The queue to take advantage of a ticket to space continues to lengthen in Europe. Since Soyuz is no longer an option since the invasion of Ukraine, satellites and probes wait Ariadne 6. The Euclid telescope, in particular, could remain stuck on the ground for almost two more years.

The astrophysicists see their project completed, but at a standstill.

Do without Soyuz

Compared to the numerous Russian announcements or threats regarding the future of the International Space Station, the sanctions and counter-sanctions concerning the Soyuz launchers sent from the Guiana Space Center (CSG) have been somewhat forgotten. Indeed, two days after the invasion of Ukraine, Roscosmos announced the repatriation of its teams who were in Guyana as well as the end of the takeoffs of the iconic Russian launcher

Immediately, European officials said they were looking for alternatives, but six months later these have yet to materialize. Several Soyuz launches were planned from the CSG this year, in particular within the framework of the Galileo program (two pairs of satellites), but also in the service of the French defense with the “spy” satellite CSO-3… Others were also planned for 2023, in particular in collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA) to send the earth observation satellite EarthCare, the radar satellite Sentinel-1C, and the galaxy observer telescope, Euclid. Since February, both in public and behind the scenes, each team has been looking for the least penalizing solution.

Ariane 6 is still absent

The options for sending a telescope like Euclid into orbit are few, however. Already, a change of launcher implies additional work, because the flight profile and the associated constraints (vibrations, firing duration, ejection point to reach the Earth-Sun L2 Lagrange point) will change.

In reality, if the ESA sticks to its own specifications, it must use a European launcher, that is to say Ariane 6. With one problem: the rocket is not available today, any more than it will be in time to replace Soyuz. The maiden lift-off of Ariane 6 is now more or less scheduled for the first half of 2023. No precise date has been announced, institutions and manufacturers are awaiting the results of the current campaign of combined tests which will last several more month. And even so, do not expect a crowd of takeoffs from the new launcher in its first year of operation. Even if Ariane 6 is eagerly awaited and everything goes well for its inaugural launch (the teams are working on it, but it is not guaranteed), it will take time to get into cruising speed.

A heavy scientific record

Euclid’s scientific teams were therefore faced with an agenda that initially seemed impossible to them: they must prepare for takeoff of their vehicle by the end of the year… 2024. And this, while it has been sold out since the summer of 2022, in the premises of Thales Alenia Space in Cannes! This postponement of more than 18 months goes badly, already because it results in a big budget overrun. The telescope itself is indeed finished, so it will have to be mothballed, in impeccable conditions, which costs a fortune (we are talking about between 5 and 7 million euros per month, i.e. practically 100 million euros of storage before sending to Guyana). There is also the scientific impact of the teams and positions that will have to be reformed, with many laboratories operating on fixed-term contracts (particularly among doctoral and post-doctoral students), not to mention the inevitable grant application files funds.

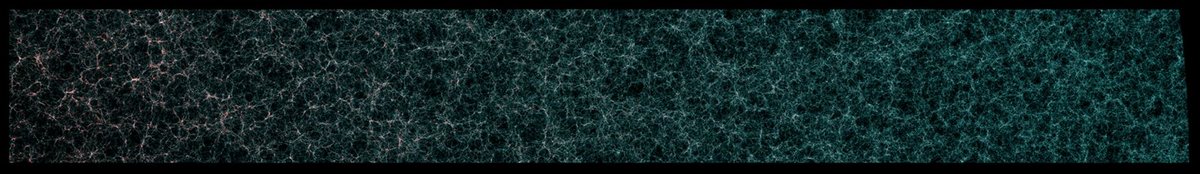

Moreover, the teams hoped to be operational before the Americans. Euclid is theoretically an incredible instrument, capable of achieving on the scale of galaxies what the Gaia mission accomplishes for the stars in our vicinity. It would make it possible to constitute a formidable catalog of galaxies, clusters, their shape, their age, their spectrum, etc. with in particular a prestigious scientific objective, to use these data to understand the acceleration of the Universe and to decipher the role of dark energy.

In 2026-27, the United States will (if all goes well) send its new Nancy Grace Roman Telescope (NGR) into orbit, and it too will have capabilities in this area, albeit with complementary measurements. So that they can work in tandem (and not in competition), it is important that the Euclid data is already available when the NGR begins its mission… Even if it is possible that the American telescope will also suffer from delays.

Not on top of the pile

Finally, and despite requests to the ESA, Euclid does not seem to become a priority file. The European Union is already pressing the agency for other satellites. The next Galileo units must be sent into orbit as well as Sentinel-1C, which will replace the 1B radar unit which has definitely broken down this year. The French State is pushing for its part to complete the deployment of its CSO constellation, highly prized military optical observation while the war is raging less than 2,000 km from our borders.

For some scientists, ESA’s commitment to only wanting to use European launchers is more stubborn than a sovereignty issue: Ariane 6 is costing them years of delay. Some even fear that Arianespace, faced with deadlines, will put the needs of its flagship customer for years to come, Amazon, ahead of those of their telescope. It should be noted that for ESA, and even more for its member countries very involved in launchers (France, Germany or Italy), the alternative makes people cringe, because it is almost always SpaceX that comes back on the table.

Indeed, the international market is in tension. Without Russia, ESA could turn to India, but the country has its own problems in the launcher sector (rhythm and reliability). Japan, too, is transitioning to its next generation Ariane 6 competitor H-3, and other US partners either don’t have the appropriate rockets or have full schedules for several years. And the European NewSpace sector, for its part, should not be there soon enough.

The American option

So what to do? ESA director Josef Aschbacher said in August that he had opened discussions with SpaceX officials, not necessarily for Euclid, but to relieve the European flight schedule, which had become untenable.

The affair will not be settled in a few weeks, but it is also a way of warning the member countries a few months before the large and very important ministerial assembly of the European Space Agency. The latter takes place every three years, and representatives as ministers of the member nations of the ESA will decide on its budgets as well as its future. The appointment will be scrutinized for all future missions, currently threatened by inflation which blocks budgets sometimes fixed a decade in advance. And above all, the pitcher crisis will play a central role.

11