Zurich once issued epidemic passports to make it easier for the residents of the city-republic to travel. The local historian Peter Surbeck from Uster discovered one example.

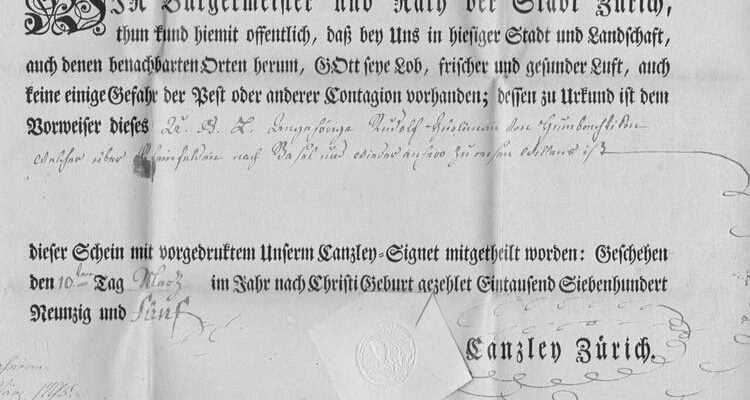

On a preprinted form with handwritten name and date, the Zurich authorities certified that the region was free from plague and other epidemics.

Why Rudolf Hürlimann wanted to travel from Hombrechtikon to Basel in 1795 remains a secret. What is clear, however, is that the Zurich law firm certified him on March 10th that the air in the city, in the country and in the neighboring towns is “fresh and healthy”. There is no danger of the plague or other epidemics – «God be praise», it says in an official document with a pre-printed Kanzlei logo.

Otto Sigg: “A remarkable automation”

Peter Surbeck recently found a copy of the epidemic passport in the depths of his computer. The former secondary school teacher is an honorary citizen of the city of Uster. The profound connoisseur of local cultural assets was honored for his commitment to monument preservation. He is now 86 years old. The calligraphically beautifully designed official certificate including the artistic first letter, which is anything but prosaic compared to today’s Covid certificate, he probably found many years ago in an estate or in a community archive.

The Zurich State Archives also suspect that. But that cannot be said with certainty, writes the customer service on request. There are very diverse collections on the subject of the plague. The health certificate from the 1790s is just one example. Unfortunately, it cannot be found in the relevant directories and cannot be further embedded.

Original sources are also not available to the former Zurich state archivist Otto Sigg. But what he can say with certainty: Due to a council resolution, the form was printed blank for the entire 1790s – probably in a few hundred copies. But why did the Zurich authorities offer a certificate at a time when the great waves of plague in Europe, above all the devastating outbreak in Marseille in 1720, had long since subsided? And the cholera pandemic wasn’t an issue yet?

According to Sigg, at the end of the 18th century there was actually no specific epidemic in either Europe or the Swiss Confederation. “But the fear of epidemic and endemic diseases was still great. For decades, even centuries, one had to fear infection when traveling. The host countries were also afraid of the new arrivals. “

In order to alleviate this fear and, above all, to make travel easier for the manufacturers of the textile industry, which was important at the time, in the entire city republic, including the Zurich region, all residents could have a health pass filled out, according to Sigg. “It is a remarkable automation and rationalization of the state administration for the time,” the former state archivist notes. In his opinion, the pre-affixed office seal and the empty date field were anything but common for the entire 1790s. “In times of constant epidemics, it was all about a quick travel certificate.”

Rheinfelden was abroad

The empty forms were probably deposited in the offices of the Land and Upper Bailiffs and were therefore relatively easy to use and fill out. Here – according to the handwritten entry – “To our gracious relatives, Rudolf Hürlimann von Hombrechtikon, who is willing to travel via Rheinfelden to Basel and back to Anhero”, this form was issued. Would said gracious relative of the Lord have been turned away at the Basel border without an epidemic passport?

Sigg also has an answer to this question: At that time the guards at the gates of the cities of Basel and Zurich would have checked the poor, vagrants and strangers, but did not deny them access to the official charity offices. Even without the epidemic pass, Rudolf Hürlimann would probably not have been turned away at the city gates of Basel, says Sigg. Nevertheless, the person entering the country could not have done without the document.

Because the certificate expressly states that Hürlimann traveled to Basel via Rheinfelden. Rheinfelden belonged to Upper Austria until 1803, so the village was located abroad for the Confederation. “The epidemic pass was at least useful, if not even necessary depending on the situation,” says Sigg. The historian and author cannot say what kind of identity card Hürlimann might have been carrying. As far as he knew, the canton of Zurich only introduced ID cards and passports with a modern look around 1810.

Strict guidelines because of the plague in Marseille

Unlike in the 1790s, Zurich had imposed strict measures in the early 18th century. The trigger was the great outbreak of the plague in Marseille, which claimed around 50,000 victims. On August 19, 1720, the Zurich city clerk’s office published a decree that the pastors had to read from all pulpits. The document can be found in the State Archives, the local historian Ulrich Brandenberger from Weiach researched it and commented on it on his community blog.

The regulations included smoking out letters and parcels from “suspicious locations” and checking all incoming goods and people. If the travelers could prove that they were in quarantine in a “healthy and unsuspicious place”, they were not turned away. However, a health certificate and documentation of the entire route were mandatory.