An attack with nuclear weapons would bring Russia little militarily on the battlefield. Threatening to do so makes perfect sense for Moscow.

Launch of an Iskander-type short-range ballistic missile. With it, Russia could bring a tactical nuclear warhead to the target. Their operational range is around 500 kilometers.

Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24 this year, President Putin has repeatedly threatened the West, directly or indirectly, with the use of tactical nuclear weapons. How likely is such a scenario? How would it look? What are tactical nuclear weapons anyway?

Russian threats – European fear

The severe setbacks suffered by the Russian army in its war of aggression in Ukraine in recent months have increased fears in Europe that Vladimir Putin might actually use nuclear weapons in an act of desperation. Putin himself has repeatedly indicated that he is ready to use any means available to achieve his war aims.

The Chechen ruler and Putin confidante Ramzan Kadyrov, who plays an important role on the Russian side with his powerful private army in Ukraine, even publicly called for the use of tactical nuclear weapons in early October. Most Western observers continue to believe that the risk of such a use of nuclear weapons is low. But at the same time, it also recognizes that the dangers of Russia’s failures are growing.

Balance of terror through strategic nuclear weapons

Better known than the tactical ones are the strategic nuclear weapons with high explosive power, which, for example, can be transported far into the enemy’s hinterland with ICBMs and can destroy entire cities there. If two wartime opponents both have the so-called second-strike capacity – that is, a sufficiently large part of their nuclear arsenal can survive an attack by the other side and then be used just as devastatingly against the attacker – this is called the balance of terror.

This prevents an attack, at least as long as neither side behaves suicidal. Military theorists use this to explain, among other things, the fact that there was never a direct military conflict between NATO and the Warsaw Pact during the Cold War.

Tactical nuclear weapons have a much more limited effect

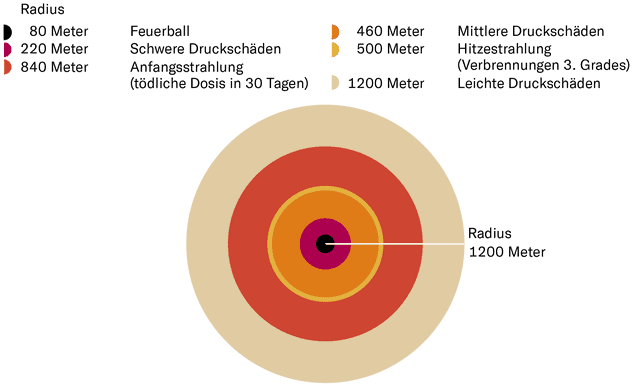

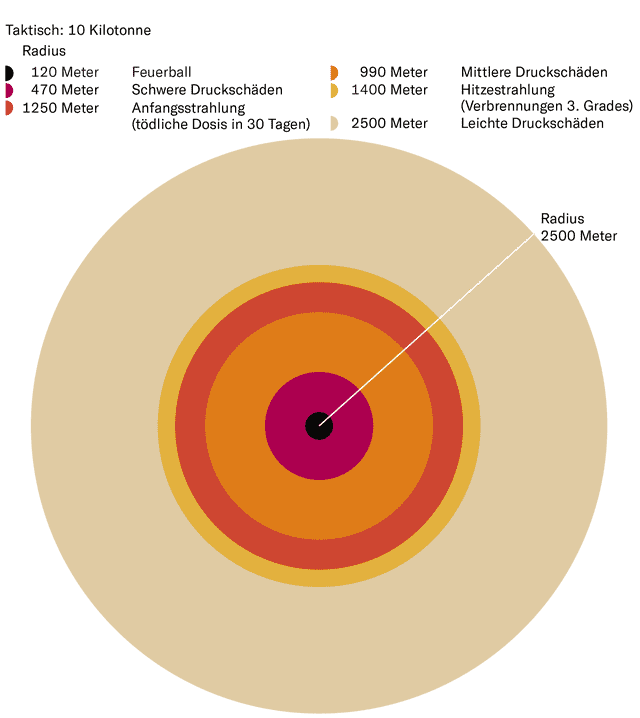

In contrast to the strategic nuclear weapons the tactical on the battlefield used to combat enemy forces. The direct destructive effect of the force of the explosion and the radiation is limited to a comparatively small area. The explosive yield of tactical nuclear weapons is generally between 1 and 50 kilotons of TNT. For comparison, the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs were 15 and 21 kilotons, respectively. Strategic nuclear weapons can have an explosive yield of hundreds to several thousand kilotons.

Here is an example: In the case of a nuclear ground detonation with an explosive force of 10 kilotons of TNT, a circular area with a radius of about one and a half kilometers would be severely irradiated and affected by moderate to severe pressure damage. A ground detonation is when the fireball hits the ground. This results in a mixing of soil material with fission products, which can rise to great heights as radioactive fallout.

In addition to the fireball and the blast wave, the so-called nuclear electromagnetic pulse, a strong electromagnetic radiation that is generated during the explosion, is also of military importance. This destroys all not specially protected electronic devices and electrical systems in a larger area.

The relatively small radius of action of tactical nuclear weapons allows them to be used relatively close to one’s own troops. Typical attack targets would be large concentrations of troops, military headquarters or wartime facilities such as airports, power plants or industrial plants. The nuclear battlefield weapons can be brought to the target with a wide variety of systems, from short-range missiles, cruise missiles or bombers to torpedoes from submarines and nuclear-tipped artillery shells.

Test in the Nevada desert

On May 25, 1953, a tactical nuclear warhead was fired from a 280 mm gun and detonated at the American test site in the Nevada desert as part of a series of nuclear weapons tests. Operation Upshot-Knothole Grable was the first test of a nuclear artillery shell. This detonated at a distance of 10 kilometers from the gun and only 159 meters above the ground with a yield of 15 kilotons. Around 3,400 soldiers took part in the exercise. The historical footage shows the firing of the cannon, the extremely bright flash of light triggered by the explosion and the formation of the mushroom cloud:

“Upshot-Knothole Grable” test of 25 May 1953 (nuclear artillery).

In addition to the force of the explosion, such a nuclear attack would also cause a large area to be directly irradiated. The damage would probably be regional. However, the radioactive fallout – radioactive dust released into the atmosphere by the explosion – could be carried farther with the wind in small amounts.

Nuclear weapons specialist Walter Rüegg, who worked for years as one of the Swiss Army’s chief physicists, considers any effects on Switzerland or Germany to be minor in view of the nuclear weapons technology used today. The Chernobyl nuclear accident released about 400 times as much of the radioactive isotope cesium-137 as the Hiroshima bomb. And today’s tactical nuclear weapons release even less radioactivity than this bomb because there is little fissile material to detonate.

Doctrine of the Russians and the Americans

During the Cold War, NATO did not rule out the first use of tactical nuclear weapons. According to the principle of “flexible response”, the Western defense alliance would have responded to a massive conventional attack by the Warsaw Pact countries with nuclear weapons if, in view of Soviet superiority, an attack could not have been repulsed in any other way.

After the end of the Cold War, however, tactical nuclear weapons largely lost their importance among the Americans. The 9,000 or so tactical nuclear warheads in American arsenals at the time have been reduced to around 230 today. They have been completely eliminated from the stocks of the army, navy and marine corps, only the air force still has a remainder. The dismantling took into account the fact that a similar effect can be achieved with modern conventional weapons on the battlefield without having to accept the radioactive contamination.

The Russians have also significantly reduced the number of their tactical nuclear weapons in the same period, from an estimated 13,000 to 22,000 to around 2,000. Exact figures are not known. According to Soviet and later Russian doctrine, tactical nuclear weapons are only used if the enemy has previously launched a nuclear attack or, in the case of a conventional attack, if the survival of the state is in question. Thus, if Putin were to order an operation under the current circumstances, he would be violating his own military doctrine. Ultimately, however, this is not binding for him as Commander-in-Chief.

How could an attack proceed?

If Vladimir Putin nevertheless decides to use tactical nuclear weapons, at least three scenarios imaginable. A first would be a warning shot, so to speak, that is, an explosion in a place where no great destruction would be caused. For example, this could be a high-altitude detonation over the Black Sea or in an area that is sparsely populated. This would serve to threaten Ukraine and NATO more seriously, without causing serious damage, and to show that Russia does not shy away from using the nuclear bomb.

A second possibility would be a strike against an important military object or significant Ukrainian infrastructure in the combat zone. However, it is questionable whether this would benefit the Russians militarily. The Ukrainian troops are widely distributed in the country, there are no large concentrations of troops that would allow the killing of large numbers of soldiers and the destruction of much military equipment. In addition, Putin would have to strike in or near a region that Moscow is now claiming as its own territory.

A third option would be an attack outside the actual war zone or even on a NATO country. In the first case, the damage is likely to be far greater than the benefit, because it would definitely make Russia a pariah. In addition, this is unlikely to change much in the military situation. An attack on a NATO country would aim to incite the population in the alliance area against the war and thus dissuade the NATO states from continuing to support Ukraine.

But this would automatically trigger the NATO alliance case under Article 5. A massive Western response would be inevitable. This would create a much stronger opponent for Moscow. What answer the NATO countries would have ready in this case is secret. By leaving Moscow in the dark, they make planning more difficult. Jake Sullivan, President Biden’s national security advisor, recently spoke of “catastrophic consequences” for Russia in this case.

This would not necessarily have to be a nuclear counterstrike. For example, eliminating the Russian Black Sea Fleet with massive conventional means would also be conceivable, as suggested by David Petraeus, the former CIA director and former supreme commander of NATO troops in Afghanistan.

For the Russians, a nuclear strike would hardly be effective

The use of tactical nuclear weapons would therefore hardly bring Putin any military advantages. As long as the ruler in the Kremlin is thinking rationally, he must come to the conclusion that the use of tactical nuclear weapons will not get him out of trouble militarily. However, if his actions are driven by sheer anger, even if the West gives in out of sheer fear, this will not prevent it from resorting to nuclear weapons in the long term.

The mere threat of a nuclear bomb, on the other hand, can very well be helpful to Putin. He can still speculate that this will mobilize the population, at least in certain NATO countries, against supporting the Ukrainians’ defensive struggle. If he actually succeeded in driving a wedge between Ukraine and the NATO states, he would have achieved his goal. Because without Western support in the form of arms deliveries, Ukraine will not be able to withstand Russian aggression for long.