A bike in Louisville, the world heavyweight championship, a fight against the most powerful government in the world, many women, a serious illness – and yet a lot of luck. The life of Muhammad Ali is drama, thriller and fairy tale at the same time. Today he would have been 80 years old.

Joe Frazier knew the ghetto. In the rough streets of Philadelphia, the man who would become Muhammad Ali’s great rival for the boxing title at all levels learned life and survival. Eat or be eaten was the law of the ghetto. And Frazier understood.

“What the hell does he know about the ghetto?” the heavyweight champion blurted out in early 1971 when he heard what his challenger for the world championship crown announced. “I’m fighting for the little black man in the ghetto,” Muhammad Ali trumpeted in his inimitable way before the “Fight of the Century” in New York’s Madison Square Garden, thereby indirectly declaring Frazier the favorite of white America. An America that in those days wanted nothing more than a spanking for Ali.

Frazier had every reason to be angry. Indeed, Muhammad Ali did not come from the ghetto. The story of the “greatest” begins in Louisville in the US state of Kentucky. Ali, born in 1942, baptized as Cassius Marcellus Clay jr., grew up here in sheltered circumstances. The father is a sign painter and brings home a regular income. On Sundays he goes to church, during the week Cassius goes to high school. It’s almost like a “black middle class” to which the Clays belong. In any case, the Philadelphia ghetto, in which Joe Frazier had to struggle through at about the same time, is far away for the young Cassius.

Olympic mayor, world champion, conscientious objector

At the age of twelve, the teenager is the proud owner of a bicycle and furious as hell when someone steals his bike. He vows to give the crook a good beating if he ever gets his hands on him. Joe Martin, a Louisville police officer and boxing gym manager, listens patiently to young Clay’s tirades and advises the angry boy to learn to fight with his fists first. The next day, the robbed man is in Martin’s boxing hall.

While the slender Cassius unfolds his unique boxing talent in the boxing ring, his big mouth matures away from the rope square, despite (or because of) everyone in Louisville loves him. “He had a lot from my father, who was an entertainer in our family and made everyone laugh,” Ali’s brother Rahman later localizes the roots of the “Louisville Lip”. The great-grandfather’s Irish genes, revealed by Ali in 1972 during his visit to the island infatuated with boxing, poetry and Limericks, probably do the rest.

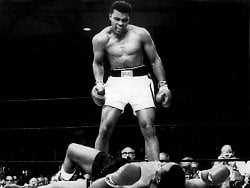

At just 18 years old, still a stranger to the razor blade, Cassius Clay is already so good that the USA sends him to the Olympic Games in Rome. In the “Eternal City”, the light heavyweight gold medal fighter not only snatches his ticket into the pantheon of boxing greats, which he will later stamp with his fights against Sonny Liston, Joe Frazier and George Foreman. He casts a spell over everyone – athletes and journalists – with his charm and becomes the “unofficial mayor of the Olympic Village” (according to the US magazine “Newsweek”).

“No problem with the Viet Cong”

After turning professional, Clay remains largely untouchable in the ring, but his blatant pre-fight shows aren’t well received by everyone. A young black man who declares himself the most beautiful and greatest boxer of all time, the “Greatest of All Time”, is too much for the bigoted America of the 1960s, in which blacks are only allowed to sit in the back of the bus. But Clay doesn’t want to be the brave champion à la Joe Louis: after winning the 1964 World Cup crown against Liston, he discards his “slave name”, converts to Islam – and as Muhammad Ali no longer makes any compromises when it comes to his beliefs.

In 1967, Ali finally quarreled with the ruling class: number 12-47-42-127 on the draft list of the US armed forces refused to order the war in Vietnam. “I ain’t got no watercolor with them Viet Cong” (I have no problem with the Viet Cong), thundered the champ to the US public. Uncle Sam doesn’t take that and hits back hard: five years in prison, $10,000 fine, revocation of his boxing license, loss of the world title. Millions of dollars and the sporting best years go through Ali’s rags. But because the then 25-year-old didn’t give in to the most powerful government in the world, because he went all the way to the Supreme Court – which overturned his conviction in 1971 – black America celebrates him as an indomitable hero. Thus Ali becomes the “representative” of the black man – and of the ghetto.

Nine kids, four wives, too many fights

Despite all the setbacks and injustices, Ali never lost his charm and appeal in the political turmoil of those years. In 1964, he needed five minutes to propose to model Sonji Roi. The marriage is almost as short-lived because Sonji is everything but the demure Muslim wife who sets Ali as the standard. He found such a woman and married Belinda Boyd in 1967. But “the greatest” usually only remains true to himself. “Ali was a real womanizer,” says Lloyd Wells, who has been an integral part of Ali’s entourage for years, once about the escapades of the champ.

Nine children (two of them illegitimate), four wives, three divorces are in Ali’s “marriage record”. Only the fourth covenant with Yolanda Williams lasts until death parts them. Meanwhile, Ali fights far too many exhausting battles in the ring. His triumph in “Rumble in the Jungle” over Foreman (1974), who was considered unbeatable, and his victory in the brutal attrition battle “Thrilla in Manila” against arch-rival Frazier (1975) make him immortal in sport. However, like so many boxing icons before him, Ali misses the right moment to retire, only stepping down after humiliating losses to Larry Holmes (1980) and Trevor Berbick (1981).

The shock came three years after the end of his career: Doctors diagnosed Ali with Parkinson’s syndrome. The disease transforms the once so nimble being into a slow, trembling, mumbling man – who nevertheless never bows to his fate. “Boxing was just the dressing room,” Ali whispers, stepping out and making the world his arena once more. It’s Ali’s second phase of life, the one outside the ring, that makes him the “Greatest of All Time”. Like no other, Ali uses the millions he hard-won in the rope square, but probably the most famous face on the planet, to make the world a little better.

“The only true religion is that of the heart”

Despite his physical ailments, he tirelessly jets around the world, campaigns for the weak and fights against racism, hunger and poverty. Ali is no longer just the “representative of the black man in the ghetto”. In 2002, the United Nations appointed him “Ambassador of Peace”. And the walking myth affects them all: the pope, various presidents, Fidel Castro. During the 1991 Gulf War, the then 48-year-old even traveled to Iraq and persuaded the despot Saddam Hussein to release 15 American hostages.

“The only true religion is that of the heart,” Ali confided to his daughter Hana in his final years. On June 3, 2016, half an hour after all vital organs had already stopped working, Muhammad Ali’s helping and unyielding heart stopped beating at the age of 74. But the spirit of the “greatest” has remained.

(The text originally appeared in a slightly modified form in the July/August issue of the specialist magazine BOXSPORT in July 2016.)