Record amounts of cocaine are seized in Rotterdam every year. The customs investigators are stepping up their controls with scanners, sniffer dogs, divers and drones. But they can’t compete with the sheer crowd. The demand is too great.

Container terminal in the port of Rotterdam.

A shipping container, somewhere in the vastness of the port of Rotterdam. Inside: Nine young men, close to panic. Their metal shelter – twelve meters long, two and a half meters wide and partly loaded with tree trunks from South America – can no longer be opened. The door is firmly closed. The air is getting tight. They have no choice. You dial 121.

But where are they? The occupants cannot share their exact location. They only have a rough idea of where their container was parked. 911 only learns that nine people in a particular terminal are at risk of suffocation.

A short time later, helicopters are circling over the Maasvlakte, the westernmost tip of the port area. Police officers, firefighters and customs officials are combing the area with sniffer dogs. Your search is focused on a section of the ECT Delta terminals. After four hours they find what they are looking for. The young men survive. Only one of them has to be hospitalized because of breathing difficulties.

Men in metal boxes

How could the proverbial needle be found in a haystack? And what did the group have who turned themselves in to the authorities on September 13, 2021iet to look in the container at all? Ger Scheringa, the head of a special unit in the port of Rotterdam, cannot answer the first question for security reasons. On the other hand, you can learn a lot from the customs investigator about people hiding in large metal boxes.

“We call them extractors. These are people hired by criminal gangs to smuggle cocaine out of the port. Sometimes they travel to Europe themselves in the containers. Sometimes they sneak onto the docks and pick up the drugs. Or they first hide and then wait in the port until the delivery arrives.”

“Hotel containers” is the name of the phenomenon in which the extractors make themselves comfortable in their hiding places, often for many days. Again and again, the investigators find mattresses, sleeping bags, drinks, food and buckets in the containers that serve as toilets. Also tools to break open other containers or, if necessary, to free yourself from your own. But something must have gone terribly wrong in the action that kept half the port in suspense last year. Was the exit stuck? Was the container too close to another? “No comment,” says Scheringa.

We meet the gnarly customs officer in his office in Botlek. The sprawling industrial area is located in a middle section of the port, where there is little to see apart from chemical plants, oil tanks, freeway bridges and endlessly rushing freight trains. A minibus is parked in front of a gray box, and men in black diving suits get out of it. They are employees of «Hit and Run Cargo Team», in short: Harc.

“We are an amalgamation of customs, police, public prosecutor’s office and the financial investigation authority,” explains the man who is in charge here. “That gives us the clout we need to take action against organized crime. Because the drug problem is getting bigger every year.”

Mini submarines with drugs

Scheringa’s men seized exactly 7,575 kilograms of cocaine in 2014. In 2018 it was 18,947 kilograms, in 2020 it was already 40,641 kilograms. Last year, investigators seized 72,808 kilograms of white drugs with a sales value of more than five billion euros in the harbour. And it’s going on happily this year: Almost every week, the Dutch media report on cocaine finds, sometimes under a pile of wood, sometimes in banana crates, sometimes between frozen chicken meat or in drills.

More cocaine is now available in Europe than ever before. This is the European Monitoring Center for Drugs and Drug Addiction in their latest annual report Celebration. The EU agency sees the increasingly “innovative methods” of the smuggler groups “to supply the European market” as the reason for this.

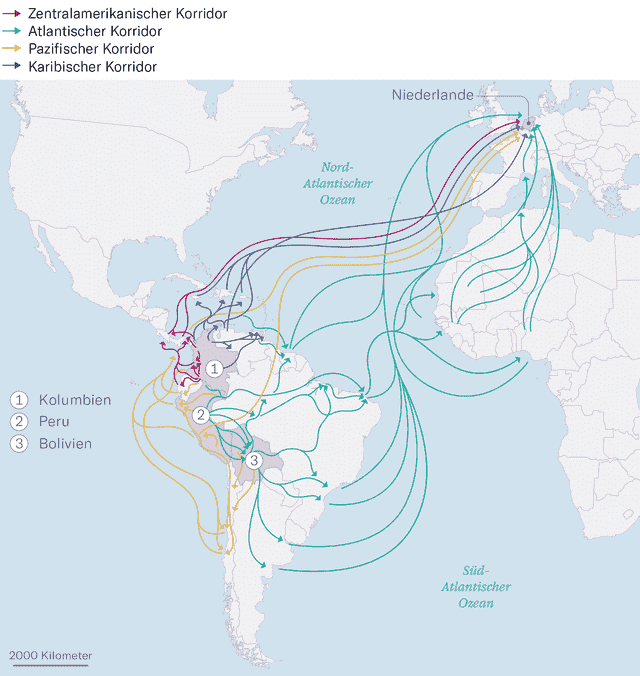

Above all, however, production in South America has increased enormously in recent years. Alone in Colombia Europol estimates that 2000 tons are produced annually. More than 60 percent of these are to reach Europe. Above all via the ports of Rotterdam and Antwerp in neighboring Belgium, but also via Spain.

How does the Harc team deal with the invaders? “Every day we check well over a hundred containers with the X-ray scanner or with sniffer dogs,” explains Scheringa. “We use risk analyzes to determine beforehand which containers are selected for the random samples.”

The country of origin and the type of cargo play a role in these risk analyses. Banana deliveries from Panama or Costa Rica, for example, are considered suspicious. But with a container turnover of 155 million tons per year it is impossible for the inspectors to check every single shipment. They know they only ever get their hands on a small portion of all imported drugs.

In addition, the drug is not only transported in containers, but sometimes in a part of the ship or even on the ship’s hull. For this case, divers inspect each cavity underwater. And drones are also used. However, the creativity of the smugglers knows no bounds, as has been known since the emergence of «narco submarines» white: These mini submarines, often made in the Colombian jungle and loaded with several tons of cocaine, cruise the Pacific coast and recently also the Atlantic. Investigators rarely catch them.

And money always lures

More smuggling, more trafficking, which also means more competition between rival gangs who want to profit from the lucrative drug trade. The murder of the prominent journalist Peter R. De Vries in July 2021 highlighted the violent nature of the “Mocro-Mafia”. De Vries advised a key witness in a major criminal case against the Moroccan mafia boss Ridouan Taghi and was probably shot in broad daylight in Amsterdam for that reason. The act caused pure horror among the Dutch.

“We got more money and more people after the attack,” says the head of the Harc team. “There was also political pressure. The Mayor of Rotterdam wanted that all incoming fruit deliveries from South America are checked.» That was unrealistic because the financial damage for the company is high if the logistical processing of the containers comes to a standstill. However, since not even his superiors had any idea of the size of the port, Scheringa had a film made in which a drone flies for several minutes over a sea of containers. “It has impressed everyone so far,” he says.

The port’s greatest weakness is anyway the human factor, in other words: corruption. Because in order for the extractors to be able to “work” undisturbed in the port, they have to find insiders. And that doesn’t seem to be a problem, like two masked men in one Interview with Dutch investigative reporter Danny Ghosen reveal.

‘If you come here in the morning I guarantee you can snag a security pass. You just say to a worker: lend me your passport by tomorrow and you will earn 500 euros», one of the men in an interview. Access to the port area and important information from inside – customs officials, security guards, cleaning staff or forklift drivers are bribed for this. If the insiders refuse to cooperate, the gangs try to intimidate them: “The moment a customs officer says no, you threaten to harm his children. Then he’ll say yes very quickly.”

The criminals earn 2,000 euros for every kilo of cocaine they salvage from the containers. If they are not caught in the act, they usually only risk a small fine for trespassing and possibly a prison sentence if they do it again. “The port is a gold mine,” enthuses one of the men interviewed.

It’s no wonder that the smuggler gangs in Rotterdam don’t have to worry about offspring. Just 13 years old was the latest suspect arrested by port police a few months ago. The criminals almost always come from the social hotspots in the south of the city. There, in the low-income neighborhoods of Bospolder-Tussendijken and Feijenoord, the extractors are recruited on the street, in sports clubs and even in schools.

40,000 lines of cocaine a day

Hugo Hillenaar, the Attorney General of Rotterdam, knows the stories of the young would-be gangsters: “When you see your friends with expensive things, there is a great temptation to quickly earn a few thousand euros. But once you’re in this drug world, you can’t get out of it.” It is not uncommon for little helpers to become cold-blooded criminals over time who are willing to kill people for money.

Hillenaar believes it is up to parents, schools and social workers to build resilience in young people. He wants more investigators for the Harc team and he wants the workers at the docks to learn more about how to protect themselves against the gangs’ attempts to lure them. But the prosecutor also reminds of the simple truth of supply and demand. “Every day, 40,000 lines of lines are snorted in the city of Rotterdam alone,” he says. “White Christmas” is what they call this in Europe’s largest port city.

But how are the authorities supposed to get the problem under control if demand doesn’t dry up and cocaine continues to make so much money that neither stricter controls nor stricter laws deter the gangs? Belgian criminologist Steven Debbaut from Ghent University considers the fight against drugs to be an “impossible fight”. That’s why you have to fundamentally rethink the way you deal with intoxicants in order to take the basis out of the cartels, according to Debbaut. Gradual legalization and regulation of the drug is the first step.

Of course, even in the liberal Netherlands, where there has long been a policy of tolerance towards soft drugs, very few want to go that far. Hillenaar, the prosecutor, trusts to inflict ever greater damage on the smugglers and thus disrupt the entire trade. Scheringa agrees. “I get up every morning to confiscate and destroy drugs. And I love my job.”

The Brussels correspondent Daniel Steinvorth Twitter follow.