In Switzerland, the Yenish people, a national minority and traditionally traveling population, were persecuted for decades: employees of Pro Juventute, a foundation that actually advocates for children’s rights, took over 600 children away from their parents by 1972 and placed them in farming families or children’s homes.

Many of these children never saw their families again, were abused and labeled as second-class citizens for the rest of their lives. Some professionals are now talking about genocide.

Jenische: denigrated as “degenerate, immoral, crazy”

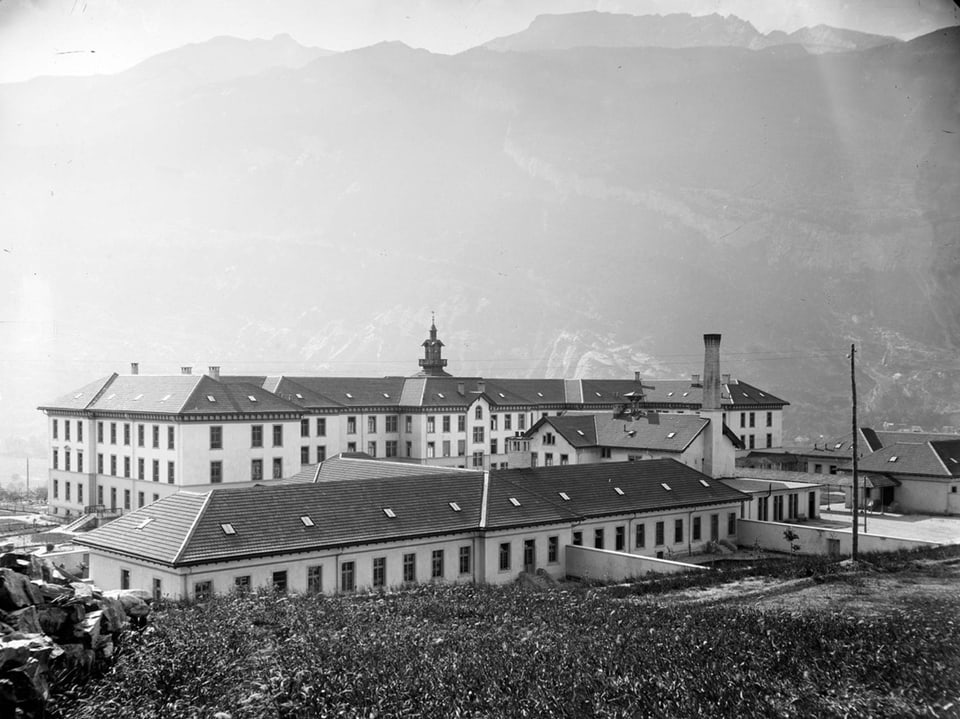

The search for the ideological basis of this persecution leads to Graubünden, to the Waldhaus Psychiatric Clinic in Chur, founded in 1892. Its first director, Johann Joseph Jörger, described the Yenische as “degenerate, rough-tempered, immoral, crazy”.

Legend:

At the Waldhaus Clinic in Chur, psychiatrists wrote stigmatizing reports about Jenische.

STAGR

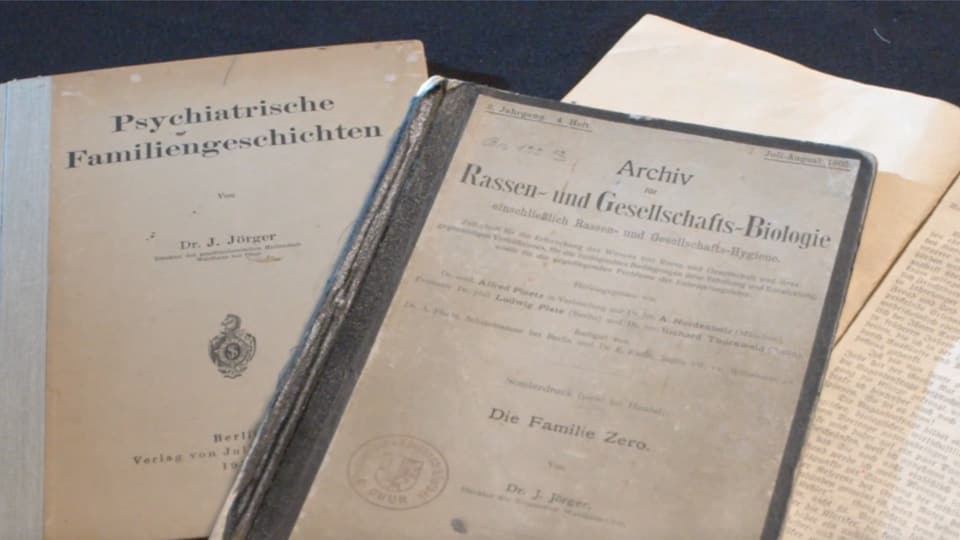

There is “no other means than the very early removal of the children from the family and the best possible upbringing and raising them to a higher social level,” wrote Jörger in his 1905 book “Psychiatric Family Stories.”

Graubünden clan studies and Berlin Nazi racial theory

Jörger’s works were published by the “Archive for Racial and Social Biology” in Berlin and were received with interest by eugenicists in Germany. Robert Ritter, the head of the “Racial Hygiene Research Center” in Berlin under Hitler, also cited Johann Joseph Jörger from Grisons, among others.

Legend:

Generations of Graubünden clinic directors defamed the Yenish people in their books.

Film still from: “Insights into Psychiatry”

The result of the pseudoscientific studies: In Germany, hundreds of thousands of Sinti, Roma and Yenish people were deemed “inferior”, subjected to horrific medical experiments and sent to die in concentration camps.

Yenish women under observation

In Switzerland, from 1926 onwards, Jörger’s works were used by the “Children of the Landstrasse” foundation, a Pro Juventute project, to legitimize the dissolution of dozens of Yenish families. Women were particularly targeted.

Legend:

Alfred Siegfried, founder of the so-called “Children of the Country Road” relief organization, tore hundreds of Yenish children away from their parents.

Film still from: “The Last Free People” 1991

“The aim was to prevent the Yenish women from introducing the itinerant way of life into the settled families and thus spoiling the entire society,” explains Hans Caprez, who documented the persecution of the Yenish people as a journalist for the “Observer”. Therefore, Yenish women were forced to be sterilized and their children were taken away from them.

Traumatic experiences in the children’s home

One of these children was Maria Zampatti, who came from a Yenish family from Graubünden – a relative of the writer Mariella Mehr. Zampatti spent her childhood in various homes and foster families.

“As a bedwetter, I wasn’t given breakfast as a punishment and had to stand in the dining room with a wet sheet, ridiculed by the other children,” recalls Zampatti in the 1991 documentary “The Last Free People” by Oliver M. Meyer.

Legend:

Maria Zampatti experienced violence and abuse in homes and foster families.

Film still from: “The Last Free People” 1991

Maria Zampatti fought back and was punished even more severely. At the age of 16, she was taken to the notorious Bellechasse prison – without trial and without judgment. She spent three years in Bellechasse – the worst experience of her life.

No break with history at the end of the war

Unlike in Germany, the end of the Second World War in Switzerland did not represent a break with the past. In Graubünden in particular, generations of psychiatrists clung to stigmatizing practices. They not only wrote defamatory pseudo-scientific works, but also prepared reports that described Yenish women and men as “violent,” “alcoholic,” or “morally weak-minded.”

Legend:

The Bellechasse prison in the canton of Fribourg. Over a hundred “children of the country road” ended up here – even though they had never committed any crimes.

Film still from: “The Last Free People” 1991

Waldhaus director Gottfried Pflugfelder insulted the Yenish people in an article in 1961 as “parasites of this society” and emphasized: “As a hereditary and sociological example, Graubünden vagrantism can claim special scientific interest.”

Anti-Yenish tradition in Graubünden until 1991

In 1972, the “Children of the Country Road” foundation ended its activities due to public pressure. A series of articles by Hans Caprez in the “Observer” was the trigger. In Graubünden, however, until 1991, the Waldhaus Clinic was headed by a man who followed in the tradition of his predecessors: Benedikt Fontana.

Legend:

Clinic director Benedikt Fontana defended the anti-Yenish “research” until his retirement in 1991.

PDGR

In his dissertation, Fontana lists the genealogies of these families. A thin booklet of 58 pages, peppered with defamatory statements like this: “Until she came of age, she was in various institutions, where her impudence and quarrelsome nature were repeatedly highlighted. In freedom she failed again and again. Finally she was examined and she was described as moronic, baseless and morally weak.”

Vain resistance

Maria Zampatti, the girl from the children’s home, was amazed when she got her hands on Fontana’s dissertation decades later. In the meantime, she lived an unremarkable life as a caretaker and mother, despite traumatizing experiences in her childhood.

Legend:

Maria Zampatti defended herself against the discriminatory reports. However, the canton of Graubünden did not respond to her request to revoke clinic director Fontana’s doctorate.

Film still from “The Last Free People” 1991

Fontana had never spoken to her personally, but had simply copied the reports of his predecessors for his doctoral thesis. That’s why Maria Zampatti demanded that the canton of Graubünden revoke the doctorate from the director of the Waldhaus Clinic. Vain.

«Dr. med. “Benedikt Fontana wrote his dissertation as a private individual and not on behalf of the canton,” the canton said. “The dissertation was accepted by the medical faculty of the University of Bern without reservations.”

Fontana remained in office until his retirement in 1991. Only then did a new era begin in Graubünden psychiatry.