The Peruvian writer and Nobel Prize winner recalls that he was late in moving away from the philosopher who justified Stalinism in the 1950s.

1954: The French novelist essayist and dramatist Albert Camus (1913 – 1960). (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

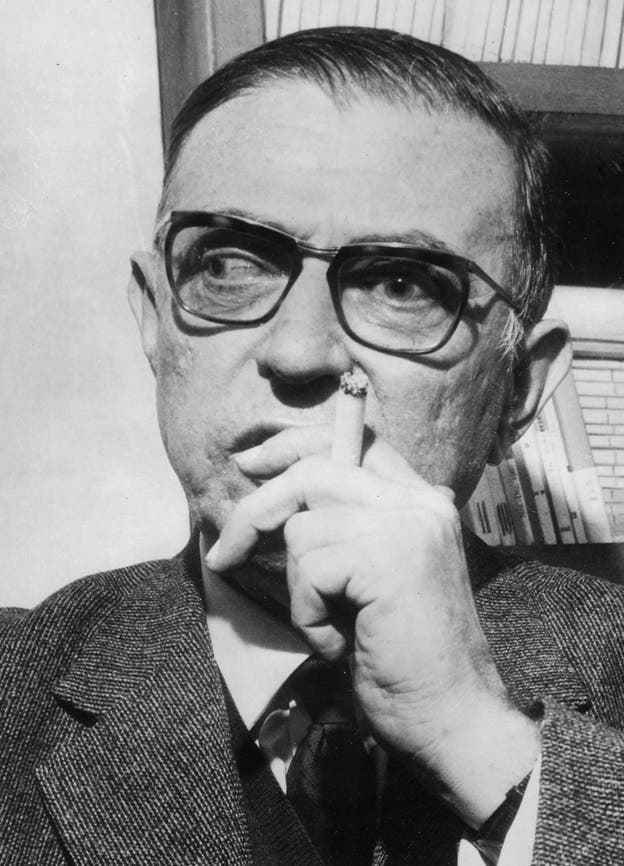

circa 1965: French writer and philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre (1905 – 1980). (Photo by Keystone/Getty Images)

Albert Camus (left) and Jean-Paul Sartre differed sharply in their assessment of Stalin’s regime of terror. In 1952 they got into a heated argument about it.

Did you think the anarchists were gone? Not even close. According to the Venezuelan sociologist Rafael Uzcátegui, they were in excellent health. In a recently published book, he criticizes Nicolás Maduro’s government and accuses him of being responsible for the mistreatment and torture of political prisoners and the murder of critics of his regime.

A member of numerous associations, Uzcátegui has refrained from planting bombs or using a weapon and champions the noblest of causes: he defends political prisoners, takes care of their protection and looks for countries that are willing to do any kind to take in refugees. His essays are unusual because the Latin American left does not usually take such a democratic stance. Moreover, he is not only a theoretician but also a man of action.

His book is entitled “La rebeldía más allá de la izquierda” (The Rebellion Beyond the Left) and advances a very attractive, but in my opinion wrong or at least daring thesis: the polemic between Sartre and Camus in Paris in 1952 was the Reason for the infantilism of the Latin American left, its inability to cooperate with other progressive forces and its hermetic dogmatism, as it is displayed in his native Venezuela by the government, which does not cooperate with anyone but the Cuban government. I am afraid, however, that the polemic between Sartre and Camus did not spread and was discussed as vigorously in Latin America as Uzcátegui claims, but went almost unnoticed.

Sartre on Stalin’s penal camps

I remember this polemic well because at the time I was an ardent supporter of Sartre and all of his positions, including the claim he was to regret: that in the USSR, which he visited with Simone de Beauvoir in 1953, all citizens right to criticize the government. He later said he lied when he wrote that.

I remember the enormous difficulty, with my teacher at the Alliance Française, the unforgettable Madame del Solar, in «Les Temps Modernes», the article by Francis Jeanson that triggered that polemic (it was full of inventions and lies about Camus), and to locate the essays by Sartre and Camus that followed him. Later, after the latter died in that stupid traffic accident at the age of 46, Sartre published a warm note declaring that Camus had been his best friend. It didn’t look like it. In truth, they fought for intellectual leadership in France at the time.

This polemic was primarily about Stalin’s unyielding anti-democratic attitude, that is, about the Soviet penal camps for – actual or supposed – dissidents. Sartre did not deny their existence, but justified them in the name of future socialism, which he believed would abolish the injustices of a government forced to resort to these camps in its own defense because of the right-wing enemies in the world. As if the blood of the innocent were a punishment for the guilty; an unbearable thesis.

Camus believed that a decent human rights person should denounce the excesses of violence against dissidents in the USSR as well as the misdeeds of right-wing dictatorships and governments. That position seemed a lot more reasonable than Sartre’s, but at the time many of us didn’t see it that way.

From then on, the supporters of Sartre and Camus – who was said to be France’s most important thinker – split into two warring factions. I confess that my admiration for Sartre led me to continue to support him and that I only broke with him a few years later when he told Madeleine Chapsal, the director of the literary section of Le Monde, that African writers should renounce literature to carry out the socialist revolution first.

He, who had taught us that one could be a writer anywhere in the world in order, among other things, to denounce the misdeeds of the reactionary forces, now like some fanatic condemned us to make the revolution instead of being writers. For me, who had already chosen literature, not least because of him, this meant the end of my admiration for the French philosopher.

At least, that’s what I thought, but deep down, the old enthusiasm for the existentialist thinker lives on, and occasionally comes out when a journalist or a book reminds me of the positive things they’ve written or done in their life. And there were quite a few.

Moscow’s henchman

But the polemic between Sartre and Camus only appeared in Les Temps Modernes and, to my knowledge, did not find the slightest response in Latin America. Anyway, I can’t remember, and during that time I was involved in many political affairs across the continent. I think the Peruvian communists were no different than any other country, although the polemics in Mexico or Argentina, which are the larger countries, may have received some attention. But definitely not a big one.

However, Rafael Uzcátegui believes the opposite, and reading his essay one gets the impression that the entire left of the new continent, having become aware of the polemic, split into those who favored a Stalinist line of systematic rejection of all other socialist currents, and those who agreed with Camus’ moderate positions. In any case, I was not aware of this great controversy, and I don’t even believe that it existed at all.

My impression is that the intolerance of the Latin American left has its roots directly in the events in Moscow and their communist party leaders were nothing but blunt tools of the Soviet government, which is why communism has always played a very minor role in almost all countries of the new continent, even in Bolivia during Paz Estenssoro’s first term.

Later there was the argument about the importance of the guerrillas, to which the communists and Moscow were quite allergic, while Fidel Castro supported them, at least by distributing millions of copies of Régis Debray’s booklet The Long March. I remember well that debate that took place all over the continent and caused so many deaths, at least in Peru.

For the rest, Rafael Uzcátegui’s book is quite likeable and convincing. It reads pleasantly and easily. I wish there were such a sane left in Latin America as he and his friends (very few, I’m afraid) describe in the pages of his book (published in Venezuela, of course), which is interspersed with caricatures between its author’s clever essays and includes a foreword by Tomás Ibáñez. But such a left does not exist, or it is not strong enough to give its extremist supporters a left-wing democratic undertone.

The intolerance of these supporters is directed primarily against the democratic left and democracy in general. It is a true Stalinist obsession, as has been shown in these months when, faced with the insanity of Vladimir Putin and his followers, almost all left-wing governments in Latin America have invaded Ukraine, arguing there that the Ukrainian government is a gang of Nazis, committed unspeakable crimes, remained silent or, worse, supported Putin.

In the fight for human dignity

I don’t think anarchism has a great future in Latin America and the world. It is an ideology that was wrong from the start, when its adherents resorted to direct action and murdered their supposed bourgeois enemies, and these crimes were rejected by the majority and condoned by only a few. It is all the more encouraging that Rafael Uzcátegui and his friends are adopting a much more open and tolerant attitude, professing a democratic will in their political actions, something their predecessors lacked. And that’s why they failed.

Politically I was never very fond of anarchism, but as a writer I was. The adventurous biographies of many of his spokesmen, particularly Bakunin, made me want to talk about them, which I certainly would have done if so much had not already been written about them.

Rafael Uzcátegui and his friends are less violent than the anarchists of their parents’ generation, but far more effective in their fight for the dignity of refugees around the world. There are millions and every refugee is different. The attitude of Uzcátegui and his friends is commendable: helping everyone without asking why or from whom they are fleeing. They all deserve our sympathy and help, despite the ideas Jean-Paul Sartre put forward in that polemic with Albert Camus.

The Nobel Prize for Literature Mario Vargas Llosa was born in Peru in 1936 and has been living in Madrid for almost three decades. © Mario Vargas Llosa, 2022. – Translated from Spanish by Carsten Regling.