Contents

A revolution began in the world of research around 400 years ago: microscopy developed and opened doors to unknown worlds. Right in the middle: a Brit, a Dutchman and the Royal Society, the British scientific society.

Never take anyone’s word for granted: “Nullius in verbam” – the motto of the twelve men who founded the Royal Society in London in November 1660 – they want a modern science based on experiment and fact. Today, the British Royal Society is one of the most renowned academies of science.

From then on, the twelve men – all seasoned researchers – met every week. They hire 27-year-old Robert Hooke as a curator who is to organize experiments for them. He of all people will make history.

“The then King Charles II commissioned the astronomer and co-founder Christopher Wren to devote himself to microscopy and to report what this new technology can do,” said Keith Moore, Archivist of the Royal Society. The field of research was just emerging at the time, Galileo Galilei had built the first microscopes 40 years earlier.

But Christopher Wren decides he has more important things to do and gives the job to Hooke.

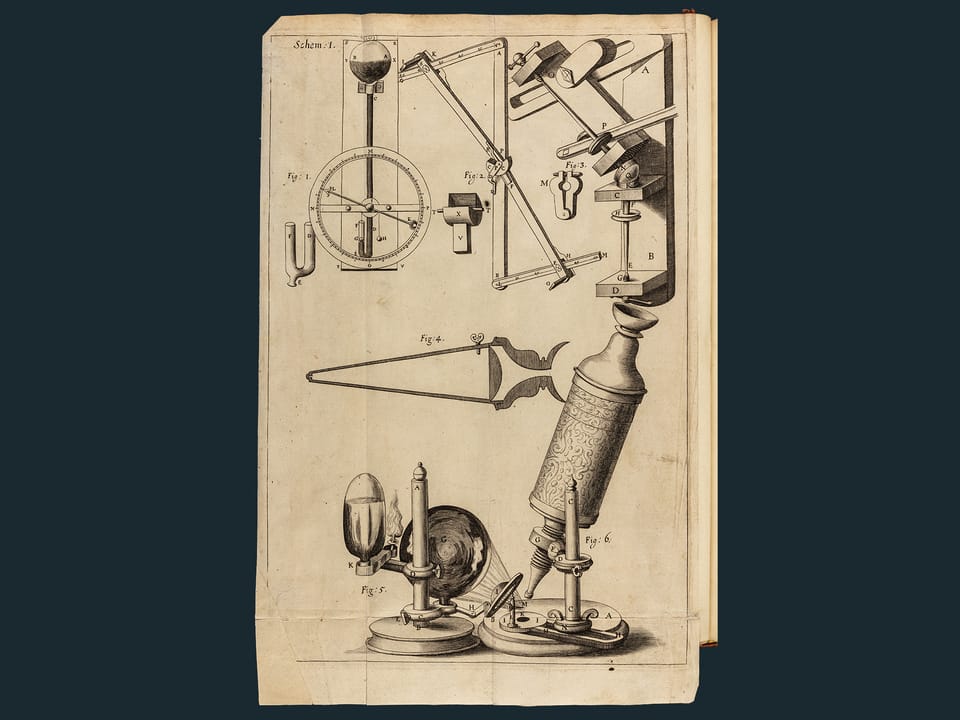

He throws himself into work. He designs his own light microscopes (see image slider), creates beautiful drawings while looking through the microscope and writes down exactly how he proceeds. It soon becomes clear that he will make a book out of it. It appears, published by the Royal Society, in 1665 under the name «Micrographia».

The Royal Society, Robert Hooke & Antoni van Leeuwenheok

The book hits. “It’s one of the first popular science books,” says Keith Moore, “almost everyone who had access to books at the time either had a copy or at least knew the book.”

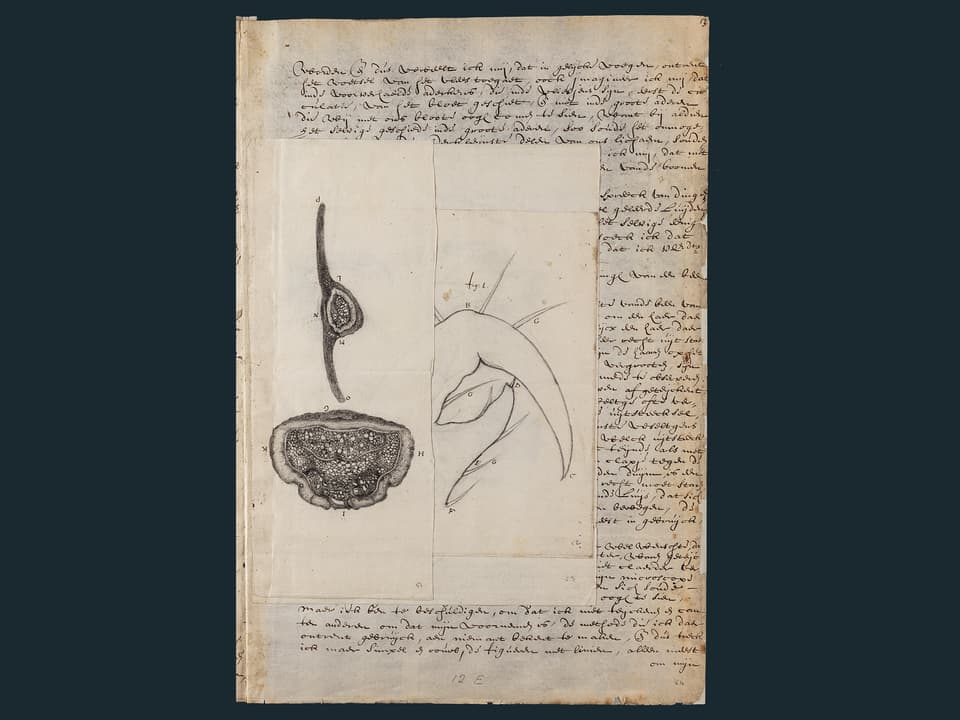

In it, Hooke shows the view of a razor blade, which no longer looks shiny and sharp under the microscope lens, but full of nicks and imperfections. He shows what grass seed looks like under the microscope. He shows the details of mold, an ant, the eye of a fly.

What makes the book and pictures so powerful: For the first time, the contrast between man-made objects, which are far from perfect, and nature, which is beautiful no matter where you look, becomes clear. “You can only understand the magic of “Micrographia” if you take this contrast seriously,” says Louisiane Ferlier, responsible for the digitization of archive materials at the Royal Society.

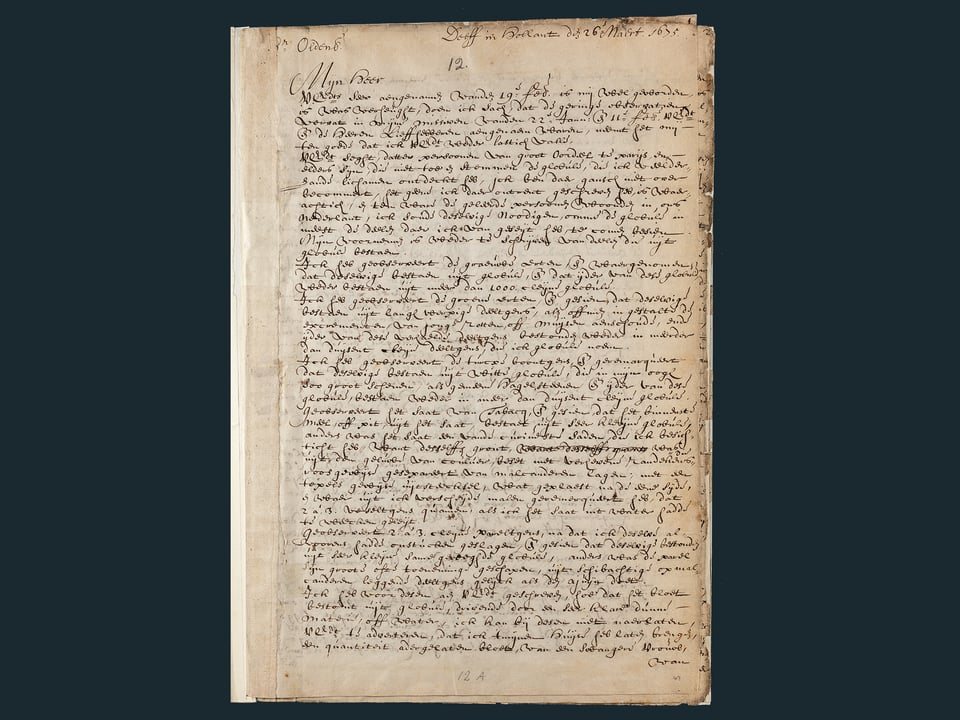

A few years after publication, a draper in the Netherlands reads «Micrographia». He too is fascinated.

First he imitates Hooke, then he builds his own microscopes. And they are completely different. “They have a small metal plate and embedded in it is a single, very small lens. There’s also a metal tip that you put on what you want to look at,” says Keith Moore. Leeuwenhoek can enlarge it up to 250 times, almost ten times that of Hooke. The Dutchman is the first to see protozoa and bacteria and the first to describe red blood cells and sperm.

“It was a wonderful time to be a researcher,” says archivist Keith Moore. “Everything Hooke and Leeuwenhoek looked at was new.”

Today, the two men are considered the founders of microscopy, without which we would not have much biological knowledge and medical treatments today. The Royal Society has lived up to its motto.