Rob Epstein and Jeffrey Friedman had made in 1995 an instructive documentary on the representation of homosexuality in Hollywood, The Hollywood Closet. Five years later, they accentuate the register and do pioneering work by evoking the fate of homosexuals during the reign of Nazi barbarism. The film was shown at the Berlin Film Festival in 2001, where it won the Golden Bear in the category, before being released, notably in France. Almost invisible since then, here it is again accessible, again demonstrating its great quality and recalling, in a context of extreme right-wing states and consciences, to what the policies of the worst lead inexorably.

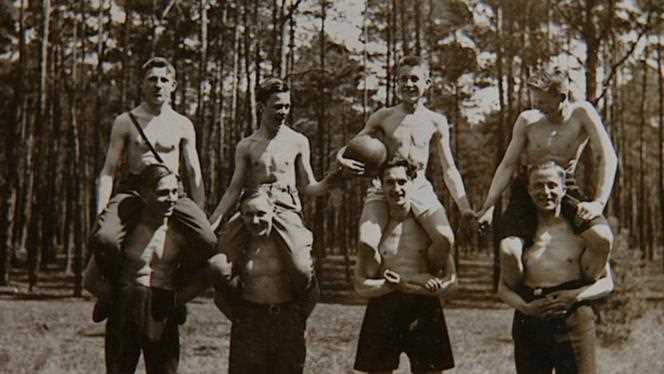

Surprisingly compact in terms of such a subject (eighty minutes), the film demonstrates, notwithstanding dazzling virtues of pedagogy and emotion. Guided by historian Klaus Müller, using both archives and unpublished testimonies of men and women persecuted during the war, he raises the question of intolerance and homophobia in Germany over the long term. Recalling that the famous paragraph 175 of the German penal code criminalizing homosexuality was drafted in 1871, that it will remain untouched until the 1970s despite a period of unbridled liberalization of mores during the Roaring Twenties, and that homosexuals were not seen never recognized as victims of the postwar Nazi regime and continued to be tried according to the letter and spirit of this law.

Ten thousand homosexuals deported

This, which is uncomfortable to say the least, pales in comparison to what constitutes the heart of the film: their persecution during the Nazi regime. Approximate figures are given here, which put things in place both from the point of view of the ignorance in which this persecution was held, and that of an activism of the cause which suddenly increased its amplitude. About a hundred thousand homosexuals, the vast majority of them male, were arrested, exclusively in the German protectorate zone, ten thousand of them were deported and six thousand murdered in the camps. Others – homosexuality then being a pathology subject to re-education – were deliberately incorporated into the army.

However, it is the words of these victims that make this film overwhelming. Long repressed in view of post-war politics and the stigma of shame, she frees herself here with dignity and sensitivity. Reported to the voices of survivors of the Jewish genocide, where the overwhelming and dereliction accompanying the killing of an entire people stamp each word uttered with their seal, we find here other nuances. A formidable sensual vitalism for example, which never forgets the business of seduction in the darkest of persecution, such as this story by Gad Beck, which tells how he put on the uniform of a member of the Hitler youth to go shoot his boyfriend Jew, Manfred, at the hands of the Gestapo. The soldier on guard tells him “Are you bringing it back to me?” “, he answers her “What would I do with a Jew?” “. But his friend will return to the school on his own initiative to join his family.

You have 19.93% of this article to read. The rest is for subscribers only.