In order to save energy, Beijing stops the production and export of magnesium. After the chip shortage, the next crisis is looming. Industry associations warn: At the end of the year, there was a risk of production downtimes and closings of car plants. It seems to turn out differently, but the stress remains.

A few weeks ago alarm mood: after the chip bomb, the magnesium bomb is set to burst in November, warned a dozen European business associations in a joint statement. After semiconductors from China are already missing, in September the world’s largest supplier also cuts the supply of the mineral, which is important for global aluminum production – due to energy shortages and in order to achieve its own climate targets. “The current magnesium reserves in Germany, or in the whole of Europe, could be exhausted by the end of November 2021 at the latest,” the German metal trade association spreads apocalyptic sentiment.

The supply bottleneck threatened “massive production losses”. In the worst case, car manufacturers would have to close plants this year. Talks are urgently needed, so the appeal to politicians. Is Beijing turning the tap on the world for chips in magnesium and is it having to shut down Europe’s industry because there is a lack of supplies from China, as the associations fear?

It seems to be different. Beijing had actually ordered by decree that the factories – depending on age and standard – either be shut down completely by the end of the year or produce on a low flame in order to save electricity. Shortly before the warehouses in Europe run empty, however, China suddenly switches the lights on again in its factories. “Faced with ongoing concerns about a global supply shortage, the plants are ramping up production,” the writes English language portal Caixin, which belongs to a media group based in Beijing.

Gate closing panic false alarm?

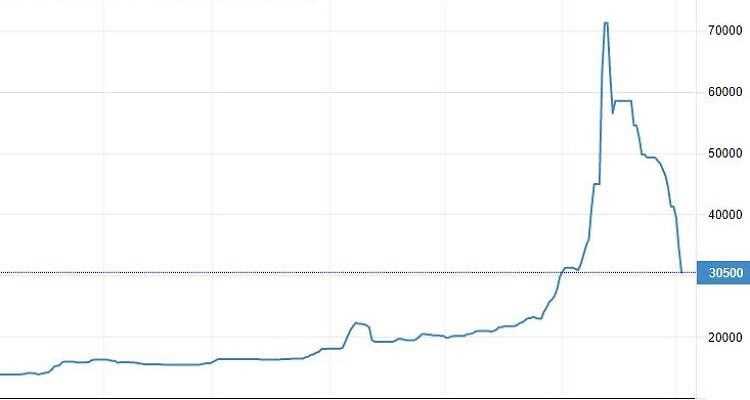

The situation is easing – although energy is still scarce in China and CO2 emissions are too high. “The magnesium smelters in Fugu have regained about half of their lost capacity since the beginning of the month,” writes the portal. According to Trading Economics the factories in the entire Shaanxi province are already running at 70 to 80 percent capacity again. At the same time, magnesium prices in the country’s most important production region are falling by almost 40 percent from their record high on September 23. And the price keeps falling. At the height of the mineral’s shortage, observers expected the price to quadruple by the end of the year.

The dwindling fear of supply bottlenecks is also depressing that Price for aluminum. Magnesium is an integral part of the entire aluminum value chain. The futures contract on the Shanghai Stock Exchange fell a good seven percent on Friday to a four-and-a-half-month low of 18,485 yuan (2888 dollars) per ton. At the LME, the metal used in automobile and aircraft construction has lost 1.5 percent and, at 2517 dollars per ton, is as cheap as it was two and a half months ago.

How precarious the situation is – or was -, whether the all-clear is now, observers are apparently divided. The fact is: China has a monopoly on important raw materials such as magnesium. Europe imports 95 percent of the minerals it needs from the People’s Republic. Other regions are no less dependent on drip: buyers in North America, Japan and South Korea have already become nervous. Even without the feared magnesium crunch, industry around the world suffers from the shortage economy emanating from China.

In Germany alone, tens of thousands of unfinished cars are waiting in parking lots for missing chips to be completed and delivered. Customer demand cannot be met even without a magnesium or aluminum crunch. Another crisis on a similar scale as the chip crisis would be almost unbearable.

Not only the auto industry is dependent on China. Magnesium is used for alloys in car bodies, cast parts and transmissions as well as in the outer skins of aircraft. The construction and packaging industry, mechanical engineering and steel production also need the mineral in production.

“Scrap is getting more exciting again”

Car expert Ferdinand Dudenhöffer does not share the concerns of the associations. The panic is “exaggerated”, he tells ntv.de. A shortage could lead to bottlenecks in the short term, but in the medium and long term it could be handled without any problems. The public “is currently hypersensitive to reporting on bottlenecks,” and emotions are “overflowing”.

In contrast to semiconductors, for example, magnesium alloys are 100 percent recyclable, according to the industry expert. Scrap from the casting of magnesium could be completely returned to the material cycle. While the production of semiconductors needs new factory capacities, the mineral can easily be drawn from the available resources: “Scrap is becoming more exciting again,” says Dudenhöffer.

Recycling not only fits in with the desire to become independent from China in the future – a goal that is not only applicable to magnesium – it also fits in with the EU’s plan to increase the recycling rate for minerals such as cobalt and lithium by regulation. The auto expert even sees another opportunity in the – possibly averted – crisis for non-Chinese industry: If there is a lack of raw material in the production of combustion cars, the desired turn to e-mobility, where less magnesium is required, will be accelerated. A positive side effect, as Dudenhöffer says. Recycling will do the rest. “It’s a lot easier than building new factories.”

“Beijing does not want diversification away from China”

“The EU is looking for alternatives to overcome such a crisis. Recycling is an important goal, it is environmentally friendly and one can reduce dependence on other countries,” agrees Gregor Sebastian from the Mercator Institute for China Studies (Merics) in Berlin. However, this is exactly what China has absolutely no interest in: “China was aware that the state of scarcity was not sustainable. They did not want to lose too much.”

From the Mercis expert’s point of view, the leadership in Beijing is prepared to accept certain economic damage. The question that the government must always ask itself, however, is: “How big can it be?” Says Sebastian. The latest GDP figures were below 5 percent. “That’s a pain threshold that you didn’t really want to end up below. Now it happened anyway.” The country earns well from the supply chains, “it’s not just about magnesium. China is well positioned for the entire range, so it wants to maintain the status quo.”

What the government absolutely does not want is to create a bottleneck that could develop into a crisis. Rather, they are interested in presenting themselves as a reliable supplier and getting out of the crisis quickly. “Ultimately, Beijing does not want the alarm bells to sound in Europe and governments make more efforts to diversify away from China.”

The fearful scenario that China rattles its sabers wants to demonstrate its power by paralyzing the Western economy is “definitely” unsustainable, Sebastian adds. The production or delivery stop is clearly related to the energy crisis in China. At the end of last year, Beijing completely stopped coal imports from Australia. Coal has become expensive. What is left is not enough to drive production forward in the way the government would like. The pressure is high. On the one hand, Beijing has to cope with the energy crisis in the country, but on the other hand it must also try to avoid economic damage or damage to its image.

How to make China self-sufficient? “We’re not drilling for oil either”

The question is how. “You can adjust the environmental problems, but not the coal shortage, you can’t change it so quickly,” says Sebastian. For the near future, it is now important to observe the situation, says the auto expert Dudenhöffer. He expects further rounds of regulation from China’s Prime Minister Xi Jinping. So it shouldn’t be exaggerated: “Should we therefore make ourselves self-sufficient from China? We’re not starting to drill for oil in Germany either because oil and gasoline are becoming more expensive,” says Dudenhöffer.

In his opinion, however, the years between 2023 and 2027 could be really problematic if a lot of lithium-ion batteries are needed. The plans for new lithium-ion productions and for the mining of important minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel or manganese are “in the making”, but the implementation sometimes takes more time to get complete value chains up and running smoothly. Bottlenecks in the development of the new lithium-ion supplier industry could delay the speed of the switch to electric cars, according to Dudenhöffer. That would be much more regrettable than short-term bottlenecks in magnesium or other raw materials.