Marcel Proust was only able to write his work of the century after his mother was dead. Precisely because she was involved in it. The French writer died a hundred years ago.

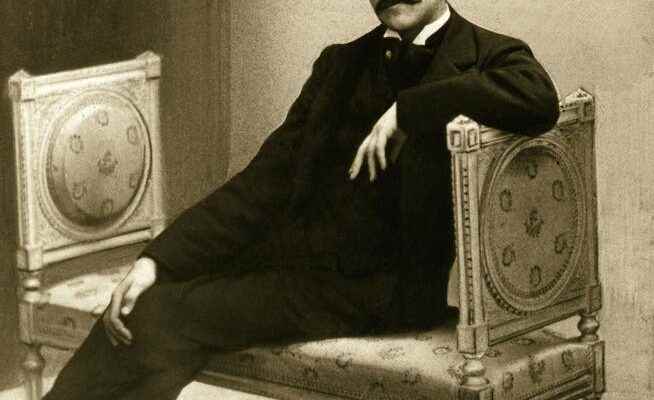

«À la recherche du temps perdu» is also one of the greatest mother novels in literature. The tragedy of a special family relationship lies in this work. Marcel Proust around 1896.

It’s a different kind of research. On October 20, 1896, Marcel Proust telephoned his mother. She is at home in Paris and he is in Fontainebleau for a cure. The homesick twenty-five-year-old hears Jeanne Proust’s slurred words on the phone. The writer will ask himself for a long time later what that was: a very close sound, but from an unreachable distance. “A small, cracked voice that was forever different from what I had known before, as if bruised, cracked and chapped.”

Proust is experiencing a new medium, the technical inadequacy of which strikes him as a cosmological crackle, but he is also experiencing himself. The telephone receiver is the prosthesis of a tenderness in which the son feels connected to the mother as never before .

Marcel Proust will return to the experience again and again in his work and in his letters, transforming it in literary terms and even ironizing it at one point. When the narrator of “À la recherche du temps perdu” tries to call a young woman who is not just a fantasy, the Mesdemoiselles from the telephone exchange have something to report: “The line is busy.”

Marcel Proust’s line is often busy. Metaphorically speaking. “In Search of Lost Time” is a grand novel of sublimation. Attempts at intimacy usually dissolve into platonic and bodily ambiguities, eroticism remains a shadow play on the tapestries of the salons. Why? The “Research” is also one of the greatest mother novels in literature. The great tragedy of a special family relationship lies in this work.

The little wolf

It has been read psychoanalytically and the novel has been viewed as an Oedipal Hydra whose many-headed figure is in fact always the body of Jeanne Proust. Even in the style, in the breathlessness of the sentences pushed into one another, it is perhaps still possible to discern in a psychopathological way what connects Proust’s mother and son: Marcel’s asthma. The illness warrants constant concern. The patient remains the protagonist of a lifelong catastrophe. Before that he must be protected using all his own resources and with uninterrupted attention.

When the mother is terminally ill, a nun employed to care for the mother says to Marcel Proust: “In her eyes, you were always four years old.” Proust was still the “petit loup”, the “little wolf” when his mother died in 1905. He is thirty-four and still lives at home on the Rue de Courcelles in Paris. The fact that the mother, who comes from a wealthy family, threw herself protectively between her child and life for more than three decades is noticeable in this grown-up child as well as in the life it leads.

When the son came home in the evening after going out, his first question was: “Is Madame there?” The troubled mother then appeared from the depths of the apartment as if she had awakened from an absence. Her fear: Marcel could be exhausted from the hustle and bustle out there. Proust’s greatest concern was having worried his mother. It was the dilemma of highly invasive and mutual concern that two people might have walked into on purpose, trying to save themselves.

Marcel Proust is said to have acted “like a clumsy lover” towards his mother, writes the biographer Ronald Hayman, and he is not the only one who has taken on this special relationship, right up to the standard work by Jean-Yves Tadié. One can dabble in psychoanalysis and still follow tracks in Marcel Proust’s oeuvre that are hermeneutically fruitful. The mother is the retarding element. It stands between the ego and the world and creates the delay from which Proust writes. Everything in Proust is delay. Wiring experiences with sensations was not a work of the minute for him, but preparatory work for a work of the century.

The years in the writing bed

Do we have to be grateful to a mother who is not neutralized by the formula “ma mère” in the intimate passages of “Research” but is instead called “maman”? Marcel Proust answered the famous questionnaire, which is now named after him, twice. When he was thirteen, when asked about the greatest misfortune imaginable, he wrote the sentence: “Being separated from Maman.” At nineteen, the answer is: “Knowing neither my mother nor my grandmother.”

Up until the death of Jeanne Proust, the maternal love machinery ran on ever more eccentric paths. In concern for the son, his social interactions are monitored as well as his wardrobe, his medication and his bodily functions. The hypochondriacs Jeanne and Marcel join forces in amateur self-diagnosis against their father Adrien, who is a doctor.

It is a drama similar to that of Gustave Flaubert, whose father is also a doctor. It is no coincidence that the hypochondriacs Proust and Flaubert became the diagnosticians of society. Both feel the pain of this society all the more intensely from a distance and write the findings in the upper-class homes of their claustrophobia. they withdraw. In the case of Marcel Proust, there is the writing bed in which he is cared for in his final years by the perfect substitute mother, the completely selfless housekeeper Céleste Albaret.

The death of his mother in 1905 did not really give Marcel Proust the freedom to live, but to write. With the gradual overcoming of the mourning phase, he descends further and further into the spheres of distanced observation. «In Search of Lost Time» is a reconstruction of places and years of life. Memory is the surrogate for the immediacy of lived moments, but it is also a powerhouse of displacements.

Proust describes an androgynous world, a world of matriarchal parts, which begins with concern for little Marcel in Combray and culminates in the figure of the Duchess of Guermantes. The model of the Duchess was the Comtesse Greffulhe. In the Third Republic, she filled the empty shell of the French high aristocracy with style show effects and played with the role of the female. Her remarkable family tree screamed: Family!

Mysterious unavailability

Marcel Proust stood on the sidelines like a shy waiter before he was presented to the Comtesse at a garden party at the age of twenty-one. With her veil she was an “enigma” for Proust. “J’aime les femmes mystérieuses”, the writer will confess after the encounter and later invent a whole series of women (and also young men) whose mysterious unavailability torments the narrator.

The Albertines, Gilbertes and Andrées of “Recherche” are creatures of an erotic and typological ambiguity that could only really come to life when the mother, worried about her son’s sleep, stopped sneaking very quietly through the apartment. Is it that simple with Proust’s mother, with this female superego? Maybe, maybe not.

There is an arc in «In Search of Lost Time». The story of a paradise lost in childhood. The drama about a mother’s refusal to kiss her goodnight continues with the adult narrator’s erotic attempts. It’s a failure of kisses. The addressed mouth, which in desire should be touched with one’s own mouth, is not reached. The lover’s head turns away, seems to evaporate. The crescendo of the sentences increases over the pages into a paper frenzy. Marcel Proust and his drum roll for what always remains just a goodnight kiss: “I’m finally kissing Albertine’s cheek.”

News from and about Marcel Proust

- Marcel Proust: The fibrillation of the heart. In Search of Lost Time. The original version. Translated from the French by Stefan Zweifel. Verlag The other library, Berlin 2022. 732 pages, CHF 55.90. – At the beginning of April 1913, Proust received the first printed sheets of his monumental novel, which at the time was still entitled “The Flickering Heart” (“Les intermittences du cœur”). Instead of simply correcting mistakes, Proust rewrote the book by hand on the proofs, giving it its later title. In this edition, the original version and the final version are to be read in parallel.

- Marcel Proust: The seventy-five leaves and other manuscripts from the estate. Edited by Nathalie Mauriac Dyer. Translated from the French by Andrea Spingler and Jürgen Ritte. Suhrkamp-Verlag (to be published in January 2023). – These are the lost earliest records of the «Research». They were found in the estate of Proust researcher and publisher Bernard de Fallois in 2018 and were published by Gallimard in 2021.

- Roland Barthes: Proust. essays and notes. Edited by Bernard Comment. Translated from the French by Horst Brühmann and Bernd Schwibs. Suhrkamp-Verlag, Berlin 2022. 343 pages, CHF 39.90.

- Andreas Isenschmid: The elephant in the room. Proust and the Jewish. Hanser-Verlag, Munich 2022. 240 pages, CHF 39.90.

- Luzius Keller: The Marcel Proust Alphabet. Friedenauer Presse, Berlin 2022. 1366 pages, CHF 96.90.