Researchers agree that deep circulation in the Atlantic will weaken. But if you ask them whether there are already signs of it, a lively debate sets in.

The fact that ice floes only float off Spitsbergen at certain times of the year is partly due to the deep circulation in the Atlantic, which brings warmth.

Svalbard is north of the 74th parallel, high up in the Arctic. Those who live there must be able to deal with the polar night and polar bears.

And with ice floes. But despite its northerly location, the sea only freezes over in winter, otherwise it remains ice-free. The cause of this is a huge ocean current. Researchers are discussing this more intensively than any other. The debate that has been going on for decades has only recently taken a new turn.

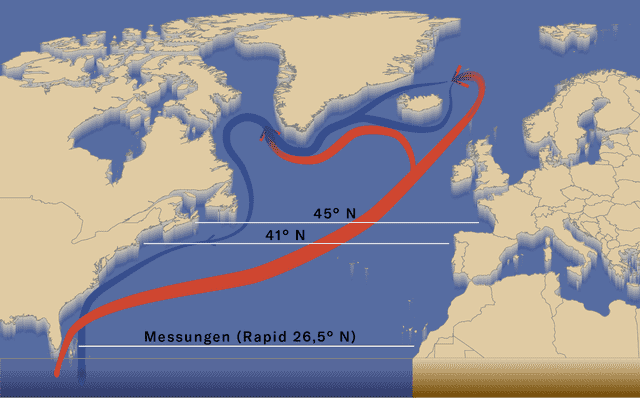

In this way, huge amounts of heat from the tropics reach subpolar and polar latitudes. Part of this current system is the Gulf Stream. However, scientists refer to the overall system as the Atlantic overturning or deep circulation.

Researchers have warned for many years that climate change could significantly weaken this deep circulation in the future. Because when temperatures rise, glaciers shrink and precipitation in the North Atlantic increases, seawater becomes warmer and less salty. This makes the water lighter and lighter, and this slows down sinking.

Due to the weakening of the current, the region around the North Atlantic would warm up less than other regions. That sounds good at first. But the alleviating effect would come at a high price: the climatic consequences, such as changed air currents and precipitation, would be felt all over the world.

Further consequences would also include a particularly sharp rise in sea levels in the North Atlantic. In addition, researchers are concerned that the deep circulation might not be able to recover afterwards – that the change would therefore be irreversible.

An invisible current below

But how unstable is this deep circulation anyway? And has the decline already started? While it sometimes seems like scientists already know the answers, answering these important questions remains a huge challenge. Researchers use measuring instruments as well as tiny marine organisms and supercomputers.

The latest contribution to the discussion on overturning circulation came recently from a team led by Laura Jackson from the Met Office in Exeter, UK. These researchers attempted to summarize in an article what the scientific community knows about the measurements of the circulation.

From 1980 to the mid-1990s, the deep circulation increased, after which it weakened again, they reported in the science magazine “Nature Reviews Earth & Environment”. They are firmly anticipating a weakening in the future. But so far they cannot detect such a trend in the data.

Old telephone cables measure the Gulf Stream

What makes it so difficult to spot trends in Atlantic circulation? Determining the movement of the water on the surface is relatively easy – whether with satellites, ships or measuring buoys. But the deep currents cannot be measured with satellites, explains oceanographer Arne Biastoch, one of the authors who works at the Geomar Helmholtz Center for Ocean Research in Kiel.

Long-term measurements of deep circulation have only been taken since 2004. “Rapid” is the name of this British-American program set up along the 26th parallel. The strength of the Gulf Stream off Florida is measured using old telephone cables, in which the movement of the water together with the earth’s magnetic field causes an electric current. There are also anchored measuring devices, for example near the Canary Islands, and measurements with ships. There are now also regular measurements at latitudes further north.

If the circulation in the Atlantic behaved like a sluggish river, the scientists would have no problems with the measurements. But unfortunately, as Biastoch explains, the flow is constantly changing, both spatially and temporally. It was only the Rapid program that revealed that the fluctuations were so strong. Incidentally, the researchers involved have to fight again and again to continue funding the groundbreaking measurements.

In order to find out more about current changes before the start of the Rapid program, researchers use ship measurements and weather data: They feed them into calculations with ocean models. Such deep circulation simulations even provide data for the last 60 years. However, they are considered less reliable than the rapid measurements.

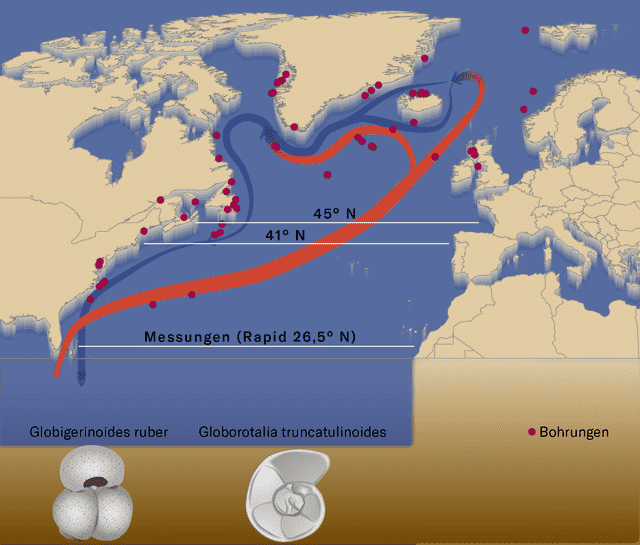

In addition, researchers are also trying to find out how the deep circulation has changed over the long term – since the 19th century, for example. Researchers evaluate geological finds for such reconstructions. In sediments they find, among other things, the sizeable limestone skeletons of tiny sea creatures, the so-called foraminifera.

These foraminifera live on the sea surface. Depending on the water temperature, the chemical properties of their calcareous skeletons differ. An analysis of the skeletons therefore provides information about the temperature at the water surface when the animals were alive – and thus also an approximate indication of the strength of the deep circulation.

A reconstruction carried out by a team led by Levke Caesar from Maynooth University in Ireland relied on such and other finds last year in the science magazine «Nature Geoscience» published. Accordingly, the deep circulation has weakened significantly since the 19th century. The current is weaker than it has been for over 1000 years.

Has the slowdown due to climate change started a long time ago and you just haven’t noticed it yet? Didn’t the measurements tell you? The answer to these questions is still pending. The flow reconstruction is a pioneering work and accordingly controversial. For example, it is very important which sediments are evaluated and which are not.

A group led by Halimeda Kilbourne from the University of Maryland recently reacted to Caesar’s study with some critical remarks. The researchers explained that only a subset of all those sediments that could provide evidence of deep circulation were evaluated in the study in «Nature Geosciences». Many other sediments have been omitted. The reasons were not clear to them. Because there are still many unanswered questions about this and other reconstructions, it is currently not possible to say with certainty how the current has changed in the past.

Provocative but valuable

Sedimentologist Samuel Toucanne of the Ifremer marine research institute in Brest, who does not belong to either research group, agrees with most of the conclusions of the Kilbourne group. He describes the study of Caesar as “provocative”. But she methodically advanced science. Further steps must now follow.

Oceanographer Gerard McCarthy of Maynooth University in Ireland is one of Caesar’s co-authors. Despite the criticism, he maintains his assessment that his group has examined evidence that allows solid conclusions to be drawn about the deep circulation of the Atlantic. Nevertheless, he considers the discussion initiated by Kilbourne to be valuable.

In contrast to Caesar’s reconstruction, calculations with ocean models for the 20th century usually do not show any long-term current weakening. This discrepancy is currently the biggest problem in research into the Atlantic deep circulation, says McCarthy.

Vortex of warm water

When it comes to interpreting the past, there are many differences. As far as the future is concerned, the researchers are still relatively unanimous: the Atlantic current will weaken. “There’s no doubt about it,” says Biastoch.

But one has to wait and see whether the system still has a few surprises in store. There are certainly processes that are not yet captured by observations and models. The current in the North Atlantic, like other currents in the world’s oceans, is “turbulent,” explains the oceanographer.

These eddies, often a kilometer deep and a hundred kilometers in diameter, carry large amounts of water and heat. If they slip through the meshes of the observation systems or models, this can falsify the results.

The accuracy of the ocean models continues to increase, says Biastoch. But this improvement also has a downside. The higher the spatial resolution of the computer models, the more the flow fluctuates in the simulations. If this corresponds to reality – so strong fluctuations are not unusual – then it will take even longer before scientists can identify a real, permanent decline in deep circulation.

Maybe climate change hasn’t actually weakened the current yet. But maybe it is.

The crux is: By the time it is finally clear what is correct, the change could already be irreversible.