Putin has now been in power for twenty-two years. During this time he has not presented a single political program or a single political idea, but only created an ideological fog that is wafting away. And has now led to the great war.

“The larger the number of people the liar has convinced,” wrote Hannah Arendt in 1964, “the smaller the chance that he himself can still distinguish between truth and lies. From this it follows that lying in public (. . .) is incomparably more dangerous than private deceit.”

In fact, the war in Ukraine only became possible because the Russian government has been consistently lying for years and because people in Russia allow themselves to be lied to. They have no inner defense against lying, because Putin’s pathetic and at the same time so seductively simply concocted worldview is more comfortable for them than reality, which is fraught with irritating contradictions.

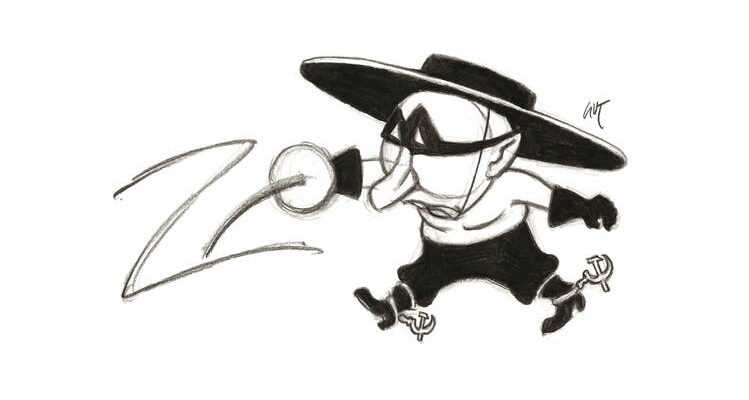

The essence of “Zigism”

Above all, this world view is supported by the Soviet past that has never been dealt with and in particular by the glorification of Stalin and his role in the Second World War. Not only does this obscure the totalitarian character of the Soviet leadership, it also creates the euphoric myth that the point is to continue the victory over Nazi Germany forever. The brazen lie about the necessary “denazification of Ukraine” would not have been possible without this mendacious historical policy and the dangerous manipulation of the “victory consciousness”.

Exiled Russian journalist Julia Latynina recently described the current regime as “Zigism”. She is alluding to the mysterious letter Z, which first appeared on Russian military equipment deployed in Ukraine and then became an important propaganda symbol in Russia itself.

What consolation remains for Russia’s people is pride in their own transfigured history, which never existed in this form.

It is remarkable that no one knows exactly what Z means. Kindergartens and schools used it to show their support. Organizations and companies were sent official but vague and contradictory regulations on how to use the mark. Some believe that this is a desire to win. Z would then stand for the slogan “For victory!” («Za pobedu!»). On the one hand, this is strange, because for some inexplicable reason the Cyrillic letter has been replaced by a Latin one. And on the other hand, it sounds absurd when this misspelled “Zieg Heil!” means a “goat” of which no one has any idea what exactly it is supposed to be.

“Everything is going according to plan,” the Kremlin’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, kept saying. But what is the plan of the so-called special operation? Both the occupation of Ukrainian territory and the regime change in Kyiv are denied by the Kremlin as war aims. It shouldn’t even be about a war. And yet there is an inexplicable joy among supporters of the regime at the bloody confrontation. Its futility in no way diminishes the belief that it is right.

Just as the Z symbol is highly charged but meaningless, so too does “Zigism” represent a doctrine of meaning and intellectual impotence. What’s more, both the Z and the idea of victory are in fact deeply apolitical, they have no meaning and do not affect any real concerns of the Russian people. On the contrary, they distract from them. “Zigism” stands for a system of rule in which there should be no political space.

Just don’t have to lie anymore

Many of the estimated 100,000 people who left Russia after February 24 say: I couldn’t stay because I didn’t want to lie anymore. The accent is on “no longer”: What worked for years, what was willing to ignore, mock, downplay, is now no longer acceptable. Looking back on the last two decades is painful, they now appear to be a fatal error. Many well-intentioned efforts and initiatives ultimately remained fruitless, many newly established businesses failed.

Above all, for people who are now going into exile, the existential formula “I move beyond politics” (“ja vne politiki”) is proving to be no longer tenable. Putin’s regime benefited from the bubbling revenue from the gas and oil trade, but also from the many people who preferred not to know what the top government was up to. Whatever happened “up there”, the population knew that it was better not to care.

It is an ideal situation to start a war. The word does not appear in the media, and the Ukrainian army does not exist either. Instead, there is talk of “fighters”, “national battalions”, “nationalists” or “neo-Nazis” who – for many weeks! − fight in Ukraine against the Russian army against their «liberation». It never occurs to anyone to ask what role the regular units of the Ukrainian army play.

Meanwhile, there is a threat of high penalties for anti-war protests in Russia. The poster «No to war» represents a defamation of the army, a photo posted on social media of the bombed Mariupol extremism, the slogan «Vote against Putin» hooliganism. It is better to save yourself the trouble of arranging the whole thing logically. In general, Russian sociologists report that it is currently much more about belief than thinking. The numerous conflicts in families and among friends are sparked off by the question of what one “believes”.

Even those who need to know that the realities in Ukraine are not those of television do not want to penetrate to the knowledge. Just as many in Russia still do not want to believe in the extent of state terror and mass extermination under Stalin, they consider the crimes of the Russian army in the two Chechen wars to be impossible, do not want to see that Russia started a hybrid war in Donbass in 2014, point out back that Alexei Navalny was poisoned and refuse to accept that the Russian army is trying to destroy Ukrainian cities and their population.

Ignoring reality is one of the most important maxims in the political culture of today’s Russia. Only two types of loyalty are allowed: loud and sincere support, and silent and hypocritical support, loyalty “as if”. For many years it was possible for the urban middle and upper classes to live apolitically under Putin and share in the blessings of prosperity. The regime used only as much lies and repressive violence as necessary to keep the population from political engagement – no more.

This created a buffer zone between the population and the state elite or state bureaucracy, a taboo area. “Let’s not talk about politics” or “I don’t want anything to do with politics”, this attitude became a basic attitude. And not just in Russia, Western actors too were willing to let Putin lather them up at the price of complicit or indifferent silence.

“So the danger of propaganda, if it conceals or denies facts, lies not only in the ruin of free opinion-forming, but also in the perversion of real political conflicts, which have their roots in fact,” Hannah Arendt aptly notes. In Russia, the term politics is equated with state power and Putin, “being political” means being critical of the ruling regime. There is not much left of the political.

The arbitrariness of the corrupt state leadership is borne by the arbitrariness of their language. Concepts are cynically twisted and profaned, the language starves and thirsts. Whatever happens, the leadership around Putin will call it whatever suits them. And what can be said against a language that is so random that semantic and logical norms no longer apply?

False consolation

Subversion and manipulation have been the means by which KGB man Putin has ruled the country from the start. Putin has succeeded perfectly in the “domestic political experiment of transforming fact into fiction,” to use Arendt’s apt expression. He has now been in power for twenty-two years, and during this time he has not been able to present a single political program, not a single political idea, not a single vision, not even a real ideology, just ideological fog that is wafting away.

His regime differs from the totalitarian Soviet Union under Stalin in three respects: 1) The borders remain open so that all “traitors” and “internal enemies” can leave the country and mass arrests and mass shootings can be avoided. 2) There is no leading party, no broad political movement holding power. 3) And consequently also no utopia that can mobilize the population for a better future.

For Putin and his cronies, this is the definitive lesson from the collapse of the Soviet Union. The authoritarian state can also perish if the population mobilizes. Authoritarian power is far better off without a political vision. With the reference to a dystopian, “broken” world view in which there are no longer any normative models, the citizen should be kept as far away from the political space as possible.

Power cannot be cemented with hope and utopia, but with disappointment and nostalgia. It is a new breed of nihilistic authoritarianism that thrives on futility and absurdity rather than a promise of a better future. What remains for Russia’s people as “consolation” is pride in their own transfigured history, which never existed in this form.

Anna Shor-Chudnovskaya is a research associate at the Department of Psychology at the Sigmund Freud Private University in Vienna. Research interests: social change and political culture in post-Soviet Russia.