25 years ago, Germany launched its first military operation since the Second World War. NATO’s intervention in the Kosovo war was intended to prevent a humanitarian catastrophe. But it is controversial for reasons of international law. Its consequences can still be felt today.

“This evening, NATO began airstrikes against military targets in Yugoslavia. The alliance aims to prevent further serious and systematic violations of human rights and prevent a humanitarian catastrophe in Kosovo.” On March 24, 1999, Chancellor Gerhard Schröder addressed the German population in a televised address. He reports on the start of the NATO mission in the Kosovo war, in which Germany is also involved. It will last 78 days.

It has been 25 years since the first German participation in the war since the Second World War. The attacks of September 11, 2001, the subsequent wars in Afghanistan and Iraq – this one without German participation – pushed the Kosovo war into the background. Nevertheless: “The war has great significance for Germany,” says Marie-Janine Calic, professor of Eastern and Southeast European history at the Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, in an interview with ntv.de. “For the first time, Germany took part in an operation outside of the NATO alliance area and sent soldiers into combat operations. This was an immensely big step for the Federal Republic and I would say it was the real turning point in which war was no longer a means of politics was no longer an absolute taboo.”

The NATO operation in Kosovo was the escalation of a conflict over independence that had been simmering for decades and had escalated into a war in the 1990s. “There have been violent riots in Kosovo since 1996/97 that have escalated,” says expert Calic. The Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), founded in the mid-1990s, carried out raids and attacks on Serbian facilities in the area. “Serbia took action against this with special police and military,” explains Calic. “It escalated into war, there were mass crimes and expulsions.”

International negotiations failed – the Treaty of Rambouillet drawn up by NATO was not signed by Serbia. “NATO then argued that it had to end this conflict by military means in order to prevent a humanitarian catastrophe.” The alliance wanted to “prevent a ‘second Bosnia’,” says Calic, referring to the more than three-year war in Bosnia-Herzegovina and the Srebrenica massacre, which the UN courts have classified as genocide.

Shift towards humanitarian intervention

But NATO did not have a mandate from the UN Security Council, as it had in Bosnia a few years earlier, and there was no case for an alliance. “Most international law experts say that such a military operation would have required a clear mandate from the UN Security Council. This did not exist because Russia, as Serbia’s protecting power, would have vetoed it,” says Calic. The Security Council had already September 1998 demanded Serbian withdrawal. “A war effort was not legitimized by this resolution. Nevertheless, NATO later invoked it,” explains Calic. Ultimately, the attack was a political decision: “In the best case, international law was stretched, if not violated.”

There had been discussions about humanitarian intervention to protect human rights for a long time, but it was only after the Kosovo war that the so-called Responsibility to protect (responsibility to protect) anchored in international law. “The Kosovo war has put the debate about humanitarian interventions on a new footing,” says Calic. “Since then, it appears legitimate under certain circumstances to use military force to protect humanitarian rights.” Here too, the condition is that the Security Council issues a mandate. Only individual states such as Great Britain consider intervention to be permissible even without a UN mandate if the Security Council is blocked due to different interests.

However, German participation in the Kosovo war is criticized not only because there was a lack of a clear legal basis, but also because of the way it was presented by the federal government. Defense Minister Rudolf Scharping from the SPD spoke of concentration camps, mass executions and gave a drastic description of ethnic cleansing by the Serbs. Atrocities such as the Račak massacre in January 1999 and the Rogovo incident, each of which killed dozens of Kosovar Albanians – the circumstances of which have not yet been fully clarified – were also used as justification for entering the war.

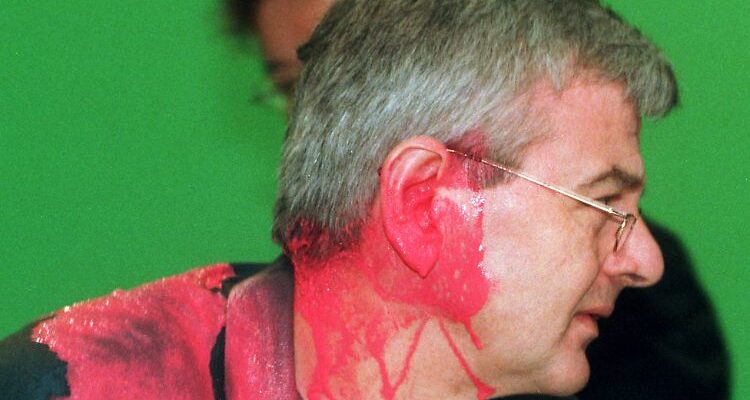

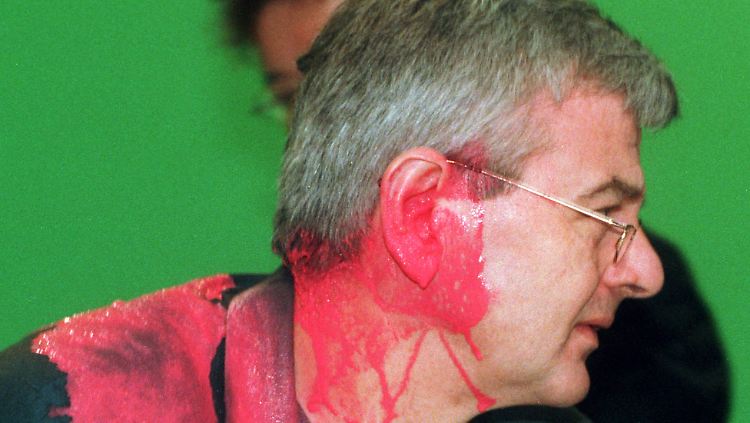

Foreign Minister and Vice Chancellor Fischer was hit by a bag of paint at the special Green party conference.

(Photo: dpa)

“Never again Auschwitz, never again genocide,” said then Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer in order to get his Green Party’s approval of Germany’s participation in the war – but by then the NATO mission had already begun. At the heated special party conference, a paint bag injured his ear, but in the end he won the majority. However, his Auschwitz comparison was met with criticism.

Scharping received sharp criticism when he put forward a horseshoe plan by the Serbian government, which was said to have involved the systematic expulsion of Kosovo Albanians, but whose existence has not yet been proven. There were also doubts about the minister’s other statements. “I don’t know now whether this oft-quoted horseshoe plan existed,” said Austrian diplomat Wolfgang Petritsch 2019 to Deutschlandfunk. He was the EU Special Representative for Kosovo in 1999. “But if you look at it in retrospect, how methodical and systematic [Serbien] what happened there, then you have to say: There was certainly planning, and that’s the nature of the military.”

Military and civilian targets

Hundreds of thousands of Kosovo Albanians were driven out by the Serbs.

(Photo: Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo)

There is no question that the Serbian troops in Kosovo were brutal, there were war atrocities and the displacement of hundreds of thousands of people. But was there a threat of genocide, as suggested by the federal government? “I am cautious about the term genocide,” says expert Calic. “If you use the United Nations definition, I would not speak of genocide. Because the Serbs were not interested in killing all Kosovo Albanians or destroying them as a group, but rather they should either leave Kosovo or leave Serbian rule accept.” She doesn’t think broader definitions of genocide make sense, “because the terminology becomes very blurry if any form of mass violence is subsumed under it.”

It cannot be said whether war crimes and expulsions would have increased without NATO intervention, because on the evening of March 24, 1999, the bombing of military and later also civilian Serbian targets by US and British bombers began. The Bundeswehr contributed Tornado Recce for aerial reconnaissance and Tornado ECR for anti-aircraft defense. Command centers, air defense positions, but also chemical plants – which resulted in massive leaks of toxic substances -, power plants – which caused the power supply to fail in parts of the country -, the Serbian Radio building – where 16 civilians died – and the Interior Ministry were attacked.

An attack on May 7 hit the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, causing major political damage. NATO said it was an oversight. Civilians repeatedly died in air raids, for example when the bridge near Varvarin was destroyed. The use of cluster bombs and the use of uranium ammunition were also sharply criticized. There was an outcry when a NATO spokesman described the dead civilians as “collateral damage” – the term became the bad word of the year. Estimates of the casualties vary widely: Serbia claimed there were 2,000 to 3,000 civilian casualties, Human Rights Watch said there were a maximum of 528. The number of Kosovar Albanians killed in the war is similarly unclear; the UN estimates there were 10,000 victims.

The war lasted longer than NATO had probably assumed because Serbia did not give in at all, not even after the massive expansion of air strikes, which also met with increasing criticism in the West due to NATO’s military errors and civilian casualties. But there were also negotiations: on June 3, 1999, Yugoslav President Slobodan Milošević, the strong man in Serbia, was finally ready to fulfill NATO’s requirements, and from June 10 the Yugoslav troops withdrew from Kosovo – with them Hundreds of thousands of people fled for fear of revenge. Resolution 1244 On the same day, the UN Security Council regulated the temporary takeover of administration by the UN and the stationing of the KFOR troops – which today still have more than 4,000 soldiers from Germany include.

An unsatisfactory compromise

Russia, which had sharply criticized the war as Serbia’s protecting power, played “a not entirely unconstructive role,” as Calic puts it. “Russia’s role should not be underestimated because it exerted pressure to get Belgrade to agree to the compromise.” At that time there was still a certain amount of cooperation between the USA, European states and Russia in the pacification of the Balkans. “This only stopped when Kosovo declared itself unilaterally independent in 2008,” said Calic. Russia interpreted this as a breach of international law – the International Court of Justice saw it differently. Russian leader Vladimir Putin used the Kosovo war to draw parallels to the annexation of Crimea in 2014.

Overall, Calic calls the compromise reached at the time pragmatic but unsatisfactory because it promised all sides what they wanted: self-government for Kosovo with the goal of independence and at the same time preserving the territorial integrity of Yugoslavia and Serbia. “This contradictory outcome of the war is also responsible for the fact that the Kosovo conflict continues to smolder to this day.”

Accordingly, the war is still present in Serbia, and not just because of the destruction that can still be seen today. “Many people experienced the war themselves, for many it was a traumatic experience,” explains Calic. Many people found the attacks on civilian infrastructure to be unfair. In addition, the NATO mission is being exploited for propaganda purposes by nationalist circles: “They are mobilizing against the West and arguing that Kosovo belongs to Serbia in terms of international law and history.”

There is still great skepticism towards the West today: “The Americans in particular, and to some extent the Europeans too, are seen as biased and one-sided,” says Calic. “Nevertheless, Serbia and Kosovo have clearly decided that they want to become members of the EU.” However, to date, five EU member states have not recognized Kosovo’s independence – because, like Spain, they themselves are concerned with aspirations for autonomy. The EU is also demanding normalization of relations from both sides, but this does not necessarily mean Serbia recognizing Kosovo under international law. In any case, Calic doesn’t think the EU is ready to accept new states at the moment: “It’s actually pretty clear that the EU would have to reform itself first.”