At the 1952 Olympic Games, Emil Zatopek managed the feat of winning gold in the 5,000 meters, 10,000 meters and the marathon. But the Czech also left a political legacy. Because of his bravery, he lost privileges.

The miracle runner Emil Zatopek’s recipe for success? Be simple in everything you do.

His style was unmistakable: head thrown back, tongue out and snarling like a locomotive. So Emil Zatopek did his rounds, stomping and wildly flailing his arms. Everything about his movements was reminiscent of out-of-control, painful mechanics—and that running was a martial art for him.

As the seventh child of a poor carpenter, Zatopek had to struggle through life. He once said: “I had to overcome an inferiority complex, and its compensation is nicer than strong muscles.”

At first he toiled away at a meager salary for a shoe manufacturer in the rubber production

Indicative of Zatopek’s attitude to the sport is the role model he had: an American named Glenn Cunningham, who won the silver medal in the 1500 meters at the 1936 Berlin Olympics. Cunningham was in a serious accident when he was eight years old and has been disabled ever since. A teacher got the boy into sports for therapeutic reasons, and Cunningham’s tenacity paid off. For Zatopek, this was proof that you can surpass yourself.

Runner and philanthropist Emil Zatopek was born on September 19, 1922 in the Moravian provincial town of Koprivnice. At the age of fifteen his father sent him to be an apprentice to the shoe manufacturer Bata. There he toiled with meager salary at first in the rubber production.

When Bata was looking for a sporty advertising medium for his shoes in 1941, Zatopek’s hour struck. The boss sentenced the slim boy to take part in a race in Zlin, which was attended by all of the country’s running elite. Because he didn’t want any trouble with the master, he reluctantly started – and surprisingly finished second.

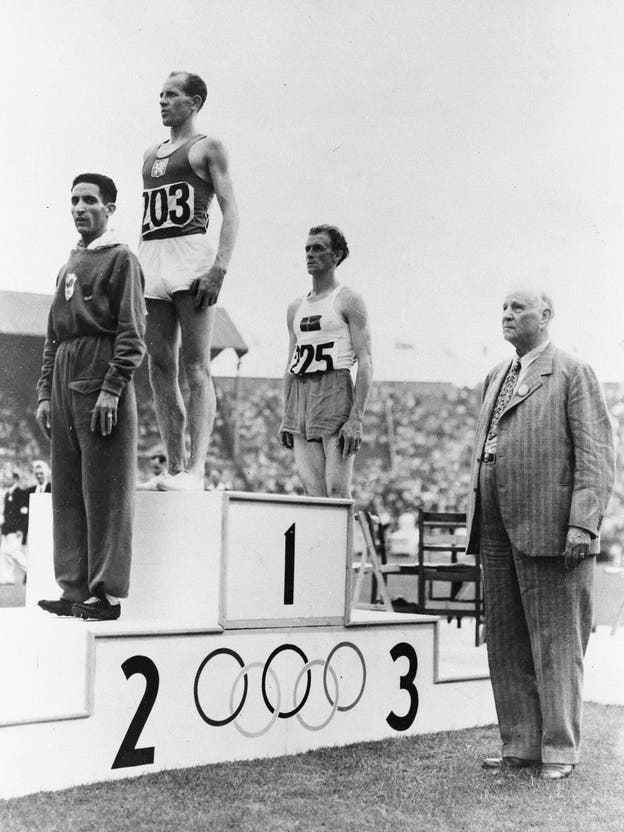

This was the beginning of the unprecedented rise of the autodidact Zatopek. Seven years later, the “Bata Man” won gold in the 10,000 meters at the Olympic Games in London. The basis of his success was that he took extensive interval training to a new level. And he had a simple recipe for success: just listen to yourself, let others do the talking and just run, with passion and serenity. And above all: Be simple in everything you do.

In 1948, Emil Zatopek won Olympic gold in the 10,000 meters at Wembley.

Extensive interval training took Emil Zatopek (second from left) to a new level.

The fact that he did thirty or even forty 400-meter sprints a day with only short breaks in training makes one shiver with admiration to this day. At the peak of his career, Zatopek reaped the rewards of that drudgery. He became Olympic champion three times in Helsinki in 1952: he triumphed over 5,000 meters and 10,000 meters, and with his first marathon he downright outclassed his competitors.

But Zatopek almost didn’t go to the games in the Finnish capital because of differences of opinion with the party officials. They didn’t want to take his training colleague Stanislav Jungwirth to Helsinki because his father had been critical of the Communist Party. Zatopek threatened a boycott. The party officials had to give way. Jungwirth was allowed to travel. A triumph for Zatopek.

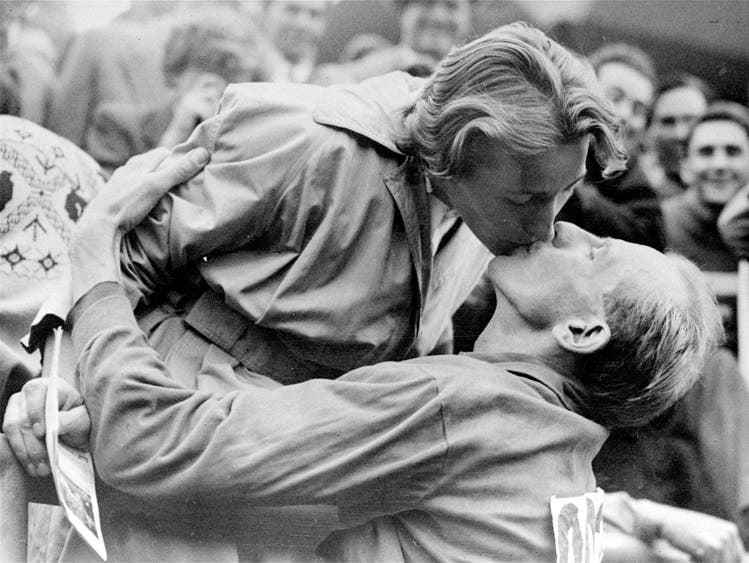

But when he spoke all too clearly for socialism with a human face in the Prague Spring of 1968, the powerful no longer showed any reluctance to bite. A picture of Zatopek went around the world: after Russian troops invaded Czechoslovakia, the sports idol clumsily but resolutely climbed onto a tank and called on the occupying forces to withdraw. The figurehead of socialism was now the target. His courage and sincerity cost him his privileges.

He disappeared for years as a laborer in the Jachymov uranium mine

Emil Zatopek was as uncompromising in his moral attitude as in sports. He was expelled from the party and the military and disappeared for years as a laborer in the Jachymov uranium mine. Zatopek endured all the reprisals, such as having his name removed from school textbooks or having the stadium named after him in Houstka renamed back to him, with the same stoic tenacity that had distinguished him on the arena.

In 1972, Willi Daume, President of Germany’s National Olympic Committee, brought him back into the public eye. He invited Zatopek to the Munich Olympics. The party let Zatopek travel. But Zatopek would not have been Zatopek if he had not also stood up for other outlaws, such as Vera Caslavska. The seven-time Olympic gymnastics champion was spokesman for the “Manifesto of 2000 Words” (“Be the master in your own country”) in 1968. Zatopek only wanted to go to Munich with her.

In 1990 he registered with quiet satisfaction the success of the Velvet Revolution and the democratization of Czechoslovakia. A late victory – perhaps the most important in his life. Zatopek’s sporting ambitions have always been closely linked to the social and political fortunes of his country. This is exactly why the exceptional runner is so popular across all borders and generations, more than twenty years after his death.