigation, the filial relationship (stretched before the reconciliation) is the real subject of the film. The theme will cross many other films of the filmmaker (Sunday in the countryside, 1984; Nostalgia daddy, 1990 ; The Princess of Montpensier, 2010, among others), like a work constantly put back on the workbench to refine it, correct it, repair it from its imperfections, understand it.

Bertrand Tavernier is an earthling steeped in culture who observes, understands what surrounds him, listens to the concerns of his contemporaries and revisits the past to understand the present.

Because Bertrand Tavernier is a craftsman who loves a job well done to the point of being sometimes criticized for his academicism. An earthling steeped in culture who observes, understands what surrounds him, listens to the concerns of his contemporaries and revisits the past to apprehend the present. He makes it the subject of his films, as his indignation arises.

As evidenced by Spoiled children (1977), where a director (Michel Piccoli) joins the neighbors of his building in their fight against the abusive methods of the owner, or even It starts today (1999), plunged into social misery through the daily life of a nursery school director in the north of France.

He is also moved, in a striking and premonitory way, by the excesses of voyeurism that television encourages in Death Live (1980) with Romy Schneider. And never ceases to question violence, a subject that fascinates him and provides his darkest films. Among them : L.627 released in 1992, a very documented chronicle on a small police force specializing in the fight against drugs that the lack of material means leads to moral and social decay. And The Bait (1995), portrait of three young people trapped by the taste for appearance, prisoners of the illusion of easy money, and whose lack of culture and a lack of benchmarks lead to commit two sordid crimes.

Voracity and eclecticism

Bertrand Tavernier practices cinema as he discovered and defended it. Voraciously – he shoots almost a film a year – and eclecticism, walking with varying degrees of success from one genre to another. Thrillers and films in costume (Let the party begin, 1975; The Judge and the Assassin, 1976; Life and nothing else, 1989; Captain Conan, 1996; Pass, 2002; The Princess of Montpensier, 2010) largely feed his work.

But not only. With Wipe (1981), a tragic fable about a humanity floundering in all vices, the filmmaker allows himself a violent satire on colonialism and racism. With Around midnight (1986), he signs his musical film and his homage to jazz, and agrees with The Beatrice Passion (1987) a medieval fresco. Finally, in 2009, he made his first and only American experience, and signed a metaphysical thriller by adapting the novel by James Lee Burke In the electric haze with the Confederate dead starring Tommy Lee Jones.

His love of cinema is also reflected in several books. In particular a monumental book of a thousand pages American Friends (Institut Lumière-Actes Sud, 1993, augmented reprint 2008) which brings together the interviews carried out over half a century by Bertrand Tavernier with Hollywood greats (John Huston, Elia Kazan, Robert Altman, etc.); and a collection of memories gathered by Noël Simsolo in Cinema in the blood (Writing, 2011).

With the same concern for sharing, he realized at the age of 75 Journey through French cinema (2016), a documentary of more than three hours in which the director looks back on his life through the many films he loves.

The documentary deepens his thinking, extends his commitments, denounces as much as it sheds light on what angers him. The format provides an ideal framework for his protests. He adopts it to return to the Algerian war and signs with Patrick Rotman The Nameless War, where those who have always been silent testify. He used it in 2001 to affirm his support for those called the “Double penalty” (because they were sentenced to prison before being deported to their country): Stories of broken lives, co-directed with his son Nils Tavernier.

Father also of a daughter, the novelist Tiffany Tavernier, the filmmaker has always remained discreet about his private life. This great shy talker who hated looking at himself, analyzing himself and talking about himself, preferred to direct his attention – and that of others – towards those humans whom suffering had not spared, these strangers whose secrets, never ceasing. never intrigue him, have watered his films.

Bertrand Tavernier in a few dates

April 25, 1941 Born in Lyon

1974 “The Watchmaker of Saint-Paul”

1975 ” Let the party begin “

1976 “The Judge and the Assassin”

nineteen eighty one ” Wipe “

1984 “A Sunday in the countryside”

1989 “Life and nothing else”

1993 Publishes “American Friends”

2016 “Journey through French cinema”, documentary

2021 Died at the age of 79